Preposterous Tales

A review of Chicago: An Alternative History 1800-1900 by Professor Milton Winship, A. C. McClurg & Co., 1902, published in North American Review, June 1902.

*

The very title of Mr. Winship’s rambling, labyrinthine tome about Chicago in the nineteenth century hints at the confusion that lies in store for the unsuspecting reader. His opus, claims the author, is both “Alternative” and a “History.” An “Alternative,” one wonders, to what? Any attempt to compare Mr. Winship’s book with the work of serious historians who have addressed key periods of the century gone by would soon founder. For a text to be categorized as “history” implies, does it not, that attention has been paid to historical truth and accuracy? Anyone, then, who ignores facts or, even worse, blithely distorts facts for his own “Alternative” purposes has no right to attach the label of “History” to his offering.

To read Mr. Winship’s motley, meandering collection of half-truths, digressions and dilettante musings from beginning to end, is an endeavor I would not wish on anyone. I have worked through the long, dark nights on his typescript, only to prove the lie to that otherwise admirable proverb, “In all labor there is profit.” On this occasion, I regret to report that none is to be gained. Mr. Winship abjures the triumphs of our nobler forebears in favor of some whimsical tales about a cast of decidedly second-rate fellows.

Let me give an example that is fresh in your reviewer’s mind. I shall address the final chapter of the book. Proof, readers, that I persevered until the bitter end! And because I doubt few will cross that finishing line, perhaps I can offer you the following courtesy. I shall illustrate the duplicity of the author’s approach while relating, in more detail than you might want, how this maladroit volume staggers, huffing and puffing, toward its shabby, improbable end.

I should mention, in fairness to Mr. Winship, that he occasionally seems to remember that a book, like a building, needs a solid foundation. Whenever this notion reoccurs to him, he reverts to reflections about the land on which Chicago has been built. Hence, he starts at the beginning of the nineteenth century with the first of many a preposterous—to use his own word—tale. This one is about a mulatto trader involved in what Mr. Winship claims was the rst recorded land sale in Chicago. Not only does this lead him to the startling conclusion that this itinerant deserves to be called the founder of Chicago (the venerable Mr. Ogden must be turning in his grave), he also strays into banal reflections about a board game. He claims (I do not jest) that the destiny of Chicago would “hinge” on a game of chess.

We are treated to a stream of side stories that touch on real estate speculation, balloon houses, canal digging, railroads, sewage systems, agricultural machines, the timber trade, the Great Fire, the futures market, skyscrapers and the World’s Fair. And while attempting, in this haphazard way, to document how the empty swamps and prairies were peopled and exploited over our first century, he also pokes his nose into the city’s political, business and social affairs. He regularly chooses the wrong protagonists, thereby insulting our city’s true visionaries and heroes, and credits his bumbling cast with achievements they do not deserve. Apparently, it was mad John Wright who not only brought the railroads to Chicago, but also revolutionized American agriculture. And how Mr. Winship lavishes attention on the weaker sex, appropriating for them competencies and strengths far beyond their capabilities. In his fanciful picture of the city there are, can you believe, female photographers and female journalists. Worst of all, he insinuates that many of our leading businessmen and political leaders have been engaged in corrupt practices. Every city has the odd rotten apple. But why does Mr. Winship imply that Chicago has a barrel full?

Enough of the charges. Let me now provide the evidence. To do so, I shall refer simply to that final “Alternative” chapter, in which Mr. Winship excels in all the aforesaid techniques.

*

Students of Chicago history will know that the provision of clean water has bedeviled the city for decades. For most of the century, Lake Michigan was both the source of our drinking water and the repository for our waste, with predictably dire consequences. An engineer named Ellis S. Chesbrough tried to solve the problem, first by tunneling beneath the Lake and then by enlarging the first “canal” in a awed attempt to reverse the ow of the Chicago River. I am sure the poor man tried his best but simply got his sums wrong (a fact from which Mr. Winship chooses to distract us with one of his grubby asides about purported political corruption).

The magnificent new Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, built parallel to the original Chesbrough version, was officially opened on January 19, 1900, covering a distance of twenty-eight miles and connecting the Chicago and Des Plaines Rivers. As promised, it has permanently reversed the ow of the Chicago River, thereby ensuring that the city’s waste is no longer deposited in our Lake but, instead, flushed into the Mississippi and thence to the Gulf of Mexico. Readers will also recall with pride that the Canal is the largest and most advanced sanitary engineering project that has ever been constructed, anywhere in the world. They would therefore assume that an honest, responsible and patriotic historian would praise the Canal’s technical feats and record the extraordinary exertions and achievements of the characterful men behind it. How upset they will be to discover that Mr. Winship chooses to cover this triumphant moment in the annals of our city with a squalid little tale of intrigue about a buildings inspector, an alderman, a photographer and a journalist.

Mr. Winship’s version of events begins with an accident. In early December 1899, a buildings inspector slips and falls to his death off the top of a tenement block on West Sixtieth Street in the Eighteenth Ward while in the process of carrying out a safety inspection. The coroner records a verdict of accidental death and the case is closed. Some days later, though, the wife of the dead man makes contact with one of those female journalists on whom Mr. Winship dotes. “Mrs. Swanson,” he writes, “presented Mrs. Hunter with a photograph taken on the day of the accident.”

It was a Kodak snapshot that might have been taken in any of the West Side slums. Pictured was a large tenement building with windows either boarded up or open to the elements. The building was not, though, abandoned. At some of the open windows, there were faces staring out, apparently unaware that a photograph was being taken.

The snapshot showed that the building was being raised from three stories to six. Two figures were visible on the incomplete top floor. In the foreground stood a slender man, his hat pulled down low, who seemed to be writing in a notebook. That was Mr. Swanson, the buildings inspector. The other man was farther away, his image more grainy and indistinct. What made the photograph striking, what added tension to it, was the fact that—as Mrs. Swanson pointed out to Mrs. Hunter—the second man was in the process of throwing something at her husband. Moments after taking the photograph, she witnessed her husband fall to his death.

Mrs. Swanson alleged that it was no accident, but a case of murder. Her husband, she said, was experienced in working at heights. He had helped to build some of the most famous skyscrapers in Chicago, and it was only because the Depression forced him out of business that he was hired as an inspector. He would never have slipped of his own accord. The projectile must have struck her husband and knocked him over the edge.

Readers may be wondering, as was I, how on earth this incident could have any connection with the opening of the Canal. A tenuous link is established a few lines later, with a digression about a column Mrs. Hunter is preparing for the Chicago Daily Tribune. We are told this will not just be her final article of the year, but also of her career. With her sixtieth birthday in the offing, she has decided it is time to retire. The editor has requested that she use the column to make a series of predictions about the twentieth century. Mrs. Hunter, Mr. Winship is keen to point out, dislikes this task because she is a journalist for whom “facts have always been paramount.” That does not, though, spare us from hearing what those predictions are, affording Mr. Winship the opportunity to introduce Mrs. Hunter’s husband into the narrative. He is Mr. Tom Hunter, editor and contributor to an arcane literary magazine called The Dial.

No doubt, then, Mr. Hunter was behind some of the more fantastical ideas that would find their way into his wife’s column. These include skyscrapers standing one hundred floors high, trains traveling at more than a hundred miles an hour, the establishment of universal women’s suffrage, minimum wages of five dollars an hour, equal health care for all citizens and, believe it or not, the use of fingerprints to solve crimes. Finally, citing the Sanitary and Ship Canal, Mrs. Hunter predicts that the twentieth century will be an era of clean water for all. And so, in the nick of time, we are reminded that this is indeed supposed to be a chapter about the Canal.

Do not, though, be fooled into thinking that our arrival at that engineering wonder is imminent. You will have gathered by now that Mr. Winship does not write as the crow flies. First, we have to go back to the tenement building from which Mr. Swanson, the buildings inspector, fell to his death. Sadly, another tragedy is about to take place there. Over- night, on December 15, the building collapses. There are eighteen dead, fourteen wounded (details that have been corroborated by a variety of sources). According to Mr. Winship, Mrs. Hunter visits the site and is told that the building was being used as both accommodations and an illegal factory for about eighty recent immigrants, mostly Italian peas- ants and Russian Jews. When she hears that the building is said to belong to Alderman Oscar “Burner” Brody, she requests an urgent audience with the alderman in his office at City Hall.

Presumably because Mr. Winship believes it will help bolster his research credentials, he includes a copy of Mrs. Hunter’s private journal entry about that meeting. This hardly furthers his cause. She comes across as a bitter, vindictive woman; the kind of cynical modern reporter—and a female one at that—who, beset by feelings of her own inferiority, casts anyone who has attained a position of power and influence in the worst possible light.

[The following extract from Chicago: An Alternative History, 1800–1900 was NOT included in this book review but, in the interests of balance, we have chosen to quote it here in full.]

Burner Brody: Controls the Eighteenth Ward. Protégé of “King Mike” McDonald and J. Patrick O’Cloke. Associates with Boodler Johnny Powers (Nineteenth Ward), Hinky-Dink Kenna, Bathhouse John Coughlin (First Ward). Runs a protection racket, owns saloons, bagnios, tenement buildings, and an elevator. Often accused of running corners, but has always escaped charges. Drinks and gambles with the chief of police, plays golf with the mayor at the Lake Forest Club. Arranges jobs for men in his ward on the streetcars/building sites. Pays for Eighteenth Ward funerals and buys the flowers. Provides turkeys at Christmas. Keeps poorest constituents in coal over the winter (hence, “Burner”).

Called into the lion’s den, at last. The office is bright with electric lights. The carpet sinks beneath my heels. A stench of cigar smoke and whiskey. The walls are covered in photographs. Burner Brody is in every one of them. Also a massive larger-than-life portrait of him. Crude beyond belief. Reminds me of a giant hard-boiled egg propped up in an egg cup. Eyebrows are almost hairless, bald pate is oval-shaped, bloated florid cheeks, jowls swing smooth and low, and he has no neck.

The man himself is seated behind a desk the size of a billiards table, wedged into a dark green leather wing chair. He begins talking about the ghastly portrait. The reason he’s depicted wearing a green jacket with an emerald stickpin in his tie and a green sash over one shoulder is “in memory of my dear father and out of respect for his love of the Old Country. Forgive me my maudlin mood this afternoon, Mrs. Hunter,” he says, “but you will understand my grief at such an unforeseeable tragedy.” Was it really unforeseeable, I try to ask, given the poor state of the tenement building . . . ? But he does not let me finish.

He points to the portrait. “That baseball bat I’m holding,” he says, “was signed by Cap Anson. The greatest player the White Stockings ever had. Only twelve of those bats in the world, and I own every one of them. You do remember Cap Anson, don’t you? I’ll send you the book I wrote about him.” He’s written a book? I rather doubt it. I tell him not to bother sending it because I’m no baseball fan. “No, no, it will be my pleasure. And if it’s not to your taste, I’m sure your husband will like it. He’s a bookish man, I believe. Please sit down.” Why should he know who Tom is, and what he does? Don’t like that. Has he put Pinkertons on us?

As he drones on about the portrait, I notice that in real life he has a scar running like a worm from the edge of his left eye toward the top of the ear. An authentic touch for a thug. But the scar doesn’t feature in the picture. Obviously not a wound for which the alderman wants to be remembered in these days of respectability.

Not difficult to understand the appeal of his deep, husky voice and what a soothing effect it must have on a poor immigrant who only half understands what he’s saying. Everything will be all right, its tone seems to imply, as long as you do what I say. I will look after you, I will stand by your side through life’s twists and turns, I will find you work, I will bring you food if you’re desperate and coal in the winter when you’re cold. Just make sure you vote for me at the next election.

The flattery and lies begin. What a pleasure it is to meet one of the nest journalists of our age, a true child of Chicago and champion of the same just causes for which he has battled throughout his political life. “If only we could persuade our fellow citizens to believe as we do, that we must eliminate corruption and raise the daily pay of the working man to a fair level and clean up the levee and guarantee equality for all our sisters, we would be the greatest city in America, the greatest city in the world.” How excruciating.

“Let me tell you about my father.” I’d rather you didn’t, I think. “His story, and what happened last night, are closely connected.” Indeed? The logic escapes me, Alderman. “Do you know what my father had to do, when he first arrived in America? Dig a canal. Fifteen hours a day with his bare hands, at less than a dollar a day, fed on nothing but beans and grits, and forced to sleep in a leaking, mosquito-ridden pine-board shack.” He’s shouting at me now, as though it is my fault. “And why am I telling you this? Because Mochta Bruaideadh, God Bless Him, never lived to see the opening of the Canal he’d dug. And why? Because of an accident, an accident as unexpected and cruel as the one that brought down the building on West Sixtieth Street and robbed those poor people of their closest family and friends. The building in which my father died did not collapse. It caught on fire. That is why, in his honor, I have pledged that nobody in my ward will ever be short of coal in winter. You see why I’m telling you this, Mrs. Hunter?” Because you are trying to cover up what really happened. In your Old Country, Alderman, they’d call it a load of blarney. “I’m telling you because I want you to appreciate that I understand their pain. I have known that very same pain myself. When accidents happen, we must club together.”

He dabs his eyes with a pressed white handkerchief. “There was a poet from Great Blasket, whom my father revered, called Old Conn. And one of Old Conn’s sayings was this: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” The man’s insufferable. Even trying to pass off a common proverb as the wisdom of an old Irish poet. Now he’s smiling, as if all the bad news is out of the way. “I started out with nothing too, the same as my poor father. But I think you’ll agree I’ve made something of myself, Mrs. Hunter.”

I point out that for one man to die in a fire, tragic accident though it must have been, is hardly the same as eighteen innocents being crushed to death because an unsafe tenement building collapsed on top of them. His smile vanishes. “The building collapsed because it was illegally occupied by squatters, Mrs. Hunter.” Is he denying, I say, that those “squatters” were employed by him? He laughs. “What a ridiculous idea.”

I have another go. Mr. Swanson was a highly experienced builder who fell off the top of the very same unsafe tenement block he was investigating. Didn’t that make his so-called accident look suspicious?

No laughter this time. Brody bristles. Tells me to remember my place (i.e., as a woman) and to mind my tone of voice, or he will make sure I never have access to City Hall again. “Accidents are always happening in a big city,” he says. “It’s a fact of life.”

I try one last throw of the dice. Show him Mrs. Swanson’s snapshot and tell two white lies. First—the man in the background has been identified as Mr. Dermot O’Leary, his building contractor. Second—Mr. O’Leary has a brick in his hand that he is in the process of throwing at Mr. Swanson.

Brody claims it’s impossible to see anything clearly in the photograph, and I am wasting his time. “I am disappointed in you, Mrs. Hunter. Do come back if you have something serious to say.” I’m already at the door when he tosses out a warning, dressed up as another homily from Old Conn the Poet. “Neither luck nor good fortune ever came to anything that runs in people’s talk,” he says. “Do bear that in mind. Good day.”

I have the last word. Tell him I’ve checked the records. I know he’s the owner of that building.

By now, dear readers, you must feel mightily disoriented. I know I do. Why is Mr. Winship taking us on such an extensive detour? When will he remember we have journeyed to this remote and distant chapter because we want to celebrate the opening of the Sanitary and Ship Canal?

The story about the tenement building staggers on. In her Chicago Daily Tribune column the next day, Mrs. Hunter writes in a provocative fashion: “According to survivors interviewed by this reporter, the tenement building was used not only for accommodation but also as a factory for manufacturing items of clothing. Conditions were abysmal. There were no drains or replaces.” She alleges that just as Chicago has the right to be proud of its magnificent downtown skyscrapers, so too it should be deeply ashamed of buildings such as this one. Finally, she calls for the City Building Inspector’s Office to close off the site and to reopen its investigation. She demands an inquest into the tragedy. Those individuals found responsible, whether willfully or through negligence, should be tried before the chief justice.

The next day, we hear that a package is delivered at home to Mrs. Hunter. It contains a ceremonial baseball bat signed by the legendary Cap Anson, along with a copy of a book on baseball written by Alderman Brody. The book was not actually written by him, Mr. Winship hastens to point out, but was penned on his behalf. He includes a message that he says Mrs. Hunter found on the flyleaf, allegedly written by the alderman himself. Mrs. Hunter, have you forgotten what Old Conn the Poet says, about what runs in people’s talk? In baseball, if you don’t play by the rules, you can’t stay on the field. Take this as a worning.

*

Mr. Winship’s plot, I realize, is thickening, but to what end? And how much of what he reports as being “factual” can be verified? Shortly, we will consider this in more detail. Suffice to say that, regarding this particular incident, Mrs. Hunter was indeed found to be in possession of a Cap Anson baseball bat. But because no case would ever reach court, it has never been proven under oath how that baseball bat came into her possession or whether the misspelled flyleaf message is authentic or a fabrication by Mr. Winship.

The next thing we know, Mrs. Hunter has contrived to meet with Mr. Brody’s building contractor, his employee and boyhood friend, Der- mot O’Leary. I suppose one must concede that the lady is persistent. Mr. O’Leary is reluctant to speak out against his boss, which is what she desperately needs him to do so that she can build a story. Frustrated, she decides to fall back on an age-old reporter’s technique. Burner Brody, she says, has alleged that Mr. O’Leary has a professional history of cutting corners to save time and costs. “He has also identified you as the man in the photograph with a brick in your hand.” The article contain- ing these allegations, she tells him, will be published in the next day’s Tribune.

Mr. O’Leary, though visibly agitated, denies everything. Mrs. Hunter tells him she will postpone publication of the article for one day.

*

That evening, we are told, Mrs. Hunter discusses the story with her husband. He wants to know how far the “projectile”—brick or otherwise—was thrown. He points out that if it knocked Mr. Swanson over the edge, it must have been thrown hard and on target.

She shows him Mrs. Swanson’s snapshot.

“Maybe Burner Brody himself is the second man,” he suggests.

Mrs. Hunter says that is highly unlikely. She explains that when a buildings inspector carries out a visit, there is never any prior notification.

Not even the inspector knows where he is going until the last moment. So it would have been an extraordinary coincidence if Burner Brody had happened to be there.

“Unless he got a tip-off,” insists her husband.

“Even if he did, he’s hardly going to murder the inspector. He’s an alderman. If the report is negative, there are people he can talk to in the right places. He’s got time on his side.”

“Perhaps what happened had nothing to do with the inspection. Or, let me rephrase that, perhaps it had very little to do with it. Have you thought of that?” Mr. Hunter pushes his spectacles up his forehead. “Maybe they knew each other. Maybe there was an old grudge. And if it’s really not an accident and the alderman pushes the inspector over the edge, that means they must have a history.”

*

Do you see, dear readers, what has happened? Mr. Winship writes not only as if he is present in the house that evening with Mr. and Mrs. Hunter (he is not), he also pretends that he knows (he cannot possibly know) what they say. And the more we read, the more we find ourselves being drawn into this “Alternative” world where our author suddenly has the ability to read people’s minds and transcribe their conversations. It is not unlike participation in a séance, with Mr. Winship as our medium.

We must resist the lure of such narrative trickery and remember that this is no parlor game, but our living, breathing history. And what on earth has happened to the Canal?

*

Mr. O’Leary visits Mrs. Hunter the next day in her office. He looks haggard and, she decides, scared. Nothing like this has ever happened before, he tells her, even if it’s true that—always on the orders of the boss—he’s saved a few cents here and there. Nobody was ever killed, even if there had been the odd accident. This time he told the boss—no, he begged him—not to build that high without putting in more foundations. Nobody should have been allowed inside while they were working on it. An accident was inevitable. She had to believe him, that he tried to persuade the boss to let him make it safer, to put in the proper supports. “But Burner’s a miser and a bully,” complains O’Leary. “And he always makes me take the blame. Same with the elevator. You know I had to do a spell in Joliet once, so O’Cloke could get him off for fixing a corner?” And then he says, in a phrase that puzzles Mrs. Hunter: “He’s got the memory of an elephant, ain’t he, the boss? And Mr. Swanson, it’s true he was a feckin’ Scandi, ain’t it? Excuse the language.”

Before Mrs. Hunter can either question or caution him, Mr. O’Leary reaches into the bag at his shoulder and takes out a package, wrapped in brown paper and tied with string. He drops it on Mrs. Hunter’s desk. “He told me to burn it. But I didn’t.”

The next moment, he is gone.

Mrs. Hunter considers opening the package there and then. But she decides, on balance, it would be safer to take it home, away from prying eyes in the office. She goes by streetcar and, after alighting at her stop, begins to walk home. That is when she realizes she is being followed by two men in dark greatcoats and slouch hats. She stops and confronts them.

“We know everything about you, Mrs. Hunter,” says one of them. “That wasn’t a good idea, to meet with Mr. O’Leary behind the back of the boss. Don’t do it again.”

“Take a message to Mr. Brody,” says our doughty heroine (for we can all agree that this is what Mr. Winship has turned her into). “Tell him he won’t get away with this.”

“Is that all, Mrs. Hunter?”

“No, that is not all. Tell him that I don’t care what Old Conn said. I shall make d____d certain that what runs in people’s talk is the truth. Is that understood?”

The bravado, readers! Mrs. Hunter watches as her two would-be assailants stroll off along the macadam into the darkness, in boots that “clip the road like crackers.” Her legs, she then realizes, are trembling. She turns to go home, breaking into a run, to seek comfort from her husband.

She is so distraught, in fact, that she does not even remember to open the package given to her by Mr. O’Leary until the following morning. When she does, she finds a ceremonial baseball bat inside, smashed in two, signed by Cap Anson. The bat is stained with what she decides, in her wisdom, resembles dried blood.

In that afternoon’s Tribune, she sees a notice.

Man dies in streetcar incident

A man was run over by a streetcar at 5:13 p.m.

yesterday afternoon in an incident at the junction

of Clark and Kinzie Streets. The 56-year-old

gentleman was pronounced dead on arrival

at St. Isidore’s Hospital. He has been named as

Mr. Dermot O’Leary, resident in the 18th Ward.

Alderman Brody has expressed his condolences

to the surviving members of Mr. O’Leary’s family,

and has undertaken to provide owers at the funeral.

That same evening, Mrs. Hunter is working at home, finalizing the column for the Tribune on her predictions for the twentieth century, when a brick is thrown through her window. Tied around the brick is a message.

You’ll end up like him. No more wornings

A reviewer, however strongly he holds a point of view, must also have the manners to stand back on occasion and act as an impartial referee. By this stage in the narrative, when the reader is beginning to feel doubtful that the author can ever find his way back to those twenty-eight miles of canal, there is a welcome shift toward the light. The first sign that it may be forthcoming is to be found in the quantity of verifiable facts that have begun to impregnate the text. Even though these facts will only be confirmed to the ordinary reader at the very end, there would seem to be no harm done, for illustrative purposes, in mentioning them now.

Fact—Mrs. Hunter was indeed in possession of a “Cap Anson” baseball bat, broken in two.

Fact—Mr. O’Leary died in a streetcar accident, as indicated in the Chicago Daily Tribune notice.

Fact—Mrs. Hunter produced a receipt from a glazier, dated December 31, 1899, for the emergency replacement of a window at her home.

Fact—Burner Brody’s spelling can sometimes be erratic.

Fact—Sanitary and Ship Canal Trustees will be tipped off that the state of Missouri is preparing a court injunction to prevent the opening of the Canal, scheduled for January 19, 1900, claiming that the reversal of the Chicago River will pollute their own water supply.

Fact—To beat the injunction, a top secret private opening of the Sanitary and Ship Canal will be arranged for dawn on January 2, 1900, on the basis that the Canal, once it is open, will be impossible to close.

Fact—Mrs. Hunter will be one of only two reporters invited to the secret opening.

Before we attend that opening, there is one final stop to make. Mr. Winship insists that we return to the séance room and listen to more flights of fancy from Mr. Hunter.

“My guess,” he says, “is that Burner Brody gets a tip-off there’s going to be an inspection. He takes along one of his precious baseball bats as a gift to bribe the inspector. For Gus Swanson, this is just another day, another dangerous, illegal construction site he will have evacuated and sealed off before a tragedy occurs. He’s up there on the roof making notes for his report. Brody appears. Maybe they exchange a few words. Brody probably hails him: “Top of the morning to you, Inspector! How is your report coming along? Everything in order?” Perhaps Swanson looks up and greets him, before returning to his notes. Maybe he doesn’t look up at all. The point is that Brody recognizes him, but Swanson doesn’t recognize Brody. And that merely exacerbates the problem.

Whatever happened between them in the past was so unimportant to Swanson that he’s forgotten about it. Being on the receiving end of something is always more memorable, though, isn’t it? Brody doesn’t just remember, the memory makes him absolutely furious, so furious that he picks up a brick or a hammer or . . .”

Mrs. Hunter shakes her head. “Nobody holds a grudge that deeply,” she says. “And nobody in his position would act so impulsively.”

“Not unless he’s a psychopath.” End of séance. Curtain falls.

*

Good news, patient reader. We have negotiated the maze of Mr. Winship’s concluding chapter and arrived at “a little-known, little-visited, section of the Sanitary and Ship Canal in South Chicago on the bitterly cold winter morning of January 2, 1900. It is beginning to get light. About a dozen men, doing their best to keep warm, are gathered around an upturned hand cart whereon stands Mr. Wenter, president of the Board of Trustees of the Sanitary and Ship Canal.” From this cart, claims Mr. Winship, Mr. Wenter is delivering exactly the same speech that he would make two weeks later at the official opening to thousands of grateful, cheering citizens.

“This is the most important day in the history of Chicago,” declares Mr. Wenter, “the most important day since the land was first settled in what is now the last century.” [laughter] “We have built the finest city in America, gentlemen. Over 1.5 million citizens now live where, one hundred years ago, there were none. We are second in size only to New York. We are more than twice as big as St. Louis.” [cheers and applause] “The Sanitary and Ship Canal is an engineering marvel. It is the largest excavation project ever undertaken by mankind. It will reverse the Chicago River. Welcome, gentlemen, to a new age of fresh air, of clean water, of good health.”

The speech continues for some time in this vein. “When Mr. Wenter’s stock of rousing adjectives and adverbs has been exhausted,” reports Mr. Winship, “he approaches the flimsy dam that holds apart the waters of the Chicago River and the new Canal. He raises his hat, a signal for the two men at the base of the dam to light their fuses and scramble back up their ladders to safety. Mr. Wenter hurls a bottle at the dam wall that, ominously, fails to break on impact. The fuses below fizzle about like skittish cigarette butts until the powder catches. Blast follows blast, clouds of smoke billow forth and the odor of gunpowder fills the air, temporarily overwhelming the putrid stink of the river. They wait expectantly for the sound of sighing timber and the rush of breaking waters.

“To no avail. When the smoke clears, the dam becomes all too visible again, scalded here and there, but otherwise very much as it stood before. “There is no more gunpowder. Everyone is bitterly cold and wants to go home. Nobody knows what to do next. The injunction from Missouri to prevent the opening could be delivered at any moment. This is the situation that prevails when, to Mrs. Hunter’s surprise and unease, Alderman Burner Brody appears. She neither knew he was there nor that he had any involvement with the Canal. The alderman mounts the upturned handcart. He raises his hands for quiet. ‘Gentlemen, gentlemen,’ he calls out. ‘Fellow trustees. Your attention, please.’”

*

Mr. Winship’s unwieldy epic is drawing to a close. I said I would go to the bitter end in this review but, on reflection, I fail to see the purpose it would serve. What happens after Alderman Brody mounts the handcart, as related by Mr. Winship, has never been proven in a court of law. Dear readers, you have been warned. You venture into the final pages at your own risk.

Instead, I ask you to step back from the brink and consider the slant of Mr. Winship’s presentation. Mr. Wenter is making the magnificent speech that would be heard by thousands and reported across the world at the official opening a couple of weeks later. But what is Mr. Winship’s setting for its delivery? An upturned handcart, a frozen audience of a dozen (albeit a distinguished dozen), a dull and ordinary section of the Canal, an unsociable time of day, a screen of secrecy, a failed attempt to blow up the dam. In a word, ignominy.

Having plowed my way through the thousand-odd pages of this “Alternative History,” I am wise by now to the authorial techniques at work, so this damp squib of an ending to the century comes as no surprise. Mr. Winship has a tendency to shy away from celebrating civic achievements and, as soon as a situation arises that is soured by unanticipated setbacks, however minor and inconsequential, he stands ready to exploit them.

Everything in this account, therefore, must be treated with a large dose of salt. His only source for what happened at the secret opening is his favorite female journalist—Mrs. Hunter. Mr. Winship is doubtless an intelligent man who is fond of Chicago. Why, then, does he not unreservedly applaud the remarkable triumph of engineering and mastery over Nature that the Sanitary and Ship Canal represents? Why not bring our extraordinary first century to a close with the gay crowds, the flags and brass bands and ticker tape parades of those joyous celebrations staged on January 19, 1900? Would that not have been the proper thing to do?

Is it asking too much, to tell the truth? Is it beyond him to furnish future generations of Americans with the historical record they deserve?

Instead, Mr. Winship chooses to direct our attention away from that large, colorful canvas and take us into yet another of his little cul-de-sacs of intrigue, populated by the minor characters he prefers, spiced up with the kind of séance talk that has no place in a serious work of history. I rest my case.

Let me just say this. If we entrust our past to the likes of Mr. Winship, we shall never know the truth about anything. And that is not only intolerable, it is also, like so many of the tales in his “Alternative History,” quite preposterous.

Readers, I urge you to avoid this book.

__________________________________

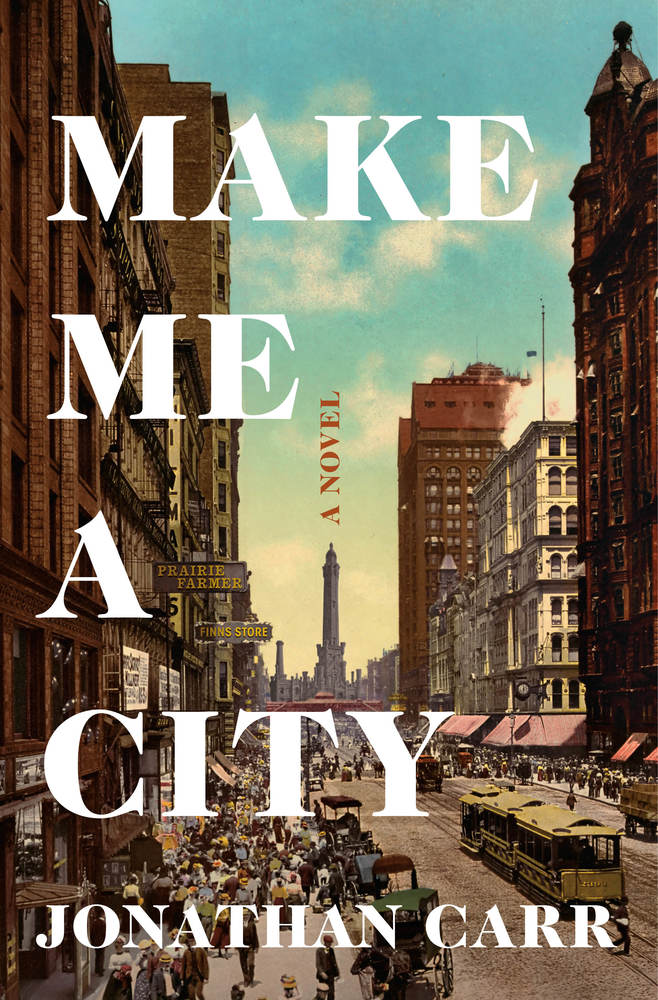

Excerpted from Make Me a City by Jonathan Carr, published by Henry Holt and Company March 19th 2019. Published in the UK by Scribe Publications UK and in Australia by Scribe Publications. Copyright © 2019 by Jonathan Carr Ltd. All rights reserved.