Maggie Smith on the Anxious, Silent First Year of Motherhood

“What had I done, insisting on more of us?”

The year after we got married, my husband started law school. As I saw it, we took turns supporting one another, each working while the other was in graduate school. Most like an arch.

On a cold afternoon in December 2008, mercifully after law school finals, our daughter, Violet, was born. She was three days late and right on her own time. I was scheduled to be induced the night before, and I’d been told they didn’t let you eat during labor (ice chips!?), so my plan was to fill up on some of my favorite foods before going to the hospital. I’d be prepared. We went to a diner called the Tip Top for lunch, where I had a pot roast sandwich on a pretzel roll—I wasn’t yet a vegetarian—and a side of sweet potato fries. What happened next is why, to this day, I refer to the Tip Top’s famous pot roast sandwich as “The Water Breaker.” No, the menu hasn’t been changed to reflect this.

I suspected I was leaking—just slightly—but there was no rush of water like in the movies. I felt fine. Maybe it was nothing, I thought. I was convinced that if we called the OB, the midwife on call would tell me to stay home until my contractions began. I’d probably still be able to have dinner at home! My heart was set on a specific burrito from the prepared section of Whole Foods (I know, right), so we headed there next.

Did I rush home to pack my hospital bag? No, I stood in the checkout line in wet underwear.

I was standing near the salad bar, holding my coveted Brazilian shrimp burrito, when I felt it: whoosh. Water. I couldn’t deny it this time. Did I put the burrito back and walk out? Did I rush home to pack my hospital bag? No, I stood in the checkout line in wet underwear. I’d heard about the hours and hours of ice chips and Jell-O cups in the maternity ward. I would be prepared. With protein.

I turned to my husband as we left: “Can we stop by Half Price to get a crossword book on the way home? In case I’m bored at the hospital?”

Wanting to stop at a bookstore in wet underwear was taking it too far. He drove me home, and I called the OB’s office. When I described what had happened, they told me to go straight to the hospital. But my induction wasn’t until 7:00 that night! It was only midafternoon! I hadn’t even packed my bag yet! None of this mattered. So I threw what I thought I would need into a duffel bag—pajamas, robe, socks and underwear, toothbrush and toothpaste, face wash and contact solution, and a mix CD I’d made with Welcome, Pickle! written on the disc in Sharpie. (Pickle is what we’d been calling the baby, since seeing the first blobby ultrasound.)

At the hospital they started me on Pitocin, since I wasn’t yet contracting. Contraction feels inadequate to describe what was happening inside me, but during labor all language was inadequate. I had never felt pain that exquisite before, and I haven’t since, at least not physically. That pain, so deep inside, deep and beyond reach, made me want to jump out a plate glass window. I was in labor for 24 hours—stubbornly trying new positions and pushing like hell—before I accepted that the baby wasn’t budging and begrudgingly agreed to a Caesarean section.

When they finally held her up, showing her to us over the surgical drape, I said, as if I recognized her from someplace, “Violet!” We’d had a short list of names for boys and for girls, but when I saw her, I knew her name. I knew her.

*

It was the middle of winter in Ohio, bleak and washed out and bitterly cold. I would sigh a small round circle into the frosted windows, like a miniature porthole, and look out at the world I no longer felt I belonged in or to. Postpartum depression broke over me like a colossal wave almost immediately after Violet was born, though I didn’t call it by its name, and I didn’t treat it. It’s hard to treat what you can’t—or won’t—name.

The land of poems felt impossibly far away.

My husband was in his last year of law school; I was on maternity leave from my job as an editor for an educational publisher. Each day I watched the clock, waiting on edge for him to come home. How fiercely I clung to him then. How primal my love for him, how palpable my need. What had we done? We had been happy. What had I done, insisting on more of us?

We were renting a large three-bedroom Victorian house in German Village, a historic neighborhood of Columbus known for its brick streets, horse hitching posts, gas lamps, and manicured gardens. Our house was built in the late 1800s. Each day I did our laundry in a cramped cellar with low ceilings and a dirt floor. There were so many burp cloths and bibs crusty and sour with spit-up, so many unmatched socks the size of my thumb, so many pairs of footed pajamas, so many receiving blankets. Bags of labeled breastmilk in the freezer. Naps scheduled and hoped for, desperately hoped for, and missed. Outgoing mail I had no stamps for.

Outside the trees were encased in ice, the branches clacking against each other. What spark was I supposed to feel each day in waking up, tipping the whistling kettle over the coffee grounds, warm and wet and black as soil, then trudging, hunched over, to the basement to do more laundry? What spark was I supposed to feel in making a bottle, then another bottle, then another bottle? How sad the kettle sounded when I removed it from the flame—how it whined before it grew quiet, went silent.

I didn’t write for the first year of Violet’s life. Strike that: I couldn’t write. I was sleep deprived and anxious and, I know now, suffering from something with a name. Something I could have treated. The land of poems felt impossibly far away; I could barely make it out on the horizon and had no idea how to get there. Even if I’d known the way, even if I’d had a map, when could I have made that journey?

After a year, the first poem finally arrived.

__________________________________

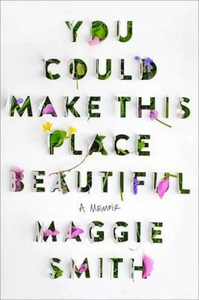

From You Could Make This Place Beautiful. Reprinted by arrangement with Atria/One Signal Publishers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2023 by Maggie Smith.

Maggie Smith

Maggie Smith is the award-winning New York Times bestselling author of eight books of poetry and prose, including You Could Make This Place Beautiful, Good Bones, Goldenrod, Keep Moving, and My Thoughts Have Wings. A 2011 recipient of a Creative Writing Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, Smith has also received a Pushcart Prize, and numerous grants and awards from the Academy of American Poets, the Sustainable Arts Foundation, the Ohio Arts Council, the Greater Columbus Arts Council, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She has been widely published, appearing in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The Nation, The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Best American Poetry, and more. You can follow her on social media @MaggieSmithPoet.