Lydia Kiesling on Making the Lists—or Not

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Novelist and critic Lydia Kiesling joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss the creation and the spirit of year-end book lists. She talks about list culture getting its start at the small, online literary magazine, The Millions, and its eventual spread to seemingly every media outlet. The three grapple with the significance of inclusion on these lists, whether they really sell more books, and the ethics of their construction. Kiesling reads from her new novel, Mobility.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

V.V. Ganeshananthan: What does a good process for creating [year-end] lists look like? Because what I think basically happens when I start to imagine the process is, I imagine another version of me who has no other job but to read and reads much faster than I do. She reads like 1,000 books and then very carefully curates a selective, beautiful, diverse, and inclusive list of 100. How can taste-making of this kind be ethical? Is there a good way to do it?

Lydia Kiesling: I honestly don’t know. I liked what you said before about how it just seems more ethical and makes more sense when it’s tied to a person’s sensibility rather than an entity or an institution. There are lots of books that people really like and are acclaimed, and we’ve all had the experience when you read a book that people love, and then you’re like, “What? What is this? I hate this shit.” On the other hand, some book becomes a cult classic because it was completely slept on, and someone finds it, tweets it, and some magic happens.

So, I think part of the thing about the list—which you really pointed to—is that when people have not read the books, it’s so weird and creepy. It’s like, you’re reading the publisher’s description or someone’s tweet being like, “This seems like something someone would want to read.” It privileges people who’ve already published books because of name recognition, where it’s like, “Oh, if you love the title, then you will be excited to know that another book is coming out.”

For debut writers, it’s awful, because you’re just going on the publisher’s copy. And I think some of those are really the publishing shit shows that we’ve seen in recent history, where they’re striving for some sort of timeliness and importance. That can lead to some really weird judgments all around about what people imagine other people want to read and are looking for. It sucks because nobody has read the fucking books.

Whitney Terrell: Are you talking about the anticipation lists? Or are you also talking about the year-end lists?

LK: No, I’m sorry. I am not. I’ve completely derailed the topic.

WT: You’ve hijacked our topic about the end of the year lists. Hopefully people have read those books.

LK: You know what? I bet—because I’m an asshole—I bet that there are some books on some lists that have not been read.

WT: I’m sure that is true. I think that is a good point to make.

LK: But I would say it’s much more likely that they have been read, if they’re on the year-end lists.

VVG: Yeah, I guess I’m just imagining some newsroom where one person has read one book and not the other, and then the reverse is true of their well-respected and beloved colleague. And then they’re forced to have some sort of strange argument, kind of like horse trading, to decide which of our books gets to be on the list. “I read this one, and I read the other one, so we can’t actually compare.” Who’s going to win that argument?

LK: Someone should write a book about that.

VVG: We have to ask, of course, how useful are these lists? Are they genuine markers of what books were best in a year? Or are they markers of how good the author’s, editor’s or publicist’s contacts were at a particular institution? And maybe most importantly, do they actually help to sell books?

LK: I think they are definitely an indication of the skill and luck of publicity teams and sort of the connectedness of teams. I think that’s one thing that is true. I think it is also true that it’s the books that made an impression on the people who read them and sort of created buzz, which again, is often tied to the first piece. But, I do think they help sell books.

I think people buy books during the holidays more. I know bookstores are often saying a huge percentage of their annual business happens during the month of December. So, people are definitely buying books. I think those lists do help shape those purchases when you’re just like, “Okay, let me quickly visit this outlet that I normally would go to for culture coverage. Let me see what they have on there.”

I also think booksellers do a lot because the way that they put their books out, the books they have in the center facing outward, their little shelf talkers or whatever they’re called, have a huge impact. Booksellers are very influential, too, at the end of the year when people are making decisions about this.

WT: So, speaking about the skill of your publicity team, we wanted to talk to you because we like your novel, but also because your first novel, The Golden State, was published by MCD books, which is an imprint for Farrar, Straus & Giroux—an old line and traditional publisher. Mobility was published by Crooked Media Reads in partnership with Zando, which are both relatively new, and I think you were the first book published by Crooked Media Reads. They’re a company that puts out podcasts that are incredibly successful, but book publishing is new to them. What was that like? How did their publicists do? Did they have the kind of contacts that a place like Farrar, Straus & Giroux has?

LK: Zando was started by Molly Stern, who comes from traditional Big Five publishing, and all of the people that she hired for editorial and publicity, to my knowledge, also come from there. First, the reason that I went there is because Emily Bell, who was my editor for The Golden State, had gone there. So, she sort of lured me. That’s one thing, but Zando’s model is that they partner with influential people and institutions. It is essentially like an imprint model, which they have in Big Five publishing—it’s kind of like finding a person or an institution to put their name on, partner with, and have a list that matches their sensibility.

I knew that Emily Bell was there, and I had a great experience with her with The Golden State. I also had a great experience with FSG, generally no complaints there, but you feel attached to your editor in many cases. I will say, I felt apprehensive because she went to Zando a couple of years before Mobility was ready to take out, but she said, “I know you’re working on something. I really want to see it. I want to publish this book,” which was nice to know that she was still interested in my work. But, I was kind of like, what is this? Where are you? Then, when she did see the book, she was like, “I want to publish this no matter what. But one of our new imprint partners is Crooked Media.”

She made a very compelling case that they would be able to get a lot more eyeballs on the book, because I think that’s the ultimate issue with publishing—just figuring out what makes people buy books, what makes people hear about a book, what makes people interested in a book. Because Crooked does have this really strong built-in audience, and because I was guaranteed to have total editorial freedom, and it would be the same kind of process that I would have gone through at FSG editorially, I thought, okay.

Again, Emily was why I came, and the way the publicity part works is that Zando has its publicist and book marketers, who are amazing and all came from FSG. So, there’s a lot of crossover from traditional publishing with a lot of the same methods with their own sort of twist, and there was a lot of energy there because it was a new venture. So, I think there was a strong impetus to try and do really well for the books. And then they would work with Crooked’s marketing people on some kind of joint things and podcasting, so there were a lot of people who were thinking about it, definitely more than I would have had at any traditional publishing venue.

I was not someone who really listened to Pod Save America religiously, but I would hear from friends—who aren’t people I think of as being really up to date on what’s going on with literary fiction—and they’d say, “Oh my God, I just heard an ad for your book. I’m so excited.” And so, I was like, well, that is proof that people are hearing about it, who might not have otherwise because they don’t obsessively read the lists.

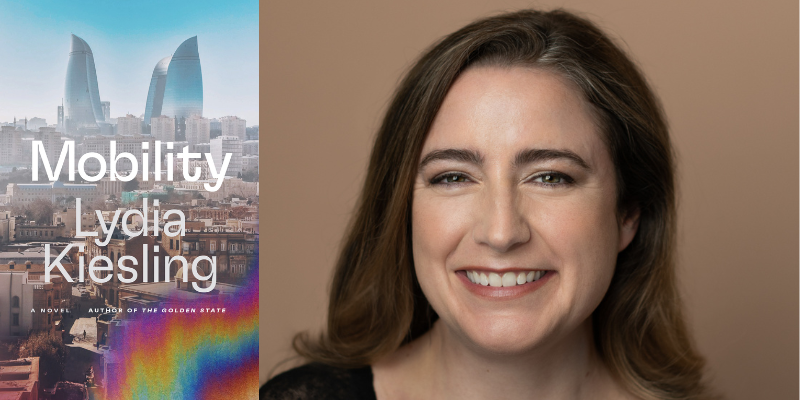

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Mikayla Vo. Photograph of Lydia Kiesling by Erica J. Mitchell.

*

Others:

Pod Save America • Books We Love | NPR • A Year in Reading: 2023 | The Millions • 100 Notable Books of 2023 | New York Times • The 10 Best Books Through Time | New York Times • A Year in Reading: 2023 | The Millions • “Crime,” by Marilyn Stasio, August 19, 2001| New York Times • “‘Terrorist’ – to Whom? V.V. Ganeshananthan’s novel ‘Brotherless Night’ reveals the moral nuances of violence, ever belied by black-an-white terminology” by Omar El Akkad, Jan. 1, 2023 | New York Times • Molly Stern • The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn • Bridget Jones’s Diary by Helen Fielding • The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan • Blink by Malcolm Gladwell • The Collected Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald • The Stand by Stephen King • A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley • The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver • Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry • The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan • Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy • Ali & Nino by Kurban Said • The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne • Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad • Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe • The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway • 1984 by George Orwell

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.