Lost and Found: KB Brookins on Masculinity, Gender and Trauma

"I was a girl in the imagination of others and nowhere else."

Contending with My Want (To Be Normal)

In all my childhood dreams, I was a boy.

Meaning in all my dreams I had 3C hair,

yellow skin, phenotypically Black features

like full lips and a crisp hairline only a Black barber

can bless you with. I was a cis boy.

In this version, the most the desirable by those I wanted

to desire me—Black girls of any shade and body type,

Black boys with long torsos and too much shame

to waste on footballs and bad dreams. I had clothes.

Mannerisms and idioms like damn, girl and my dude

and a face that is wanted and easy. A non-twisted walk.

Teeth straight as my deepest desires

(to be wild enough in my want), straight like

lines where the razor hits my forehead and sideburns.

I had a beard and a girlfriend or two. Everything

a beloved human in Black heaven, which is desire,

could want. I had a working definition of family.

He had a family that wanted him home.

*

Lost

This day in church, I stood next to Mama. I was a praise dancer, prancing into small church aisles singing “Silver & Gold” by Kirk Franklin. We all wore stockings and headbands; I wore multicolored barrettes and a cotton white shirt with a collar. My shirt was tucked into a dress, plaid-patterned and bigly loved amongst the usher women at church. I was the smallest boy praise dancer in church, and everyone loved me so much that I always inherited aunties and cousins. There are many pictures of me in that church smiling, crawling, always being the center of someone’s attention. My clothes, and church activities, and life, came from choices made by somebody else. But I was five, heavenly innocent in the year 2000, unassuming and in adoration of a new, indubious world.

I remember being a woman before I could ever be a girl.

While Mama talked with adults after service, I played tag with the other church kids. I said “You’re it!” when inevitably picked as the runner and tagging someone else. I was told by kids and adults alike to “slow down” and “play softer,” often. This day, out of the many Sundays we spent in this big, redbrick church, Mama called me over to her and my aunt Fey (aka Mama’s friend from church). They were joined by a boy whose dick was in my mouth earlier that week who looked angry about something. He looked something like a pit bull who knows they peed in a corner inside.

“You know when you did that thing for me earlier this week? That wasn’t supposed to happen,” he said, weighed down by his got-caught guilt. Two adults decided that now, in the middle of a game of tag, outside of a church building after we heard the preacher preach about submitting ourselves to Christ (whatever that means), was the time to address the sexual violence that was happening under everyone’s noses. What am I supposed to say, I thought to myself. For months, three boys violated me unchecked; this happened every time my aunt Fey was supposed to babysit me, and instead left me alone with her three boys and daughter, which was often.

“I’ll throw you in the air and make you laugh all day long; just do this for us,” the teenage assaulters said on nights I stayed with them. I don’t remember much of this time in my life, but I do remember that the boy at the church that day was the only one that got caught. I do remember their beards, how age sat differently on them than me, their insistence that doing this, putting their genitals in my mouth, would be fun, that they would throw me in the air like the little girl I was after I did a teenage task for them. I remember every Sunday, me in stockings and them in tall tees, my body unscathed, their clothes laced with weed that darkened their lips, the dark house made even darker with secrets and nobody around to raise these brothers, my questions, my body, my reluctant yes. I remember my lack of thinness from birth, comments about my weight from these teenage boys within minutes of meeting them. I remember being a woman before I could ever be a girl. I was a girl in the imagination of others and nowhere else.

Of course, there were families in the church that knew about them. The delinquent teenage boys that my aunt Fey raised, the boys with thirty-two teeth and insatiable hunger for animals girls in lower food chains with shorter legs to run. I listened to the gossiping about them.

“They need to get baptized,” another aunt said.

“They are just being boys,” her husband, a grown man who excused their violence, countered.

The only language I had for responding to betrayal, violence, and insincere apologies at five years young was “okay.” I whispered this, unable to make eye contact with a boy who willfully manipulated me, and he nodded his head in silence. I knew something about what they made me do was wrong; anything that you won’t do when your mama’s home is wrong, usually. I kept playing until we went home. We switched churches and never talked about this incident again.

There is no accountability to bestow on ideas, just stories.

At the age of five I started to go missing. I was the lovable girl caricature of a human my parents wished and wished for. Surprisingly, I’ve grown to not blame my aunt. How could she have known that her sons would do such a thing to another child? How could she have known that a boy, even when you are a single mother, even when there is no man around to taint the ways they think about women, even when you drag them to church every Sunday, will learn what it means to be a man through the exploitation of women and girls? It would be too simple to hold contempt for a woman who, like all women I grew up around, was trying to survive. To this day, I’m not sure I’m even mad at the boys. The adults that let them terrorize girls unchecked, and the systems that reward patriarchal violence, and the mentalities that let church grounds continuously be the grounds where sexual assault blooms, and the silence, the loud, terrorizing silence that left me with questions for decades, are the real culprits. But there is no accountability to bestow on ideas, just stories. So I’m telling this to you for the girl I was, and the girls that unfortunately feel me, too.

*

Every day I wake up and a Black boy girl goner has gone missing or uncared for. Or erased by communities meant to protect them. Every day I wake up and even more people like me, little boy girl miracles, are uncounted to begin with. I create the other side inside of me with every injection I fill with a syringe and shoot into a muscle.

You see that light flickering in the distance? You see men, repenting and skipping out on their well-known sins? You see the thinness of that woman’s grief ? You see the love nested in that man’s person’s beard? You see gender, spinning and fusing into something freer? You see the tree, connecting roots underground with their siblings in the middle of a storm? You see that present left outside a dark room?

I am no longer lost. Can you find me here?

__________________________________

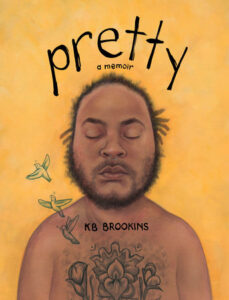

From Pretty: A Memoir by KB Brookins. Copyright © 2024 by KB Brookins. Published by arrangement with Alfred A Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

KB Brookins

KB Brookins is a Black, queer, and trans writer and cultural worker from Texas. They are the author of Freedom House and How to Identify Yourself with a Wound. Brookins has poems, essays, and installation art published in Academy of American Poets, Teen Vogue, Poetry Magazine, Prizer Arts & Letters, Okayplayer, Poetry Society of America, Autostraddle, and other venues. They have earned fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, PEN America, Equality Texas, and others.