Malcolm Garcia Documents the Lives of America's Have-Nots

A Conversation with the No-Nonsense Journalist Who Goes

Beyond the Mainstream News

Popular magazines are the editor’s medium. Literary journals and books are the writer’s medium.

For this reason, I can safely predict that Malcolm Garcia’s work will never appear in the New Yorker. Malcolm does not submit to formula. This isn’t from any sense of literary arrogance. It’s in service to the people he writes about—Malcolm’s fealty is to their voices. There’s Jawad, a 16-year-old kid in Afghanistan who shines shoes to feed his family after his dad was killed; Dicky Joe Jackson, serving life in prison in Arkansas for selling drugs to pay medical expenses for his son; Billy McKenna who came home from the Iraq War, to later die from the toxins that spewed from open-air burn pits the US military operated to deal with garbage.

Malcolm moves through the world in a manner that Paul Bowles called a “traveler.” Malcolm has had legal mailing addresses but seldom lives at them. When I hear from Malcolm, the texts and emails are usually from places such as Afghanistan or Haiti.

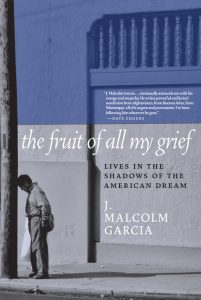

As we had the exchange for this conversation, Malcolm was at work in the Deep South, and his latest book was about to drop, The Fruit of All My Grief. I’d recently blurbed that book, which focuses on the United States. I wrote in part, “I urge [my] students to do what . . . Malcolm . . . does here so brilliantly: he listens to the voices of real people and then he channels their collective hopes and desires, their struggle against what John Steinbeck called the ‘marching phalanx’ arrayed against them. Others write about Wall Street. Then there’s Malcolm’s Street—the back alleys and shuttered storefronts of the inner city, the suburbs with their hidden desperation, the forgotten rural towns. In other words, the 99 percent of America.”

–Dale Maharidge

*

Dale Maharidge: When we first met in the 1980s, I was a newspaper journalist and you were a source. You were the director of the Tenderloin Self-Help Center, which served San Francisco’s homeless and mentally ill. I was amazed by your outreach efforts with that community: sex workers, people suffering from alcoholism and drug addiction, and veterans with PTSD. Tell a little bit about what you led you to that kind of work.

Malcolm Garcia: I have always been drawn to the struggle of people living on the street. As a kid living outside of Chicago, a high school friend and I would take the “El” into the city and hangout with the homeless alcoholics on south Michigan Avenue. It was an adventure for us. At the time I had horrible acne, almost boils, actually, and people would comment on it much to my embarrassment. What’s wrong with your face, things like that. But the men and women on south Michigan never said a word and I felt at ease no longer having to anticipate cruel, tactless questions about my acne.

After high school and college, bored, not sure what I wanted to do with my life, I traveled about the country, my Jack Kerouac phase, and worked a lot of shit jobs with people much older than me who assumed I had no more of a future than they did and they took me under their wing. It was like traveling to another country being with people who assumed they’d work ‘till they dropped and have little to show for it. I landed in San Francisco in 1983, stayed with a friend whose boyfriend became jealous of me and she put me out.

I then stayed in a homeless shelter and the shelter, after two months, hired me. My previous travels and my stay in the shelter made it a good fit. I was one with the “clients.” Yet I was not one of them. I could always call my parents to bail me out with cash if I chose. Aware of this difference, I began to recognize the gulf between the haves and have nots. I thought everyone should have the options I had, so I began telling people the stories the have-nots had told me, trying to convey that and how they were not the stereotyped “bums” as they were often portrayed in the media. This was the first step I see now towards writing about them.

DM: At some point you told me you wanted to apply to journalism school at UC Berkeley and I wrote you a recommendation letter. I then urged you to go work for newspapers, and you followed my advice. Sorry about that. I know you fought to get stories about real people in print at the Philadelphia Inquirer and later the Kansas City Star, which is where Ernest Hemingway once worked. Your editors were often less than receptive to your “street” stories. Hemingway might have had a fistfight with his editor if he’d been treated as you sometimes were.

Instead, you called your editor a “prison bitch” for Knight-Ridder, the chain that then owned the paper, as you pushed them to run a story about the disenfranchised. It seemed to be a real struggle. Not long after, you bailed on newspapers. This is a long way of asking: why do you think much of the mainstream media avoids writing about the vast majority of people who struggle to survive?

MG: The short answer is that the mainstream media sees no value in them unless they are part of some mass tragedy, a flood, mass shooting, etc. I was often told that readers in the suburbs would not care. The suburbs were our highest distribution area, so news was catered to what editors perceived as what they wanted to read. Corporate owned media chains are all about money. So, our corporate minders determined what was newsworthy. Poor people didn’t fit the findings of corporate focus groups.

For context about my transition from social services to journalism, about my third year in working with the homeless I developed a monthly publication I called By No Means, after the Jimmy Rogers tune, “I’m a man of means by no means / I’m king of the road.” I felt the mainstream media’s coverage of the homeless was cliché. They were pathetic during the holidays deserving only of condescending charity.

Outside of the holidays, they deserved our contempt and NIMBY laws. By No Means attempted to show them as real people. Influenced by Studs Terkel, the stories were all first person, but spliced together similar to lines in a play. I loved gathering stories for BNM. When I could no longer afford to publish it, I began looking into becoming a reporter with the intent of telling the same kinds of stories of marginalized people.

DM: Was that moment of leaving newspapers the birth of “Malcolm unchained?”

MG: The “unchaining” occurred while I was still a newspaper reporter. I started on the cop beat (4 p.m. to midnight) and, among other things, covered homicides. As reporters waited for the cops to talk to us at a murder scene, I’d hang with all the onlookers. They all had great stories about living in the inner city. My newspaper had no interest in these tales, so I wrote them up on my own time because I had a sense that I’d lose something of myself if I didn’t.

Often, I had no choice but to write a story the way an editor wanted. At home, I’d rewrite my way, again afraid I’d lose something of myself if I didn’t. I didn’t want to be compromised. I didn’t know exactly what I wanted, but I didn’t want to be compromised. I sent these two stories to one of my journalism professors who encouraged me to submit them to small press magazines.

DM: But you’ve paid a price. You may be one of the last “worker writers,” in the spirit of Jack Conroy. You’ve stacked Christmas trees for Home Depot and have done other manual laboring jobs to support trips to war zones and places struck by natural disaster. How has this helped your work, and, perhaps, hurt it?

MG: It helps because I never get too far away from the lives of the people I write about. It hurts because it takes time away from writing and can be discouraging. Of course, these are the same feelings had by the individuals I cover in my writing.

DM: The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle posits that the viewer alters reality of something he or she is observing merely by watching. One might contend that the observed also changes the observer. How has your work affected you?

MG: It has made me committed to doing my part to address the gulf between the haves and have-nots. It has made me committed to writing about the have-nots as three-dimensional people deserving of our respect, not contempt or pity. I suppose it has damaged my psyche seeing so much tragedy. Sometimes I get depressed. So far, I’ve had the privilege of being able to shake those moments off and write another story.

DM: Your journey from social worker to newspaperman to long-form literary journalist in hindsight seems foreordained to culminate in The Fruit of All My Grief, a melding of a blues song with angry grunge. How does this book fit in with the larger body of your work, past, present, and future?

MG: I’ve always written about people like those men and women depicted in Fruit. My war narratives have garnered more attention, but stories like those in Fruit were always at the heart of my urge to write. Fruit was and is a return to my roots. But the people in it have a lot in common with my war stories. Suffering and carrying on is at the heart of much of my work. So, Fruit is not a departure but a continuation of what interests me, the lives of people living below the news radar and their resolve to carry on in a world that holds them with little regard. It’s a rare courage deserving of our respect and emulation.

__________________________________

Malcolm Garcia’s The Fruit of All My Grief is available now from Seven Stories Press.

Dale Maharidge

Former newspaper reporter Dale Maharidge is a professor of journalism at Columbia University. He is the author of ten books, including Pulitzer Prize–winning And Their Children After Them, to be reissued by Seven Stories Press with new material in March 2020, and Homeland (both with Michael S. Williamson), as well as Bringing Mulligan Home: The Long Search for A Lost Marine.