Lynn Steger Strong on the Importance of Imaginative Truth in Fiction and Nonfiction

“The goal is not to tell the reader the facts as they happened, but to, hopefully, bring a bunch of sentences and paragraphs to imagistic life.”

Thomas Bernhard’s biographer claimed that he masturbated in front of the mirror. True or not, it’s a great image. Bernhard wrote what might, at first glance, feel like the same thing over and over—what might, lord help us all, be referred to as autofiction—misanthropic ranting men, purportedly like him. Most have lung diseases; Bernhard almost died of a lung disease. He got so sick he was given last rites, he supposedly said that he survived to spite the doctors, whom he thought of as not very smart.

He wrote about musicians, writers, geniuses, and losers, ambition, suicide, the hypocrisy of Austrian society, friendship, and art. But the content of a Bernhard novel is never the point. Like most great books, his are about the experience you have when you’re of inside them: the way the sentences build on one another, repeat and circle through and churn inside ideas, the way they exhaust and then revive, thrill and overwhelm, frustrate, consternate, and delight.

Like the music he studied when he still had the lungs be an opera singer, like an Ad Reinhardt or Agnes Martin painting, his work forces you to get inside it, to sit and look and listen, only to refuse clear explanations, only to rebuff your need to climb out of it with a concrete idea of what exactly has been done to you while you were there.

Neither the art nor the facts tell us who the person was, exactly…but the art gives us clearer, more thrilling access to the truths.

Bernhard wrote a five-volume auto?biography that is beautiful but not particularly revealing. Like many biographies, the more details you learn, the further from the person you can sometimes feel. Think of googling a first date just before you meet them: so much information, age, job, birthplace, moved from Atlanta to LA when they were fourteen, captain of the high school soccer team. But does it prepare you, really, for the way they lean in too close, talk only about themselves, and their breath smells inexplicably like meat? I love artist biographies, but when they’re not great, I hate them just as quickly. I’m fascinated by artists’ lives, but often once I finish, I feel that much surer that the facts don’t come close to telling me the particularities of who this person was.

Of course, it’s story that does it—and the best biographers know this. Neither the art nor the facts tell us who the person was, exactly—I’m not sure that’s possible—but the art gives us clearer, more thrilling access to the truths—the feelings and the ideas that churned most constantly inside them, the things that kept them up at night.

Imaginative truth is a term I use a lot in teaching and what I mean is the ineffable, murky, and miasmic that does not (could not) ever fit inside of any individual biographical fact. Even that image of Bernhard masturbating: it might not be true, it might be something he did once, it might have been a joke he told that someone passed along to someone else and then someone else decided to declare as fact.

The word imagination comes from the word image, something conjured. In fiction, through image and sensation, we help the reader see, touch, and feel, and in so doing the ideas we want them to move through stick in a more affecting and engaging way inside their heads. Whether or not Bernhard ever stood and pleasured himself in front of a mirror is not relevant to the work that image might do to evoke a feeling: to make an idea legible is so much of how fiction works.

Degas said, “Art is not what you see but what you make others see.” Baldwin said, “All I know is you have to make the reader see it”; from Cheever, “fiction is meant to illuminate, to explode, refresh”; and Stephen Millhauser, “We walk through a world continually disappearing from view. One thing fiction does is restore the hidden and vanishing world. It makes the blind see.” Rilke wrote, “Is it possible, it thinks, that we have neither seen nor perceived nor said anything real or of any importance yet? Is it possible that we have had thousands of years to look, ponder and record, and that we have let those thousands of years pass like a break at school, when one eats a sandwich and an apple?” And Lorrie Moore, “One has to imagine, one has to create (exaggerate, lie, fabricate from whole cloth, and patch together from remnants) or the thing will not come alive as art.”

So often, we move through life bombarded by facts but wholly incapable of knowing how or why they add up to what we think or feel about a given situation, way of being, person. What fiction can do is make the unseen, misunderstood, and too easily (mis)presented become straightforward and clear, more legible and palatable, while also letting it be messier and more complex.

What fiction can do is make the unseen, misunderstood, and too easily (mis)presented become straightforward and clear, more legible and palatable, while also letting it be messier and more complex.

Fiction writers snatch at and invent image, scene, dialogue, and object. Sometimes we snatch at life and sometimes we invent it. In both cases, the goal is not to tell the reader the facts as they happened, but to, hopefully, bring a bunch of sentences and paragraphs to imagistic life, to help the reader see the world anew.

A fun exercise when you’re starting (or in the middle of) a novel: Pick a premise that is generally accepted that you both basically understand why people buy it but also fundamentally believe is bullshit. For example, writing from life is not imaginative. Now, build out some objects to complicate this idea. (And here I apologize in advance, but you might need to install a character who is also a writer) Then what if you took the reins away from her? What if—because you think writing fiction is dangerous and also, that it should be fun—you throw in a gun.

Think about a question that you’re fascinated by but can’t quite get hold of: what is imagination and why does it suddenly feel so valuable to you? Force imagination to then be an act not just on your novel but inside of it: All novels are constructions, there is no such thing as a reliable narrator. Embed that fact in the novel by letting your narrator acknowledge she’s making it all up. That she is wantonly and recklessly imagining her way into other people. Because that is what all fiction writing is.

Give the characters more siblings to remind the reader that every act of memory is also inherently constructed and imaginative, informed by feelings, impulses, and failings that few of us will ever wholly comprehend. While the facts might sometimes be wrong, in watching people conjure different versions of the exact same stretch of time, we might see not only their points of disagreement and the tensions between them, but also the moments of overlap that might bring them back to loving one another after all.

Make, in other words (and this is from Ted Chiang) all the various ideas you’re most interested in “storyable.” Again, through imagination, the conjuring and enacting of image both from little bits of life but also from thin air. Construct scene, dialogue, memory, objects, a sense of time and place in which the reader might be fully immersed, and then, once they’re in there, try to flip and switch and complicate their sense not only of fiction, of what it is and can be, but also of what it is to be alive.

__________________________________

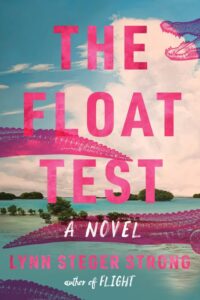

The Float Test by Lynn Steger Strong is available from Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Lynn Steger Strong

Lynn Steger Strong is the author of two novels, Hold Still, and Want. Her nonfiction has appeared in The Paris Review, Guernica, Catapult, LARB, and elsewhere. She teaches both fiction and nonfiction writing at Columbia University, Fairfield University, and the Pratt Institute.