“Malcolm Still Speaks.” Ibram X. Kendi on George Breitman and the Enduring Legacy of Malcolm X

From the Introduction to "Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements"

Forty years after assassins tried to stop Malcolm X from speaking, I arrived in Philadelphia for graduate school at Temple University. In 2005, this predominantly white campus sat in the middle of one of the largest Black urban communities in the United States. Affectionately called “North Philly.”

Malcolm arrived in North Philly in March 1954. I was twenty-three years old on arrival, Malcolm was twenty-eight—two years removed from being paroled from prison as an eager follower of Elijah Muhammad.

Malcolm had been incarcerated for six years, after being convicted of robbing houses around Boston and dating a white woman; after holding down low-wage jobs and illegal hustles up and down the east coast; after moving east from Michigan at fifteen years old in 1941; after being alienated from school; after a white teacher said his aspiration to be a lawyer was “no realistic goal for a nigger”; after shuffling between foster families and detention homes in Michigan; after losing his mother to an insane asylum; after welfare officials connived to break up his impoverished family rather than support them; after raging and misbehaving from hunger-burning poverty; after losing his father to a streetcar accident he thought was a lynching; after white terrorists firebombed his family farm following their move to Michigan; after watching his parents speak and preach about the Black power and Black pride of Marcus Garvey; after gun-toting Klansmen threatened his Garveyite family months before he was born on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska.

All these harms of racism still scarring him, Malcolm had orders from Elijah Muhammad to organize Temple No. 12 in Philadelphia in 1954. It was his last organizing stop before Muhammad sent Malcolm to where he wanted to be: Harlem’s Temple No. 7. Before North Philly, Malcolm had organized Temple No. 11 in Boston. Before Boston, Malcolm had exploded the membership rolls of the Nation of Islam’s Temple No. 1 in Detroit.

Paroled to his eldest brother’s home in Detroit in 1952, Malcolm immediately went out fishing for new recruits for Muhammad’s Nation. Malcolm believed that Muhammad’s teachings saved him from rotting away in prison; saved him from assimilationist ideas of wanting to be white; saved him from ignorance of Black history and humanity. He wanted Muhammad’s teaching to save every single Black person.

Every night after his job at a furniture store, Malcolm hit the streets. He spoke on behalf of the “Honorable Elijah Muhammad,” who quickly noticed Malcolm’s zeal. Muhammad saw a future minister. He likely encouraged the minister of Temple No. 1 to let Malcolm speak to the small congregation.

The squealing of pigs from the slaughterhouse could be heard nearby. But Malcolm likely did not hear the pigs. Only his nerves. Only his excitement. Malcolm went on to become one of the greatest orators in history. He spoke before thousands all over the United States, Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. But no speech compared to this first one in 1953. He addressed less than one hundred people.

Malcolm was ready to speak. All those debating matches in prison had prepared his voice. All that reading in prison had prepared his mind. “My brothers and sisters, our white slavemaster’s Christian religion has taught us black people here in the wilderness of North America that we will sprout wings when we die and fly up into the sky where God will have for us a special place called heaven. This is white man’s Christian religion used to brainwash us black people!” Malcolm proclaimed.

And while we are doing all of that, for himself, this blue-eyed [white man] has twisted his Christianity, to keep his foot on our backs . . . to keep our eyes fixed on the piece in the sky and heaven in the hereafter…while he enjoys his heaven right here…on this earth…in this life.

*

I enrolled in Temple University’s African American Studies program, a mile from where Malcolm had lived in 1954. Our events attracted North Philly’s graying Pan-Africanists, Garveyites, and Black power activists. They had high expectations for speakers. They expected speakers to make it plain and profound and powerful like Malcolm had done. When students and professors did not, let’s just say it was not pretty.

Some of these graying activists had their Malcolm stories. Some of them shared their stories in a course I took on Malcolm X, taught by Muhammad Ahmad, who Malcolm knew as Max Stanford, a founder of the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM). Graying activists almost always talked about some speech Malcolm gave in North Philly. Or somewhere else.

How Malcolm spoke to the most impoverished Black people as effortlessly as he spoke to the most elite college students. How he could start or stop an urban rebellion against racism with a speech. Speeches that rocked churches. Rocked streets. Rocked minds. Rocked bodies. Rocked every part of his listeners.

I started hearing these personal stories about Malcom’s oratory around the time I really started hearing Malcolm X for the first time. During my first year of graduate school, I was a hermit. I hadn’t been much of a reader in high school and college. My graduate school professors and classmates kept mentioning books I had not read. I kept jotting down the titles of those books and reading them. I spent every waking hour reading, catching up, kind of like Malcolm’s round-the-clock reading in prison.

During holidays, or sometimes on weekends, I visited my family and friends in Manassas, Virginia. I normally drove those two and a half hours from North Philly to Northern Virginia, spending the entire time on highways, literally and figuratively, listening to recordings of Malcolm’s speeches.

The more I heard his speeches over and over again, the more I could guess when he gave each one. Not just because I began to track the stages of his ideological evolution: from separatist to nationalist to revolutionary. Like most speakers, Malcolm got better and better at his craft over time. He worked at his craft religiously. All those late nights in his office attic listening to recordings of his speeches. All those adjustments to the index cards he used to outline his speeches. All that listening intently to crowds before he spoke each word. All that learning to “teach in terms that the people could understand,” as he once said. All that speaking to everyday people in private to learn the terms that they understand.

I graduated from listening to reading Malcolm’s speeches. I still remember the day I stole my father’s first edition copy of Malcolm X Speaks. Probably during Thanksgiving in 2005. The book came out in 1965, months after Malcolm’s death, from Merit Publishers, a Trotskyist imprint that became part of Pathfinder Press—and later it came out in paperback from Grove Press.

The more his ideas expanded away from Muhammad’s ideas, the more everyday people from the United States to Uganda seemed to gravitate to Malcolm.Dad’s forty-year-old copy was falling apart. Forcing me to read the book with care. Read it slowly. Take in every word. Stop to reflect. Keep the pages together as I kept his ideas together. And what I could not do as easily when listening to his speeches: go back and forth between speeches when I saw ideological connections or ruptures—or evolution.

After listening to his speeches, reading Malcolm X Speaks proved another experience entirely. No collection better shows Malcolm’s brilliance as a speaker. No collection better shows the evolution— and the initial summit of that evolution—better than this volume of Malcolm’s speeches, which mostly span from his leaving the Nation of Islam in March 1964 until his death less than a year later.

Malcolm is speaking no longer bound by Muhammad’s theology, or Muhammad’s reticence for revolutionary political organizing. “The Honorable Elijah Muhammad teaches us” had become the honorifics Malcolm was teaching to Black people in the last year of his life. Self-respect. Self-defense. Self-determination. Not merely for thy self. But for the Black world, for Black people to come together to gain control of their own political, economic, and spiritual destiny.

When a representative from the publisher visited Malcolm weeks before his death to discuss the idea for this book, Malcolm seemed intrigued. An unnamed associate accompanied Malcolm at this meeting. After Malcolm’s death, the publisher felt Malcolm speaking through these pages needed to be published more than ever. Malcolm’s associate helped the publisher gather recordings of his speeches.

The publisher brought on George Breitman to assist. As the book neared completion, Malcolm’s associate reportedly left the project, leaving Breitman as the sole editor of this book. Breitman was the founding member of the Socialist Workers Party and for a time edited the party’s newspaper, The Militant.

Malcolm spent many hours during the final year of his life traveling throughout Africa and talking to socialist revolutionaries who led their nations’ decolonial struggles, like Ghana President Kwame Nkrumah, Guinea President Sékou Touré, and Tanzania President Julius Nyerere. The more Malcolm spoke out against capitalism—”you show me a capitalist, and I’ll show you a bloodsucker”—the more socialists gravitated to him.

His ideas about colonialism, racism, Islam, white people, gender, Pan-Africanism, human rights, and power were changing and evolving too. The more his ideas expanded away from Muhammad’s ideas, the more everyday people from the United States to Uganda seemed to gravitate to Malcolm.

Everyday people like George Breitman. Malcolm’s “speaking style was…direct like an arrow, devoid of flowery trimming,” Breitman said in 1965, weeks after Malcolm’s death.

He used metaphors and figures of speech that were…rooted in the ordinary, daily experience of his audiences….He reached right into their minds and hearts without wasting a word; and he never tried to flatter them. Despite an extraordinary ability to move and arouse his listeners, his main appeal was to reason, not emotion.

Breitman was like you and me. Like almost everyone. He had no personal relationship with Malcolm. He never met Malcolm. Never heard him speak in person. Just wanted us to read Malcolm speak. Five assassins murdered Malcolm to stop him from speaking in 1965.

At the time, it was to silence his knowledge of Elijah Muhammad’s out-of-wedlock babies with former secretaries. It was to silence his avowals before the world that the United States was violating the human rights of Black Americans. It was to silence his relentless prosecution of American racism, of global white supremacy. It was to silence his exhilarating calls for Black unity. So our ancestors and our children would never hear Malcolm’s irrefutable case against racist power.

So I would never hear his antiracist words on those highways in 2005. So you would never read Malcolm speaking for human rights, right now. Through this volume, Malcolm still speaks. Read Malcolm speak.

______________________________

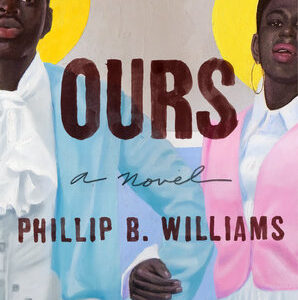

Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements edited by George Breitman and introduced by Ibram X. Kendi is available via Grove.