Looking for Middle-Earth? Go to the Middle of England

John Garth on the Landscapes That Influenced J.R.R. Tolkien

For Tolkien, England was a land of revelation. Though he had English parents, he was actually born in the African veldt, in January 1892, and so it was as a newcomer that he arrived in what became his homeland. In April 1895 he was brought to stay with relatives as a long break from torrid Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State, now part of South Africa. He never saw his father again.

Arthur Tolkien died from rheumatic fever a year later, alone in Bloemfontein. The sharp lesson that nothing is permanent was to be repeated by later moves and bereavements, and by much bigger changes.

Meanwhile, the change of scene was profound. Young Ronald Tolkien had left a land where the summer sun had been so intense that the curtains remained drawn at Christmas. Now he fell in love with the West Midlands landscape of elms and small rivers, and with the air of the country folk.

But he would later reflect that the experience went both deeper and wider. It left him permanently with “a very vivid child’s view.” In a sense, all his fictional landscapes stem from this experience. “The English countryside,” he said, “seemed to me wonderful. If you really want to know what Middle-earth is based on, it’s my wonder and delight in the earth as it is, particularly the natural earth.”

Reaching far beyond England, it meant the “North-Western air” of Europe as a whole struck him “both as ‘home’ and ‘something discovered.'”

In his own stories, it is remarkable how often the adventurers arrive unexpectedly in havens of rest that are at once both strange and welcoming—Beorn’s hall, Lothlórien, Gondolin, Rivendell, the house of Tom Bombadil. Some of his travelers cross the sea and reach a “far green country” that is founded upon Tolkien’s first encounter with England.

Here, it would seem, is the source of that acute taste for the sudden, unexpected uplift he found in fairy-stories, a glimpse of “Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.”

Lee Webb Nature Photography / Alamy Stock Photo

Lee Webb Nature Photography / Alamy Stock Photo

The sudden dislocation between old and new worlds also gave Tolkien a kind of visionary superpower. He would always retain a vivid mental picture of a house that never actually existed—an elaborate fusion of his old Bloemfontein home and his grandparents’ Worcestershire house in Ashfield Road, Kings Heath. He compared the image to a photographic double exposure. Another process of his imaginative life was forming: the ability to visualize unreal places perfectly, and the tendency to project the world he inhabited onto one he only imagined.

*

The Shire is a reflection of Sarehole, a hamlet that lay about a mile and a half eastward from Kings Heath. It “was inspired by a few cherished square miles of actual countryside at Sarehole,” he told a newspaper. To his publisher, he said it was “more or less a Warwickshire village of about the period of the Diamond Jubilee”—Queen Victoria’s sixtieth year on the throne, 1897.

From the summer of 1896, Mabel Tolkien rented 5 Gracewell Road, a new semi-detached cottage that looked downhill to the little River Cole and a mill with a tall chimney and churning waterwheel. Though only five miles from the center of booming industrial Birmingham, Sarehole itself stood in a country that was still little altered by the modern age.

The horse ruled the roads. On a clear night, the stars ruled the sky. It was a world that had more in common with “the lands and hills of the most primitive and wildest stories,” Tolkien recalled. “I loved it with an intensity of love that was a kind of nostalgia reversed”—an aching love for a new-found home.

For Bilbo, seeing Hobbiton again after his great adventure, “the shapes of the land and of the trees were as well known to him as his hands and toes.” Though Tolkien could never return to the Sarehole of his youth, he declared more than 60 years later, “I could draw you a map of every inch of it.”

No adult gets to know a small area like a child—or indeed like a hobbit, close to the ground and sharply attuned to nature. Ronald and his brother Hilary, two years his junior, would hang around the watermill, where swans glided in the willow-encircled pool. They would play in the mill meadow with its huge sentinel oaks, explore the big sandpit just up the road or disappear into a “wonderful dell” with flowers and blackberries. They called it Bumble Dell, from the local word for blackberry. It has been identified as Moseley Bog.

Tolkien once said he “took the idea of the hobbits from the village people and children.” He mixed with the local boys, “fascinated by their dialect and by their pawky ways.” Among other things, the dialect word pawky means impudently inquisitive. It is the kind of attitude he would attract effortlessly, with his long hair, his “Little Lord Fauntleroy costume” and his educated air. He was a Baggins among Gamgees.

There would also be visits to an uncle two miles away in Acocks Green, and walks further afield. “Children walked long distances in those days,” said Tolkien. They also told tall tales. No doubt it was Ronald who convinced Hilary that a black witch lived in the nearby windmill and a white witch in the cottage sweet shop. He was already getting into his stride, making the familiar landscape into a perilous realm.

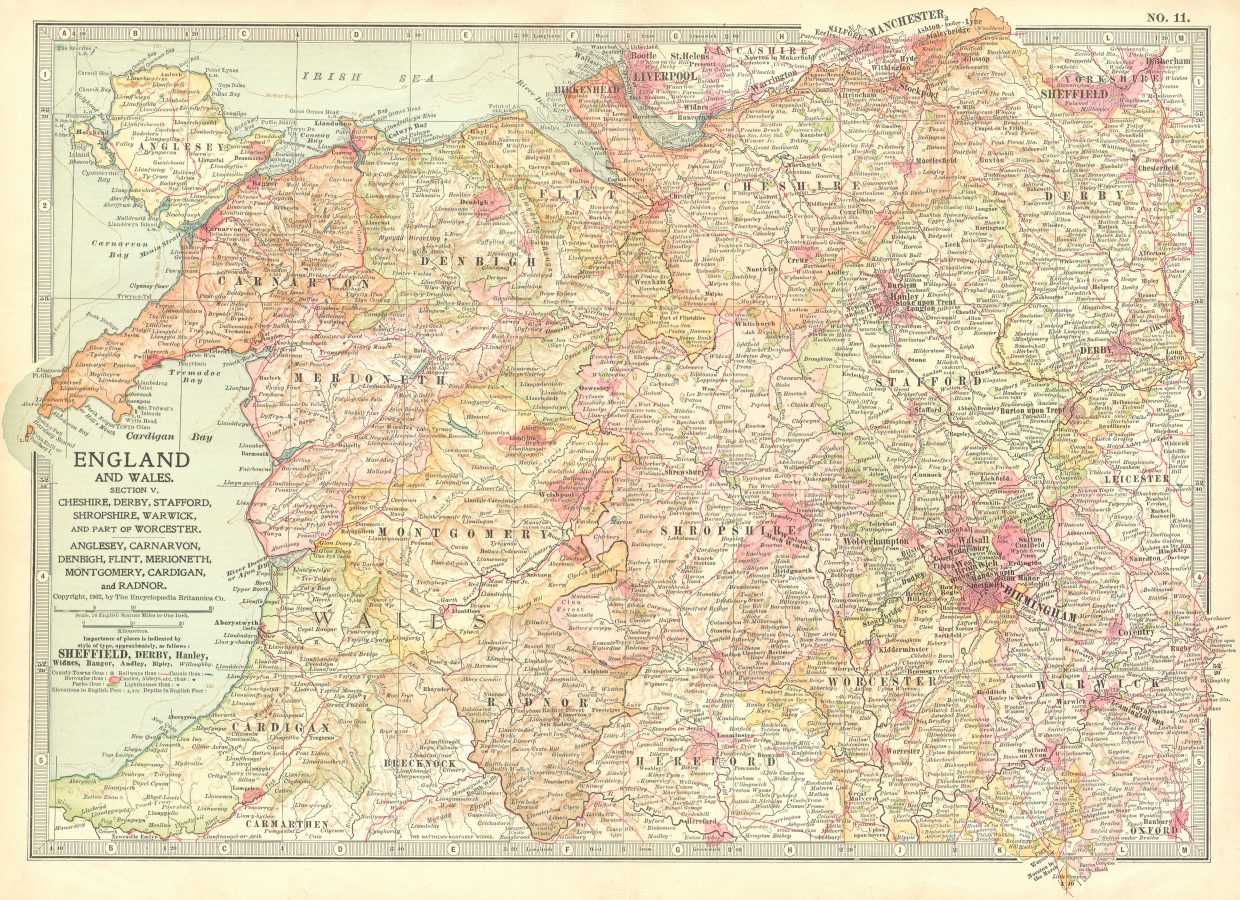

Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock Photo

Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock Photo

What Sarehole did for his books was the exact opposite. Within the vast and ancient world of dangers and enchantments, it conjured a place where you could have tea, check the clock on the mantelpiece and stroll to the post office or play on the green.

The Hobbit was begun in 1928 or more likely 1929, when Tolkien’s sons turned twelve, nine and five—his own age at Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. He was inviting them to join him in his own childhood world, not too distant from theirs, to set them on the road to distant lands of adventure.

*

The Sarehole idyll ended quickly. At eight, Ronald won a place at King Edward’s School in Birmingham. It was an eight-mile round trip from the village, half of it on foot. Nor was it much easier getting to the city-center church that they now attended since Mabel had embraced Catholicism. So from 1900 they moved into a succession of houses closer to the city with its crowds, noise and smoke.

A brief return to the countryside came four years later after Mabel fell seriously ill with diabetes. A Catholic priest friend from the Birmingham Oratory arranged for her to convalesce with the village postman and his wife at Woodside Cottage, Rednal, near the Oratory retreat south of Birmingham. Ronald and Hilary, sent elsewhere while their mother was in hospital, now rejoined her.

In glorious weather, they had the best holiday of their lives, flying kites with Father Francis Morgan, picking bilberries, sketching and climbing trees. The Oratory property backed onto the wooded Lickey Hills, where the boys could roam freely. They looked “ridiculously well compared to the weak white ghosts that met me on the train 4 weeks ago,” wrote their mother.

In November 1904, Mabel Tolkien died. Tolkien once said that his writing about hobbits “began partly as a Sehnsucht”—a wistful yearning—”for that happy childhood which ended when I was orphaned.”

Sarehole itself would not last for long. Absorbed into busy suburban Hall Green, it has lost even its name. Moseley Bog is now on a “Tolkien trail” running through what has been renamed the Shire Country Park—a thin ribbon of green along the Cole. A Middle-earth Weekend takes place annually, centred on Sarehole Mill—a gentle tribute to Tolkien’s “lost paradise” of all-year-round green horizons.

*

Tolkien did not copy Sarehole as Hobbiton. Hobbiton has no wildwood. Sarehole has no high hill. His instinct was to dip, mix and layer, drawing from personal experience, reading and imagination—a touch from here, a hint from there, a flourish out of nowhere. He also said the Shire was based on his memories of visiting the Worcestershire smallholding that Hilary bought after the First World War, or the Great War as their generation knew it.

Tolkien felt an umbilical connection with the Vale of Evesham, ancestral home of their mother’s family, the Suffields. As he grew up, and during his undergraduate years at Oxford (1911–15), he delighted in train journeys here. Later he would take his children to see their uncle and cousins at the farm, at Blackminster near Evesham, where they would fly kites or help to pick plums. The River Avon winds lazily through heavy soil ideal for fruit, so the whole vale thronged with market gardens and orchards like Hilary’s.

During a summer visit in 1923, Tolkien convalesced from severe pneumonia and turned again to the mythology he had begun to create during the war. In the following years he would also begin to write for his children, weaving familiar landmarks and place-names into the stories. In one, Roverandom, a wizard asking for directions home to Persia is misdirected to Pershore, near Evesham, and becomes a fruit-picker.

Another tale, Mr. Bliss, features a hair-raising motor tour among fields and hills, country inns, church spires, walled kitchen gardens and a picturesque village. Tolkien’s delightful illustrations make it all look much like the Cotswold Hills, between Oxfordshire and the Vale of Evesham. A hilltop panorama looks past a nestling village and across a broad valley to distant hills. Such views can be had from the western edge of the Cotswolds around Broadway Tower, looking across Hilary country towards Bredon Hill and the heights of the Malverns and Wales.

Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull suggest Mr. Bliss may have been created during a visit to Hilary’s. (By one account, it was inspired by a 1932 trip there, when Tolkien managed to damage a dry-stone wall with his new Morris Cowley. Another account puts it four years before they bought the car, which would make Mr Bliss’s driving rather prophetic.)

Oxford had already made its mark on Tolkien’s writing while he was an undergraduate and in the first of his mythological Lost Tales. After he returned from Leeds to Oxford in 1925, family walks or drives were fuel for his imagination. So Tom Bombadil sprang into being. The name first belonged to a jointed wooden doll, one of the Tolkien children’s toys, but escaped into much larger life. The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, a poem of 1931 or earlier, has him gallumphing from hill to dale to water meadow, among water-rats and bumblebees, laughing in sun and rain alike.

Bombadil was not yet part of Middle-earth. In 1937, desperate for something to follow up The Hobbit, Tolkien offered him to his publisher as a standalone figure embodying “the spirit of the (vanishing) Oxford and Berkshire countryside.” But if Bombadil is a genius loci or guardian spirit of place, as Tom Shippey says, then he is also merrily at odds with his neighbors. He masters them all—badgers, barrow-wights, Willow-man, and River-woman’s daughter.

He delights in nature like a child immune to its dangers, or like a Thames Valley Adam. When Tolkien absorbed him into The Lord of the Rings, he tied Bombadil’s power to song and made him “Eldest”—like the primal Finnish hero Väinämöinen, I suggest, “but perhaps with a bit of Oxfordshire ploughman thrown in,” adds Oxford medievalist Maria Artamonova.

Murmuration of starlings, Otmoor.

Murmuration of starlings, Otmoor.

And though his countryside might be vanishing, Bombadil carries no trace of the kind of melancholy or portentousness that Tolkien expressed elsewhere, such as Lothlórien.

Tom had first appeared in a rowing song with real and concocted English place-names, and in a story fragment set in Britain under a pseudo-historical King Bonhedig. It sets the tone for another tale inspired by the counties around Oxford, Farmer Giles of Ham. Here, the country around Oxford belongs to a “Little Kingdom,” in what Tolkien called “a no-time in which blunderbusses or anything might occur,” though it is between the Romans and King Arthur.

The tale refers to real places—Thame, Oakley, Otmoor, the standing stones of Rollright. Yet the fictional topography is as pick-and-mix as the era, so that even though the named locations still exist, “there is little point in visiting them looking for Gilesian landmarks,” as Brin Dunsire says.2

Farmer Giles of Ham is really about place-names rather than places—a frolic through the mistaken folk etymologies that frequently attach to obscure names. Tolkien said it came out of a “local family game played in the country just around us.” The whole story is an elaborate false explanation for the name of the Buckinghamshire village of Worminghall, a few miles from Oxford.

Tolkien makes it the hall of the Wormings, descendants of a farmer who tamed a dragon or worm. This is entertaining nonsense (it originally meant the field belonging to someone called Wyrma). A much later story, Smith of Wootton Major, features unexplained, but equally convincing, place-names.

England has an embarrassment of Woottons, with three in Oxfordshire alone. This 1960s story surely refers to none of them. Wootton, simply meaning “settlement in a wood,” marks the fictional village as utterly ordinary—though it is a hidden gateway to the forest of Faërie. When Smith’s fame spreads from Far Easton to the Westwood, Tolkien is punning on eastern and westward.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien: The Places That Inspired Middle-earth by John Garth. Copyright © 2020 by Quarto Publishing plc. Text copyright © 2020 John Garth. Published by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.