We must be prepared for things turning out differently than we expect.

In the plane to New York, she had a plump, permanent-waved, chatty seatmate who pried things out of her, for instance that she had grandchildren. Lorna loved her grandchildren but didn’t think of herself as a “granny,” which was how the woman next to her put it. “I’m a granny,” she said. “How about you? How old are yours?” Lorna had to think: it changed all the time. Julie must be about twenty, twentyone, and Curt’s twins, what, four? She didn’t inquire about the ages of this other woman’s grandchildren and, though she wasn’t in denial, did wonder if her own age and grandmotherhood would detract or add to her authority as an art critic. For a man, it would add, or be irrelevant; for a woman, she didn’t know.

“Where are you from?” persisted the irritating seatmate. “Were you on vacation?”

“Originally San Francisco,” Lorna said, “but I’ve been living overseas.” She had learned over the years to say “overseas,” like a military wife, instead of “I live abroad” or “I live in Europe,” which could seem elitist or excite the suspicion you were CIA.

“Are you happy there?”

Lorna thought it an odd, unanswerable question, and rather nosy, too. What would most people say? Yes, when they really weren’t, or no, though they were? Did people even know? Happiness was like one of those floaters in your eye that you can never focus on, intangible and fleeting. But she knew she was happy at the idea of wonderful America, its big mountains and expansive generosity—happy to be going there, to be home again permanently after all these years away.

*

In the twenty years she’d lived in France, Lorna had often come back to America, to San Francisco to visit her children or, in the first years, to New York or Massachusetts or even South Dakota to give lectures, keeping her professional life going. Then her lecture engagements had begun to taper off, almost without her noticing. So, today, it wasn’t exactly culture shock, arriving in New York, it was the new finality of her plan to stay that made her appreciate pleasant American things— the cheery man in customs who said “Welcome home” to people in the U.S.-citizen passport line; drinking fountains; the smiling face of the handsome new president, Obama, on posters in the reception hall.

She felt a surge of sentimental patriotism, of oneness with her native land. America was more suited to her temperament than the exigent rectitude of formal, starchy France. She was home; maybe she’d been homesick these twenty years. Missing the open faces, enchiladas, Japanese cars.

She would postpone the unwelcome task of giving the news of her whereabouts to the children and facing their questions. But she did call Margaret, Peggy, her oldest child, who lived in Ukiah, California, and was recently divorced from her husband, Dick Willover, a man whom both Lorna and Ran (Randall Mott, Peggy’s father) had been crazy about at first. Tant pis. Lorna predicted Peggy would be the most understanding. She telephoned her from the hotel.

“Peg, it’s Mother. Are you there?” “Mom! Where are you?”

“I’m in New York, honey.” How to explain? “I’m on my way to San Francisco, then Bakersfield, where I give a lecture. I should be there by Wednesday. I’ll explain it all in the fullness of time.”

“Are you coming here? Is Armand-Loup with you?”

“No. Peg—I’ll be staying in San Francisco awhile. Armand and I are taking some time off. Don’t mention it to Hams or . . .”

Predictably, Peggy remonstrated. “Time off? Are you leaving him? That’s terrible, Mother. Are you sure? Have you seen a counselor? What’s the matter?”

“Please, Peg. I’ve analyzed my situation. With all its dismaying ramifications . . .” She spoke in a light tone. She herself would have to understand better before she could explain.

“I suppose you have,” Peggy conceded. There were a number of negative ramifications Lorna was only now seeing. For instance, how much detail about all this was she really going to go into with the children? She had not been feeling that she needed to explain to them about her return, but now she was obliged to recognize that she was uncomfortable telling them her main reason for leaving Armand-Loup. It was his wild infidelity. Infidelity at their age was embarrassing, maybe even comic, because at their age—the children probably thought—you were supposed to be not only beyond caring but beyond doing anything much, and way beyond enduring the rituals and incurring the expense of illicit sexual capers, in Armand-Loup’s case the escalating expense of wooing demanding, ever-younger young women.

She had been surprised by his infidelity. She knew the reputation of French husbands, but she had believed it was overstated, Frenchmen being more or less like other men, with normal physical capacities and the normal wish to avoid trouble. Besides, she had thought that she and Armand-Loup got along very well in that department of life. She also knew that French wives would, or would have in the past, turned a blind eye, or exacted some domestic price in private, to compensate for the dinners, the flowers, the concerts, and weekends spent with poules de luxe. Lorna begrudged both the time and the expense of Armand-Loup’s adventures. And in his case, the costs had risen with his weight, and he was now rather plump—he who had been such a beauty, and a fantastic skier. Now the girlfriends were younger, plainer, and more expensive, especially a couple of expensive medical events involving these young women. With their cost, eventually, had come the need to sell the house, though this exigency was disguised even in their private conversations as sensible downsizing.

And though she understood that he was trying to fend off age, bon, as a result of his betrayals she had become less and less motivated to throw herself into her assigned duties as helpmeet—why would you want to slave for a man who was weekending with some chick in Bordeaux? And there were larger cultural issues: whatever she did, in their village, she’d always be the awkward American woman, never quite right, said to once have had some career in America, but never, ever getting the cheeses straight. All was failure.

And yet—and yet wasn’t there more to it? A more positive force had also prompted her to leave. Her own sense of adventure? Of not wanting to feel that life was just reaction to fate, or to the infidelity of someone else? Was it wanting to have a new life while there was still time? Was she having a midlife crisis in an interesting way? Okay, too late to become an opera singer or a congresswoman, she still looked forward to the new chapter.

Twenty years ago she had gone off with such glee with her hot French husband, leaving the children to their adult lives: the newly married Peggy with her baby, Curt and Hams in college. Over the twenty years, all of her kids—Peggy, Curt, Hammond—and in time their spouses and kids had loved their holidays and summers in France, in her postcard-perfect stone farmhouse, mas, in Pont-les-Puits. They loved to loll in the sun of its courtyard, hike the pretty mountain paths, and feast on the special foie gras and fragrant chèvres of the region. She had had little reason ever to come back to America.

How much did a grown-up like herself need to reveal to her adult children anyhow? Did she owe them explanations? Had the balance already tipped on the dependence scale toward her being more dependent on them than they on her? She didn’t think so, but maybe they thought so.

She was unwilling to struggle with the matter of her official story for too long and thrust it from her mind, giving Peggy the cheerful version: grown apart, missing America, never really at home in France, lonesome for you children, also the grandchildren, wanting back into her intellectual life while she still had her wits about her . . . ArmandLoup, she explained, was selling the charming village house. There had been no question of her staying in the house at the time of the separation discussions, as it had been his to begin with, and his to sell, as he was now trying to do, very reluctantly.

At moments when her positive spin collapsed, she knew that coming back to the U.S. was a question of supporting herself, and she painfully foresaw that her career, however well she could manage to reestablish it, would with age inevitably wind down, along with the enthusiasm she felt now for writing new material, doing research, and keeping up with art historiography.

Now, sitting in a hotel in New York City, she was overtaken again by other negatives of what she was facing—the hurly-burly of the lecture tour, of mediocre library venues in Bakersfield or Fresno, even fears about her physical stamina; she’d been so tired last night, and she wasn’t a tired person. What if she was coming down with something, the onset of some condition appropriate to her age that she would henceforth have to think about? People her age got diabetes, they got arthritis; they had to allow for their health, had to carry an embarrassing doughnut cushion with them, or an oxygen bottle, or excuse themselves to take medicine, or sneak pills into their mouths at table with that furtive sidelong look.

And yet, wasn’t America the better place, where opportunity beckoned at any age, and people were not so conscious as the French of what other people thought? Ça ne se fait pas, said the French. That isn’t done. In America, you could do it.

__________________________________

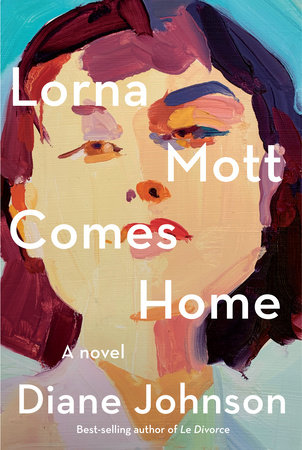

Excerpted from Lorna Mott Comes Home by Diane Johnson. Copyright © 2021 by Diane Johnson. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.