Looking at Willa Cather’s Lesbian Partnership and Domestic World

The Lesser-Told Story of Cather and Edith Lewis

In 1930, the novelist Willa Cather and her partner, advertising copywriter Edith Lewis, spent six months in Europe. In the hot month of August, they stayed at an old hotel in the spa town Aix-les-Bains, France, where Cather had stayed before. The two of them “so often admired” an “old French lady” they saw in the hotel lounge.

One night, this woman offered Cather a cigarette, and they struck up a conversation. After several more conversations, Cather still had no idea what her name was. After she and Lewis returned from a trip up into the nearby mountains to escape the heat, the old French lady greeted Cather “very cordially” and suggested they meet in the salon after dinner, where Lewis joined them.

As the three conversed, the “old lady made some comment on the Soviet experiment in in Russia,” and Lewis remarked in response “that it was fortunate for the great group of Russian writers” (Leo Tolstoy, Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Turgenev) “that none of them had lived to see the Revolution.” In response the old lady astonished them by saying that she had known Turgenev “well at one time.” Lewis’s offhand comment about 19th-century Russian authors led the old woman to disclose that she was Caroline Grout, niece of Gustave Flaubert, one of the great novelists of 19th-century France.

Cather described these events in a 1933 essay she titled “A Chance Meeting.” Mme. Grout’s identity and its revelation are the subject of Cather’s essay, but in it, Edith Lewis is identified only as “the friend with whom I was traveling.” I spent eighteen years researching and writing my book about Cather and Lewis’s relationship, The Only Wonderful Things: The Creative Partnership of Willa Cather and Edith Lewis (2021). It was my own chance meeting in 2018, late in my research, that led me to discover one of the great secrets of Cather’s late life and death.

I was invited to present on my research at a conference in honor of Caroline Schimmel, a book collector who had given a substantial portion of her collection on the theme of “women and wilderness” to the library of the University of Pennsylvania. I had long known that Lewis had called a physician to the Park Avenue apartment she and Cather shared less than an hour before Cather’s death. This physician, referred to only as Dr. White in a letter from one of Lewis’s sisters to their brother reporting Cather’s death, had arrived just in time to pronounce Cather dead.

I despaired of ever identifying a doctor with such a common surname, but when Caroline Schimmel saw my name tag, she said, “You are the person presenting on Cather. My grandfather was her doctor late in her life.” “Dr. White?” I responded with excitement. “Yes,” Caroline continued. “Dr. William Crawford White, and he was a specialist in breast surgery, so she must have had breast cancer.”

I was skeptical. Because of my research for the book and because of my work as an editor of the Complete Letters of Willa Cather, I knew a lot about Cather’s medical troubles: her problems with an injured tendon in her right thumb, her severe anemia, her surgery to remove her gall bladder and her appendix, even her difficult menstrual periods and her struggles through menopause.

But where was the mastectomy? Going back through the letters, I realized that she did have surgery in January 1946, which she evasively described it in a letter to her brother Roscoe’s widow as removing “one of those useless little lumps which sometimes form on the human body. They may be entirely harmless, or may be serious. This one proved to be quite harmless.”

I then realized that Cather’s death certificate had become a public record in 2017, seventy years after her death. Caroline Schimmel, who lives in Manhattan, was anxious to see her grandfather’s signature on Willa Cather’s death certificate, so she secured a scanned copy at the Office of Vital Records. On the death certificate, William Crawford White reported the facts: Cather had been diagnosed with breast cancer in December 1945, her left breast had been removed in January 1946, and although he listed a brain hemorrhage as the primary cause of her death, he also reported that at the time of her death the cancer had spread to her liver.

Cather has long been characterized as extremely private and even secretive, and certainly, Cather’s approach to her breast cancer seems to confirm this: she kept her diagnosis secret from even close family members, and Lewis, who survived Cather by twenty-five years, maintained silence about it after Cather’s death. In many accounts, Cather’s lesbian sexuality has been identified as her greatest secret.

However, she and Lewis lived together openly for nearly forty years, jointly leasing apartments in Greenwich Village and on Park Avenue. Indeed, one of the main contentions of my book is that their domestic partnership was not a secret. Still, Lewis often was and sometimes still is made over into Cather’s secretary (she wasn’t) rather than being recognized for what she was: a highly compensated professional woman with a demanding office job who was also Cather’s romantic partner and her editor.

There were many ways for lesbian couples to be in New York City in the 1920s.I have a great deal to say in my book about how Edith Lewis was made over and made invisible, including how the grave site in Jaffrey, New Hampshire, where she and Cather are buried together was misinterpreted (no, Edith Lewis was not buried at Willa Cather’s feet). More recently, I have returned to the one proper surviving photograph of the two women together, which was taken in Jaffrey in 1926, to think through the visibility of Cather and Lewis’s relationship in new ways. The photograph appears in my book without comment, but I have since identified the photographer and have placed it in time in relation to other events in Cather and Lewis’s lives.

In my book, I consider the tradition of the so-called Boston marriage in the 19th-century United States as a precedent for Cather and Lewis. A book about 19th-century England I read only after I finished my own, Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England (2007) by literary historian Sharon Marcus, has given me some new terminology to think about how Cather and Lewis functioned in the world as a couple, including in this photograph.

In her discussion of what she identifies as a socially recognized institution of “the female marriage” in Victorian England, Marcus draws a distinction between subcultures and networks. Looking at lesbian life from the perspective of the mid-20th century, we are accustomed to looking for lesbian subcultures (think the lesbian bar or the lesbian softball league). However, Marcus argues that couples in female marriages lived their lives as part of social networks, and while these networks often included other female couples, they also included straight married couples. Put another way, these lesbian couples were not part of a lesbian subculture.

One of the reasons that I think Cather and Lewis as a couple have seemed invisible as such or have seemed to have been closeted is that there was an emerging lesbian subculture in Greenwich Village, where they lived until 1927. In The Daring Life and Dangerous Times of Eve Adams (2021), Jonathan Ned Katz recovers a key figure in this Greenwich Village subculture. Adams operated one of the lesbian “tea rooms” in the Village (alcohol was served only in speakeasies during prohibition, so no lesbian bars), and in 1925, she published a book titled Lesbian Love.

As far as I have been able to determine, Lewis and Cather did not patronize establishments like Adams’s. It was not a matter, however, of their being in or out the closet (in fact, the closet as a metaphor for thinking about sexuality was a product of later Cold War culture). Rather, there were many ways for lesbian couples to be in New York City in the 1920s. As educated, economically independent professional women, they held their famous Friday teas at their apartment at 5 Bank Street, which embedded them in a mixed social network rather than a lesbian subculture.

On Grand Manan Island at the Whale Cove resort community, where Cather and Lewis began vacationing in 1922, they did function as part of a woman-only subculture. The Whale Cove group was founded in the early 20th century by three women who graduated from the Boston Normal School for Gymnastics, which trained women to be gym teachers. Through at least 1940, as far as I can tell, only women owned or rented at Whale Cove.

Nevertheless, it was not exclusively a lesbian community; it was more what I have come to think of as lesbian-ish. In addition to romantic couples, there were pairs of sisters, widowed mothers with their daughters, and nieces as guests (including Cather’s and Lewis’s nieces). As the women who owned property there died off and because they did not have children to inherit their cottages, the lesbian-ish history of this community was lost and denied by subsequent generations who turned it into a “family” resort.

In Jaffrey, New Hampshire, Cather and Lewis stayed at the Shattuck Inn. There, they were, as in Greenwich Village, part of a mixed network rather than a subculture. Lewis spent less time at Jaffrey than did Cather—after all, she had a salaried office job in Manhattan. Nevertheless, she spent more time there with Cather than has been recognized. The woman who took the photograph of them at Jaffrey in 1926 is identified in the source where I found it only as “Mrs. Josiah Wheelwright.”

It took some digging to recover the identity of this woman whom convention subsumed into her husband’s, but I found her. Lois Curtis Nelson was born and raised in Chicago, graduated from Radcliffe College in 1921, and in mid-September 1926, when Cather and Lewis and Nelson took the picture, she was engaged to Josiah Wheelwright of Boston and was spending time in New England with his parents.

In the photograph, Cather and Lewis are on the town common, with the Old Meeting House is visible behind them to the left. Earlier that summer, they had spent a month in the Southwest. First, they conducted research for Cather’s novel Death Comes for the Archbishop, which would be published in 1927, and then they spent a week in Santa Fe with Willa’s brother Roscoe, his wife Meta, and their three daughters.

After Lewis boarded a train to return to Manhattan, Cather had planned to spend time writing at Mabel Luhan’s compound in Taos, where she and Lewis had spent two weeks together the year before and where the idea for writing Death Comes for the Archbishop had originated. However, Cather was not happy in Taos—Mabel and her husband Tony Lujan were not there at the time–and New York City was too hot to write.

So in August, with no room available at the Shattuck Inn, Cather wrote to Marion MacDowell, asking to be accommodated at the MacDowell Colony, not far from Jaffrey in Peterboro. While Cather was at the MacDowell Colony, Edith Lewis went on her own to Grand Manan, where, on September 5, she purchased land at Whale Cove and made arrangements for the construction of their own cottage, which would be ready for them by the summer of 1928.

Lewis’ smile in the photograph says to me that she was feeling pleased with that purchase. I also suspect, however, that she was sad about the recent death of her father, who was buried in his family’s plot in a country graveyard in East Claremont, New Hampshire. He had died in California, where he lived with one of her sisters, in the middle of her time in Santa Fe with Cather—I would hazard a guess that she made a point of visiting his grave while she was in Jaffrey. In any event, there they are, a couple, enjoying an autumn day in public, and a young straight woman, who was about to get married, took a snapshot of them together.

Cather and Lewis would return to the Shattuck Inn together many times in future years. From the Shattuck Inn in 1936, Cather would write to Lewis the beautiful one surviving letter from which I took the title of my book. In this letter, written almost exactly ten years after the photograph was taken, Cather addressed her partner as “My darling Edith” and described the conjunction of Jupiter and Venus in the night sky:

One hour from now, I shall see a sight unparalleled—Jupiter and Venue both shining in the golden-rosy sky and both in the West; she not very far above the horizon, and he about mid-way between the zenith and the silvery lady planet. From 5:30 to 6:30 they are of a superb splendor—deepening in color every second, in a still daylight-sky guiltless of other stars, the moon not up and the sun gone down behind Gap mountain; those two above in the vault of heaven. It lasts so about an hour (did last night). Then the Lady, so silvery still, slips down into the clear rose colored glow to be near the departed sun, and imperial Jupiter hangs there alone. He goes down bout 8:30. Surely it reminds one of Dante’s “eternal wheels.” I can’t believe that all that majesty and all that beauty, those fated and unfailing appearances and exits, are something more than mathematics and horrible temperatures. If they are not, then we are the only wonderful things, because we can wonder.

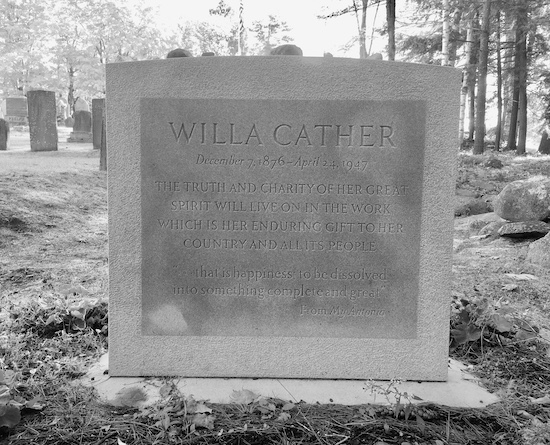

Ten years after Cather wrote this letter, Lewis would care for her partner in their Park Avenue apartment through two medically difficult years. When Cather died, Lewis would choose the Old Burying Ground, just out of range in the photograph, behind the church, as Cather’s final resting place. She would also design this beautiful headstone, featuring a quotation from Cather’s novel My Ántonia, as a semi-public memorial to her dead partner.

Cather left most of her assets, including books and papers, to Lewis, and she named her as her literary executor. In that capacity, Lewis commissioned a biography by English professor E.K. Brown and wrote her own memoir of Cather, Willa Cather Living (1953), in which she discreetly omitted any mention of Cather’s breast cancer.

Sharon Marcus’s observations about “female marriage” in Victorian Britain illuminate Cather and Lewis’s relationship in 20th-century America. Marcus points to many practices that marked women as “married” to each other: they lived together; they took care of each other’s bodies in life and death; they intermingled their assets and used wills to convey property, including papers, to each other after death; and when one of the women was a public figure, the surviving partner used those papers to publish a memoir or collection of letters. Cather and Lewis were, on all these counts, precisely like their predecessors in Victorian Britain.

While some would insist that we cannot know whether such relationships between women were sexual, Marcus argues that a search for explicit written evidence about sex is wrongheaded because it was precisely discretion about sexual matters that marked Victorian marriage, both in the cases of female couples and of legally married opposite sex couples. This kind of discretion concerning matters concerning the body also marked Cather’s approach to her cancer—perhaps she might have acknowledged and named cancer in some other part of the body, but not cancer of the breast.

Certainly, in some respects, Cather and Lewis were discreet about their relationship. In Cather’s letters, Lewis often appears, but she seldom assigns a label to her or to the relationship—she’s just “Miss Lewis” or “Edith” or the unnamed other half of the plural first person pronoun “we.” When Cather does use a label, as in her “Chance Meeting” essay the label she uses for Lewis is “friend.” She does not pretend, however, that Lewis is not there or that they do not live and travel together. The thing about which both Cather and Lewis were the most discreet was Cather’s breast cancer, not their relationship with one another.