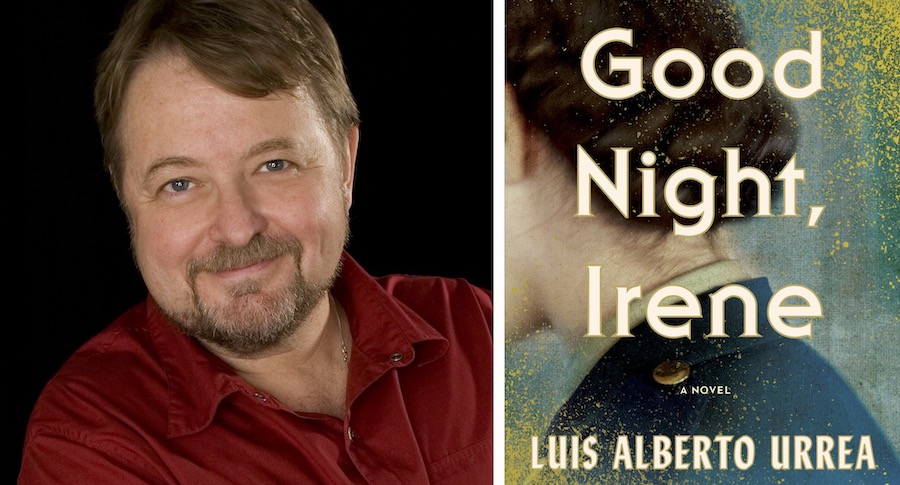

Luis Alberto Urrea on Creating Fiction From Family History

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of Good Night, Irene

Luis Alberto Urrea’s dramatic, heart-breaking new novel, Good Night, Irene, brings to light the heroic World War II service of a group of American women rarely written about. The novel was inspired by his mother, an East Coast WASP who served as a volunteer during World War II offering donuts and coffee to soldiers on the front lines. I asked him if he’dheard of “Donut Dollies” before reading his mother’s journals?

“I’d only ever heard the term from her. I only had the vaguest idea of what she did—like most of those who served in WWII, she didn’t talk much about it. She had a war chest she told me to never open; I was a kid, so of course I opened it the first chance I got. That forced her hand when I found photographs of Buchenwald inside among her memorabilia. I learned about Buchenwald before I ever learned about the Clubmobiles. She was reluctant to talk much about her own service, but she had many things to say about the wonderful soldiers and pilots and she always wanted to have a sentimental chat about General Patton.

Occasionally, she’d get nostalgic and tell me a bit about what she did and the terrible injuries she survived. But honestly, because she rather downplayed her own role, I think the whole ‘Donut Dollies’ thing didn’t make all that much of an impression on me. It was only years later, after my mom was gone, I was telling my wife about my mother and that she was in WWII. My wife just stared at me with her mouth open and kept saying, ‘What? WHAT?!’ I had thought everybody knew these stories and it never occurred to me that it was THE story.”

With his wife (a former newspaper journalist), Urrea went back through his mother’s journals and photo albums.

“We started poking around to see what we could find. It was shocking to find out there was so little information about the Clubmobile Corps and that these women are not a part of the historical record of the time. We read everything we could find, but it was only when we accidentally discovered that my mom’s best friend, the driver of her truck and the last surviving WWII Clubmobiler, was still alive and just 90 minutes from our house, that everything fell together.

We spent hours with Jill Pitts Knappenberger—94 when we found her and 102 when she passed in 2020—and just soaked up her stories and pored over her scrapbooks. That’s when my mother—and this book—came to life. I got to meet her, through Miss Jill’s eyes, at her very best. Miss Jill told me, ‘I drove the truck, but your mother brought the joy.’ Thanks to Miss Jill, this book was born at that very moment.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have these years of pandemic and tumult been for you? What was the progress of your new novel, Good Night, Irene, during this time—writing, editing, preparing to launch?

Luis Alberto Urrea: Between teaching and speaking engagements and research and travel, the writing life sometimes leaves precious little time for the actual writing. That’s why so many writers rely on residencies and retreats. But I am more of a homebody, so the pandemic ended up granting me my own writing retreat at home. It was glorious to have all that uninterrupted time (except for the occasional TV binge) to write and research and rewrite and think and garden a little bit. I completely refocused the book and the way I wanted to tell the story. Good Night, Irene is definitely my pandemic baby.

If you are trying to construct a kind of historical ritual, or in more artistic terms, a kind of symphony, there must be interludes and modulations.

JC: What inspired your title, the Lead Belly classic that also shows up as a theme song of sorts in your narrator Irene’s wartime experiences?

LAU: The main character was always going to be named Irene—it was my mother’s middle name. And I think it was all a bit of writing alchemy, right? That song was always in the background, but it wasn’t until the development of Handyman that the song became a refrain of sorts. Of course, it is a bit of Americana but I also wanted the Lead Belly version to be Handyman’s touchstone, his appreciation of *all* of America. He is an unlikely cowboy from Eastern Oregon who has a love for this blues singer. This to me is the best of America. It is my subtle nod to the undersung heroism of people of color. I am always going to be representative in what I write.

JC: It was shocking to read of the intensity of your Irene’s frontline experience. She was in London when the first bombs fell, served at a B-17 base, went into Utah beach, followed Patton across Western Europe, including into Buchenwald, was trapped in the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium, had a near fatal truck crash in the Bavarian Mountains. Reading Good Night, Irene, I was caught up in the dangers surrounding her. Did your mother experience all these wartime episodes? How were you able to re-create them? Through her journals? Talking with her best friend and driver Jill, the “living witness” you met when she was 94?

LAU: All of those things you mention are exactly what happened to my mother, in the exact order in which they happened. I tried to use the stories she shared as well as I remembered them. She told the buzz bomb story often. She spoke with great affection about the bomber base in Glatton and I had her photographs. She did not really talk about Utah Beach. She adored Patton and made me sit through the film three times in a row. We spoke of her experience at Buchenwald. And though she did not talk much about the Siege of Bastogne and the Battle of the Bulge, in another memoir, I found a detailed accounting she gave of being trapped behind enemy lines on Christmas Eve.

As soon as I read it, I knew it to be true: for my entire life, hearing the Christmas Carol “Oh, Holy Night” brought her to tears. She told me a bit about her accident and the tale of those who found her and what they said. The story of the burned soldiers was hers. And I can tell you this: two things terrified her in the war—the sounds of enemy army tanks in the darkness, and the nights spent cowering in barns as Russian troops raped women. I grew up with my mother’s physical pain and her scars. I also grew up with her psychological wounds, her nightmares woke me most nights.

I tried to use the primary source of my mother as much as possible. Jill helped fill in a lot of details. I matched up what they remembered with the recorded history as much as possible. And I read the memoirs of other Clubmobilers to make sure I was being as accurate as I could be.It was so important to me to get this right and I hope I did these women justice.

JC: What were the limits on the roles American women could play during World War II? Did you have a sense that your mother was frustrated by these limits? Were your narrator Irene and her friend Dorothy?

LAU: My mom didn’t discuss those sorts of things, but Jill certainly did. She joined the Clubmobile Corps because that was the only way for her to be up at the front, in the heart of the action. She often told us she was NOT going to sit around in the rear. She didn’t have time to train as a nurse and they wouldn’t let her actually fight. She wanted to be at the front. Her twin brother Jack was there and she wanted to make the same effort. It was Jill who wanted to drive the tank and I made sure to borrow that story for Dorothy.

Interestingly enough, in my research I discovered that the military was not eager to have it be known women were actually in the combat zones. There was a sense that maybe the folks at home wouldn’t think it was so bad if the “girls” were there, too.

I definitely wanted to make it clear that Dorothy was frustrated with what she saw as her limited role, whereas Irene was fully engaged in her service and couldn’t imagine more.

JC: How long did that program in the US military last? Why was it ended? And yes, they were heroes.

LAU: The Clubmobile Corps continued into the Vietnam War. However, it did not survive long in Viet Nam. The culture had definitely changed.

JC: In a time before anyone talked about PTSD, Irene and her Dorothy witnessed shocking wartime violence, brutality and mutilation, and had the frightful experience of visiting a concentration camp shortly after the U.S. military occupied that part of Germany. How did you go about configuring the aftermath of their experiences and the lack of medical attention so that narrative would stay within the realistic framework of the 1940s? What do you think would happen now to noncombatants put into these circumstances now? Or would they be?

LAU: Well, they did discuss it but it was known as battle fatigue or shell shock. Notoriously, many soldiers who were consumed by this phenomenon were considered malingerers or weaklings or even worse, as cowards. In Jill’s archives, there is a letter from a GI who got sent home with “shell shock.” He eloquently expressed his shame. I don’t believe Buchenwald, as terrible as it was, was what caused these responses in the women in my story. It didn’t help. But the basis for my own mother’s night terrors was the stress of being hunted and of seeing her friends annihilated and from constantly being in danger. It seems to create an almost mythological horror.

Neither my mother or Jill or any other woman in the Clubmobile Corps, and by extension none of the women in my novel, would EVER dare to claim “shell shock” or “battle fatigue” as a malady. They simply believed they had done their duty and they would not have ever felt entitled to something they would believe the soldiers had earned. After all, they were not the ones fighting.

Today, this would not happen. There would be therapy and groups and counseling. It is a different, more nuanced era. That being said, veterans continue to die at a terrifying rate from self-harm. We lost an acquaintance to that this week because of combat experience.

JC: What sort of geographic and archival research did you do in order to write these vivid scenes of wartime England, France, Belgium and Germany—to “travel the roads and locations visited by the crew of the ARC Clubmobile Cheyenne,” retracing your mother’s journey in this novel?

LAU: It began with my mother’s personal photos and scrapbooks and then everything we could find on the internet and in other archives. We went to the World War II museum in New Orleans and dug through military archives at the Smithsonian and every museum we could think of (Seattle, New York, Washington, DC). Then to Europe and multiple visits to museums in England and France.

We rented a car and drove all over Germany, trying to retrace as much of their journey as possible. We spent a long weekend in Weimar and many hours at Buchenwald and in its museum. A long-planned trip to the UK was delayed by the pandemic, but last summer we finally got to visit Glatton and the airbase and the cottage where she lived. But the most important “geographic research” was to drive the 90 miles to Miss Jill and dig through her astonishing scrapbooks and memories.

I created this whole scenario for these imaginary characters and after the fact, found out it was what happened, it was true.

JC: There are moments of R&R throughout the novel, in particular a shift from war duty to a week on the Riviera, at Cannes, where Irene meets up with The Handyman, a fighter pilot, who becomes her romantic partner. (“Trance of romance in France,” she writes in her journal.) How important was it to include these interludes in your narrative? In your introduction you say Handyman was a fictional character and yet….your mother’s wartime buddy shows you photographs of her at Cannes with a boyfriend Jake.

LAU: If you are trying to construct a kind of historical ritual, or in more artistic terms, a kind of symphony, there must be interludes and modulations, there must be moments of respite. It’s not all fire and explosions and terror. They were there to provide momentary sanctuary to the soldiers. They were due momentary sanctuary in honor of their bravery. The reader, as well, needs moments of joy and relief. Because it is a journey through a written composition with highs and lows, you try to place them in the right spots to motivate your partners (the readers) to go on.

The appearance of Jake was a surprise bit of magic for me. I had already created the Handyman and written the scenes in Cannes. The only thing I knew for sure about their visit to Cannes was some pictures of Jill and my mom lounging around with cocktails. The fabulous brakeless German car was a story my mom told me. That was all written when Jill opened her most special photo album and there was my mom on the Riviera in the embrace of a dark and mysterious handsome man in swim trunks. “Oh,’ Miss Jill said “That’s Jake.” “Who is JAKE?!” I cried out. Her response was classic: “It was a war. We all had men.”

Even more marvelous was being allowed to go through Miss Jill’s letters after she died, before they were all donated to an archive at the University of Illinois. The book was done at that point. But in that cache was a letter from a GI thanking Jill for her kindness to him and asking, by the way, whatever happened between Phyllis and that hot-shot pilot she was so crazy about?

It’s magic, right? I created this whole scenario for these imaginary characters and after the fact, found out it was what happened, it was true. I don’t know what it means, but somewhere my mom is giggling.

JC: Dorothy makes a friend of the Handyman’s buddy, Smitty. She joins in some of his clandestine sniper attacks on German soldiers. Which precipitates the novel’s dramatic and mysterious conclusion. Were women able to act in such maneuvers?

LAU: I have no idea. I just know this is something the fictional character of Dorothy did. Jill did not do anything like this, nor did my mother—or any other Clubmobile worker, as far as I know. It is complete fiction.

We did ask Miss Jill if it would be possible to smuggle a baby in the truck and she looked at me like I was crazy. “I guess you could,” she said. “But I don’t know why you would.” Fiction! Though the germ of this idea came from my mother’s story of a refugee asking them to take a child to safety. They could not. I wondered what might have happened if they had decided otherwise.

JC: What are you working on next? Writing another novel based on your mother’s experiences?

LAU: One and done. Though there is a long story/novella about Irene’s childhood experiences in Mattituck that never fit in the novel that may turn into something else.

I just published a new book of poetry, Piedra (Flower Song Press). And my next book is a return to the borderlands, a novel with some magical realism which, if you know the border or Mexico, is simply realism.

__________________________________

Good Night, Irene by Luis Alberto Urrea is available from Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.