When I was a child, my father taught me how to read handwriting. He left books by my bedside—The Art of Graphology, Handwriting Analysis: Putting It to Work For You—that I skimmed half-interested, looking mostly at the pictures. He showed me Emily Dickinson’s handwriting and informed me that its rightward slant meant she was emotionally expressive; the large spaces between words meant she had an outsized need for privacy and personal space.

“Look, she makes her Ds like you do,” he noticed, with the stem swinging to the left like a lower-case Greek Delta.

Later, I began to read the graphology books on my own. At a party once, when I was teenager, I made a dozen people write a sentence, put it in a hat and then attempted to match the handwriting with their respective owners. When I received a love letter—when people still hand-wrote letters—I’d be less interested in what was written than the slant of his or her writing, by my potential lover’s signature. I checked if the lower loops of the letters where rounded or triangular; if there was a wide space before my name; the slant and height of the lower case when they wrote the word love.

When I asked my father, an immigrant from the Philippines, why he was fascinated by the shapes of letters on the page, he told me that it had to do with the limits of language. “I wanted to understand the minds of my clients,” he answered. “I needed a way in, to get ahead.”

“The limits of language are the limits of my world,” wrote Ludwig Wittgenstein.

My father, an insurance agent, grew up at the foot of the Mayon volcano; he lived on a coconut plantation and first boarded an airplane after he was married, moving to a new continent with two suitcases and a young wife. The year he immigrated he worked manual labor in a paint factory; he wouldn’t set foot in Europe until his fifties.

He wanted to feel less disoriented. To get ahead.

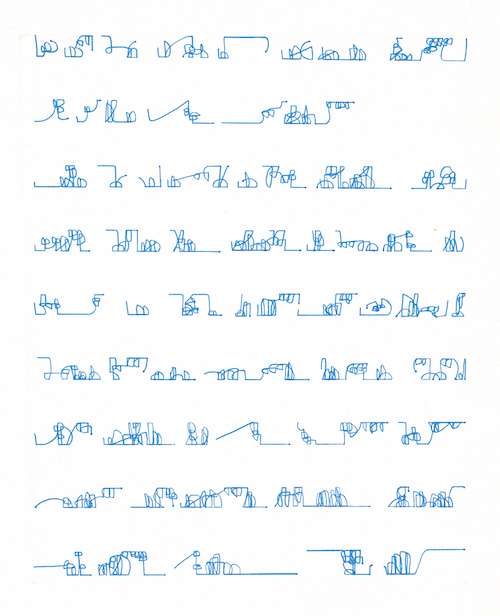

From ‘Sin título’ (Libro), 1971, unique artist’s book, ink on paper.

From ‘Sin título’ (Libro), 1971, unique artist’s book, ink on paper.

*

I was going to Berlin to feel less oriented. I wanted that vertigo that comes with flailing unassisted in a new language, from standing on a street corner and getting lost immediately. “Arriving at each new city, the traveler finds again a past of his that he did not know he had,” wrote Italo Calvino. “The foreignness of what you no longer are or no longer possess lies in wait for you in foreign, unpossessed places.”

I was in Berlin to write about my family history, about borders. I had a painful experience at border control; my anxiety about politics and my personal life had reached a breaking point. I decided to sequester myself in my friend’s unrenovated apartment near Hermannplatz, the site of a 1929 Communist uprising, commemorated in history books as Blutmai (the Blood May riots). I’d carry notebooks and turn off my mobile phone and wouldn’t ask for WiFi passwords. The onslaught of social media, the news, the language of tweets, was beginning to feel unbearable. I was coming to the conclusion that words were worthless, that meaning could, at any point, become muddled, lost.

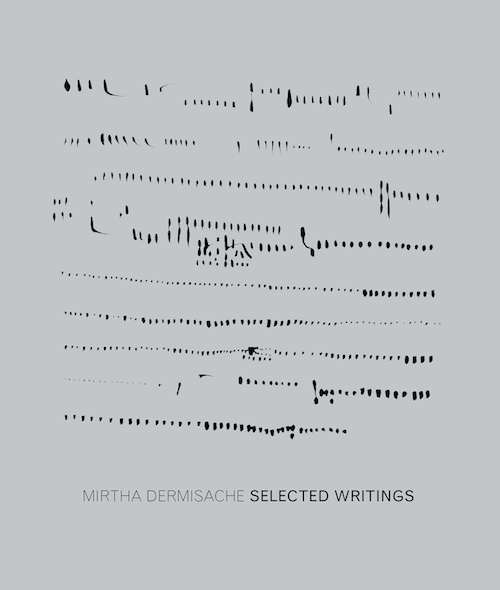

A week before I boarded the airplane, a sleek gray book arrived on my doorstep: Mirtha Dermisache’s Selected Writings. I opened the book—white background with blue, hieroglyphic-like texts—and didn’t put it down until I’d examined every page.

‘Mirtha Dermisache: Selected Writings’, published by Siglio and Ugly Duckling Presse, 2018.

‘Mirtha Dermisache: Selected Writings’, published by Siglio and Ugly Duckling Presse, 2018.

*

“I started writing and the result was something unreadable.” Dermisache said. Born in Buenos Aires in 1940, Dermisache started publishing her texts the year she turned 27; her first book was filled with what looked like illegible writing, scribbles and strokes that resembled wave graphs or clusters of yarn.

“I was always a little hermit,” she said in an interview for Pabellon de las Bellas Artes. “I worked alone and did not belong to any group… but thanks to an acquaintance, I got a printing press that bound my 500-page book! It was the only book I had. The paper was common, it was not a special paper. But anyway, it had 500 pages.”

“Nobody will understand what you are doing,” said filmmaker Hugo Santiago when Dermisache showed him her work. “The only one who can understand is Jorge Luis Borges, but Borges is blind, so you have no chance.”

Was writing considered writing if there were no identifiable words? Dermisache’s writings curve and swivel across the page; the shapes contort into a mesmerizing mesh, at times they resemble a skein of wool or a complex mathematical equation. Looking at it was like viewing a complex future language that rejected both syntax and form, or a child’s first unsullied experiments with handwriting. Either way, I felt lost in its beautiful intricacies, the proximities of language just out of reach.

*

Berlin is a vast city, unwalkable; barren in mid-winter. I was surprised that whenever I strolled through my Neukölln neighborhood, the streets were almost completely empty. Eerily quiet sidewalks, walls strewn with graffiti. Everything was gray. The river, the buildings, the horizon with its theatre of low clouds. My first morning I woke up in an ocean of cold bed sheets. I got up and opened the french doors leading from my bed to the terrace. Everything in the unfurnished room bathed in a gray, effervescent light.

Photo by J. Mae Barizo.

Photo by J. Mae Barizo.

There is a German word, unheimlich, that translates in English to “uncanny, weird.” But the core of the German word is Das Heim: the home. Freud used the term to denote an emotion that was strangely familiar that resulted from the repetition of the same thing, like becoming lost and accidentally retracing your own steps.

That was also how it felt, opening up Dermisache’s gray book—unheimlich; the gestures were familiar but the meaning was ungraspable. One could describe the thickness of the strokes and the position of the text on the page, but the shapes themselves had no hierarchical order, a turbulent river of text running across a page.

The drawings are endowed with a sense of otherness, a kind of detachment from certainties. The work exists at the intersection of the graphic, the linguistic, the literary. The white area surrounding the illegible text struck me as poetic; was Dermisache a poet? I wondered. Poets understand that blank space is as important as the spaces where writing appears. Margins act as unadulterated space where thoughts can cluster, ideas can materialize.

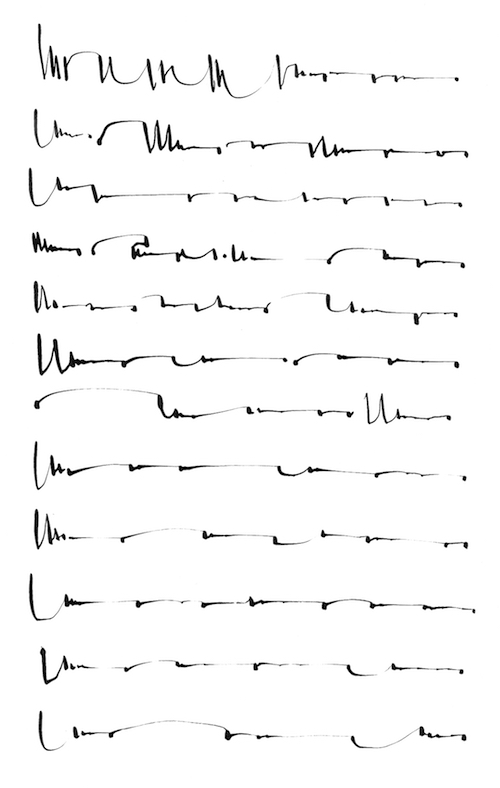

‘Diez y Ocho Textos’ (Texto 9), 1978, ink on paper.

‘Diez y Ocho Textos’ (Texto 9), 1978, ink on paper.

*

Hugo Santiago took one of Dermisache’s books and gave it to Roland Barthes. A year later, Barthes wrote her:

Paris, March 28, 1971

Dear Miss,

Mr. Hugo Santiago was kind enough to show me your graphics notebook. Let me just tell you how impressed I am, not only for the highly artistic quality of your strokes (which is not irrelevant) but also, and especially, for the extreme intelligence of the theoretical problems related to writing that your work entails. You have managed to produce a certain number of shapes, neither figurative nor abstract, that could defined as illegible writing—leading to suggest its readers, nor exactly messages nor the contingent forms of expression, but the idea, the essence of writing.

Dermisache stated that the letter from Barthes was the first time anyone had labeled her work “writing.” It was the confirmation she needed, a kind of permission to continue with her creative undertaking. Barthes’s phrase, “the essence of writing” is accurate; “Nothing is more difficult to produce than an essence… Haven’t the Japanese artists devoted a lifetime to learn how to draw a circle that does not refer but to the idea of the circle itself?” he wrote.

In Dermisache’s work, which resists conventional interpretation, she dispenses with the semantic meaning attached to words altogether; writing that does not refer to language but rather the idea of language itself. Essence, in fragrance, referring to the primary element, or distillate. Language boiled down to its concentrate.

*

High on a manmade hill in West Berlin is an abandoned spy station built on thousands of tons of post-WWII rubble and debris, believed to be created from the remains of 400,000 buildings. Buried deep in Teufelsberg (translated as Devil’s Mountain) a building still remains, once a Nazi military-technical school; the Allies found it easier to bury the behemoth than to blow it up. The listening or intelligence gathering station was run by the American NSA and the British to eavesdrop on the Soviet armed forces, Stasi and communist East Berlin.

Teufelsberg isn’t a subtle sight: three enormous globes, the highest looking like a giant condom, tower over the Grunewald district. Teufelsberg’s function was to listen: each radome globe contained satellite antennas and some of the most sophisticated spying equipment made, which intercepted Morse code signals, radio waves and other illegible transmissions, which were then interpreted and analyzed.

What was there to find with such intense spying? It made me think of Dermisache’s drawings, which conjure up redacted CIA reports, bullet-marked walls in war zones, tallies of days remaining in jail, EKG charts, squiggles of sperm, so many other things.

The drawings at first glance look deceptively simple, strips of indecipherable writing rendered in black or blue. For me, it was the proximity to language and even music, that was intriguing. Some writings seemed like an elaborate code, secret communication from an unknown land; others were like knots or seismic waves; my favorites were the ones that looked like an inked spider had traveled precariously along a white page.

‘Sin título’ (Texto), no date, c. 1970s, ink on paper.

‘Sin título’ (Texto), no date, c. 1970s, ink on paper.

*

It was that journey—from disorientation to the familiar—that I was after, a realization I had after getting hopelessly lost and then a little less lost, wandering the dark alleys of Neukölln. The street names were difficult, pronouncing them felt like chewing a handful of nails. But I was happy; I was far from the numbered streets and grid structure of Manhattan and I reveled in it. Memorizing the avenues of my new neighborhood—Karl Marx Strasse, Sonnenallee, Weserstrasse—felt like understanding a small piece of the world while still feeling as lost as before. I understood that I had to pass those streets before reaching the river that marked the end of my Kiez and the start of another one. “After the river you’ll pass Kotbusser Tor, or Koti, as the Berliners say. The drug dealers hang out at Koti, but don’t pay them any attention at all,” my friend said after she told me how to walk to Kreuzberg, which used to be the Turkish heart of the city and now is a gentrified area full of high-end design shops and galleries, filled with young people lounging lazily in hip bars and coffee shops, looking impossibly cool.

*

In one of those fashionable cafés, one that looked like it had been bombed in the war and remained untouched in its ruinous grandeur, I opened the book again. The Dermisache works I liked best looked to be done with a simple ballpoint or perhaps a calligraphy pen. On the page they looked readable, touchable. The lines were full but the margins were clearly delineated; wave-like oscillations spanned the page, alive with meaning. Each line was slightly different than the next, every image had a unique lexical structure; the work suggested narrative, but resisted interpretation. Dermisache’s texts worked in the way good poetry operates, welcoming the reader, while not letting them completely in. It captured the longing I felt when traveling to foreign places, but also the familiarity of my childhood, deciphering a stranger’s handwriting on a page. Is it true that we are drawn to the image of an artist, or a writer, because we imagine that in their moment of creation they are a closed circle? What moves me is this distance between knowing and unknowing.

*

Something about Berlin’s fractured landscape, my fixation with geography and memory, made it the ideal place for me to write. The Berlin Wall, the spy stations, the post-apocalyptic aura of the place, accented negative space like a square of Dermisache’s text on a blank, unadulterated page. I was trying to span the gap between the seen and unseen, the documented and undocumented, between we and them. I lay in the gray bed and thought about the distance between things—the miles I’d put between me and my family, the space between the country my parents left behind and the place where I now was.

Argentine writer Julio Cortázar wrote that, “Writing is rarely the pursuit of answers, but is rather about investigation, of the self, of one’s work and the world at large.” More honest to the process of writing, Cortázar suggested, was the process that embraced not knowing. I compared it to the babbling of an infant, which seemed to have no meaning except to expose a desire for speech. Or Dermisache’s drawings, its frequent code-switching of shapes displaying a longing for language without the semantics of conversation or words. The sense of estrangement, the desire for connection, existing at the level of pen on the page. Her drawings worked as a kind of bridge, a polyphonic crossing of cultures and codes, a form of resistance against the officialness of language.

I wandered the city, trying to walk off my anxiety. Erin Mouré wrote: “Poetry is the limit case of language. It is language brought to its limits and where its relationship with bodies and time and space can crack open.” It is these limits my father spoke of, coming to a new country, reading between the lines. It is the unbridged fractures of Dermisache’s drawings that felt most faithful to the physical displacement of being a stranger in a bleak, beautiful city. Art as an ongoing translation between here and there, east and west, knowing and unknowing.

__________________________________

Unless noted, all images from Mirtha Dermisache: Selected Writings, published by Siglio and Ugly Duckling Presse, 2018. Courtesy of the Mirtha Dermisache Archive.