Luis Alberto Urrea on Family Stories and the Work of Witnessing

“We carry inside us a theater, a library, a storehouse of quotidian detail that becomes heroic and eternal by the force of our art.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

In Spanish, we have things we say that are different from the way Americans talk, or possibly even think. For example, a phrase for slightly absurd acts of chivalric ardor is “Una Quijotada.” You might say it’s “doing a Quijote.” Lovely and concise. I admit: I’m doing a Quijotada in my writing. Another slight departure from English rhetoric is the way Spanish requests your attention. Traditionally, we didn’t say “pay attention.” We said “presta atencion.” We asked you to lend it for a moment. Allow me to borrow your attention. You owe me nothing.

My family and friends often appear in my stories. I think yours appear in your stories as well, though often hidden. I try to reveal them whenever I can because this culture erased or ignored or insulted them. This isn’t a screed — as hard as it is for me to believe, some people don’t know much about, say, Tijuana, or small towns in Sinaloa. And, like Garcia Marquez, I have been blessed with exceptionally vivid relatives.

My family members are all contained in their own earth-bound solar systems, and they are suspicious of navigators who land on their shores. The riddle for me was, how can such giants as Tia Flaca, my godmother, my father, my cousin Rubio, my first crushes Quela and Fina, the women making tortillas in Colonia Independencia, become smaller and smaller as I set out to conquer the world? How does one take them on the journey? How does one find a telescope that makes them bigger as the distance grows? This turned into a project that had no name, but became the act of immortalization.

As Picasso once suggested (stealing from Da Vinci), art is a lie that illuminates the truth. So, behold Atomiko. One of my most popular characters. A mad cholo who homesteads the Tijuana municipal garbage dump and who fancies himself the greatest Samurai warrior in Tijuana. People still contact me to ask how I created that madness. Um, he was my cousin.

Here’s the thing, not all the things I say about him are true. But they’re accurate.

His name is Hugo, and he lives in what was once my grandmother’s house on out old dirt street. He never even visited the garbage dump. Hell raiser. Practical joker. His cousin on his father’s side is a gangster known as “The Man Who Burns Down Cities.” He once convinced my father that he had become a Mormon and put The Book in his glove compartment to take to me in San Diego. To convert me. But when I opened the glove box, the book actually was a photo encyclopedia of 1,000 African Sexual Positions.

There was no way to lose with such a literary character lounging in the basement of my own life. And now, he is the friend of thousands of readers.

Hugo watched American TV (long before cable or streaming—you just pointed your rabbit ears at San Diego). He liked PBS because they showed Samurai movies. He announced he would become Tijuana’s first Samurai/Ninja. And he did it! He trained himself. He even carried a Samurai sword in his truck so he could chase bad guys down the street. The Terror of Tijuana!

I have just pulled back the curtain: I would likely never write an essay about Hugo, but when I remembered these moments, I couldn’t stop laughing. There was no way to lose with such a literary character lounging in the basement of my own life. And now, he is the friend of thousands of readers.

The work of witness here would not have succeeded if I had simply transcribed his details into a story. First of all, they would not have been accurate. It is part of the strange magic of fiction that the myths and diversions we write can be truer than the truth. How so? I realized by accident that what I was after was the man’s myth about himself. The legend in which he was Toshiro Mifune. He was walking in some picaresque mock-heroic movie starring himself. I try to impart this to my workshops: find that personal myth of the person you know so well and bring it to life. That inner myth you know so well because you are a person of story. Conjure it, and urge it out of the shadows and make it eternal.

I was learning as I struggled to bear witness to my unseen, unheeded friends and family, that not all heroes were Steve McQueen.

The discipline in this art is not perforce in having writing skills, it is in remembering.

Now I have a WWII novel based on my mother’s exploits with the Red Cross. The entire novel came from hearing her nightmares every night, from her foot locker full of pictures, and the way she turned into Greta Garbo when she smoked and replied to any wit at all with a swoony, “Oh, Dahling….”

We carry inside us a theater, a library, a storehouse of quotidian detail that becomes heroic and eternal by the force of our art. For me, every character coaxed out of the shadows of what seems trivial brings my lost family to life, my disrespected border, my lonely beloveds. Not a biography, a celebration of their own personal mythos made visible. How they might wish to be known. And they will now outlast me. Friends, it’s a prayer.

_____________________________________

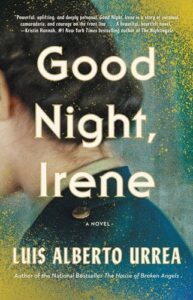

Good Night, Irene by Luis Alberto Urrea is available now via Little, Brown.

Luis Alberto Urrea

A finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for his landmark work of nonfiction The Devil’s Highway, now in its 30th paperback printing, Luis Alberto Urrea is the author of numerous other works of nonfiction, poetry, and fiction, including the national bestsellers The Hummingbird’s Daughter and The House of Broken Angels, a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist. A recipient of an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award, among many other honors, he lives outside Chicago and teaches at the University of Illinois Chicago. His latest book is Good Night, Irene.