Lolita is Nabokov: On the Parallel Histories of the Writer and His Most Famous Character

Monika Zgustova Explores Childhood Sexual Abuse and Its Aftermath, On and Off the Page

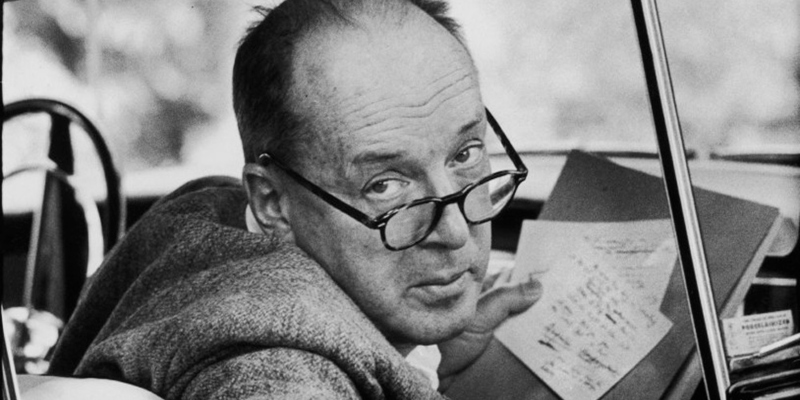

When I was conducting my research for my novel A Revolver to Carry at Night, I immersed myself in the correspondence, biographies, and works of Vera and Vladimir Nabokov’s biographies. It was in Nabokov’s poetic memoir, Speak, Memory, that I discovered the story that inspired Lolita, and began to understand Nabokov’s relationship with his novel and its subject matter.

Vladimir Nabokov’s parents used to spend their summer vacations in Vyra, in a mansion with a large garden on the outskirts of St. Petersburg. After one of those late, long, hearty lunches, so characteristic of wealthy Russians’ habits before the Revolution, the hosts and guests went out on the terrace for coffee. Vladimir, who in that spring of 1907 was eight years old, was looked after by his uncle Vasily Rukavishnikov, a diplomat. Rukavishnikov was also known as Ruka, which in Russian means “hand.” Uncle Ruka was a very elegant man who always wore a violet carnation in the lapel of his pearl-gray coat and liked to recite poems aloud.

When the diners went out onto the terrace, the uncle suggested to the boy that the two of them remain alone in the sunlit dining room. He sat the boy on his lap and caressed him gently, whispering playful and mischievous words in his ear; little Vladimir felt embarrassed. He was relieved when his father entered the dining room from the terrace. Vladimir realized that the father was annoyed with his brother-in-law because he sternly demanded that he go out with the others to the terrace. The boy was sent to his room.

That same evening the uncle came to little Vladimir’s room. He asked the boy to show him his butterfly collection and while they contemplated it together, the uncle tickled his face with his silky mustache and continued with his caresses and increasingly daring touching. These encounters were pleasant and unpleasant, tantalizing and disgusting at the same time. They lasted several years.

Since Lolita was published, readers around the world have wondered who the mysterious girl is, on whom or what experience Nabokov had based his character. While researching for my novel I found the evidence, which no one seems to have noticed before, that in this novel Nabokov was describing abuse of which he himself had been the victim as a child. In subchapter 3 of chapter three of Speak, Memory, Nabokov says:

Uncle Ruka appeared to me in my childhood to belong to a world of toys, gay picture books, and cherry trees laden with glossy black fruit […] When I was eight or nine, he would invariably take me upon his knee after lunch and (while two young footmen were clearing the table in the empty dining room) fondle me, with crooning sounds and fancy endearments, and I felt embarrassed for my uncle by the presence of the servants and relieved when my father called him from the veranda: “Basile, on vous attend.”

As Nabokov indicates indirectly but clearly enough in his memoir, these abusive games lasted three or four years.

When Vladimir was eleven or twelve, he confesses, one day he went to pick up his uncle at the railway station. Uncle Ruka was coming from abroad to spend the summer at his estate in Vyra, which adjoined the summer residence of Nabokov’s parents. Seeing him, Ruka said to the boy, “How sallow and plain [jaune et laid] you have become, my poor boy.” On Vladimir’s fifteenth birthday, the immensely rich Uncle Ruka announced to him in a somewhat old-fashioned French that he had made him his heir. Then he dismissed him: “And now you may go, l’audience est finie. Je n’ai plus rien à vous dire.”

Something similar happens in Lolita: at the end of the novel, after a desperate search, the kidnapper Humbert Humbert finds a grown-up Lolita, seventeen years old, married and pregnant. Her seducer finds her pale, freckled and emaciated and presents her with a large sum of money for her wedding. However, Lolita is unable to enjoy her sudden wealth because she dies in childbirth.

In a similar manner Nabokov was unable to enjoy his inheritance (which, according to him, “would amount nowadays to a couple of million dollars” as well as the estate of Rozhdestveno, next to Vyra, from his uncle), because when he was eighteen the Russian revolution caused the total devaluation of the ruble and, before going into exile, Nabokov lost everything. This was an episode in Nabokov’s life that intrigued me because I am an émigrée myself. Like Nabokov’s parents with Vladimir, who in his twenties sought exile in Western Europe after the October revolution, my parents escaped communism fleeing to the United States when I was sixteen. For this reason, I feel a strong kinship with Nabokov.

He made it clear for those who know how to read that he rejected the unworthy seducer of minors and that Lolita was a victim, like Nabokov himself.

Nabokov was obsessed with the idea of child abuse. He first wrote about it in The Sorcerer, a novel he later called “the first palpitation of Lolita,” but he was not entirely satisfied with it. After Lolita he returned to the topic of harassment and abuse in Pale Fire. In all three cases, Nabokov expressed his displeasure and rejection of the abuse committed against children.

It is possible that very few people, perhaps only the writer’s wife Véra, knew this secret because Nabokov wrote about it in Speak, Memory in a roundabout way. Véra was well aware that her husband liked women as much as he enjoyed butterflies. But, according to Katherine Reese Peebles, with whom Nabokov had a short love affair when he was a professor at Cornell University in the United States, he liked women and young women, but never adolescents or little girls like Lolita’s protagonist Humbert Humbert did.

Vladimir used the kidnapping of the little girl Sally Horner, a case which shook the country in the late forties. Day after day Nabokov searched the American newspapers for new revelations about Sally’s terrible vicissitudes in the hands of her kidnapper, in order to use them in his novel. Sarah Weinman has recently published the book The Real Lolita about the kidnapping of Sally Horner.

Over the decades criticism of Lolita has been heard from a feminist point of view. However, some of these critics do not seem to perceive all the nuances in the novel. Being the great work of art that it is, Lolita is written with absolute freedom and seeks to reflect the complexity of a certain type of human behavior.

The beginning of each chapter—“ladies and gentlemen of the jury”—clearly means that his readers are the judges of the kidnapper who is on trial. Nabokov never intended to write a pamphlet, although between the lines he made it clear for those who know how to read that he rejected the unworthy seducer of minors and that Lolita was a victim, like Nabokov himself.

__________________________________

A Revolver to Carry at Night by Monika Zgustova, translated by Julie Jones, is available from Other Press.

Monika Zgustova

Monika Zgustova is an award-winning author whose works have been published in more than ten languages. She was born in Prague and studied comparative literature in the United States (University of Illinois and University of Chicago). She then moved to Barcelona, where she writes for El País, The Nation, and CounterPunch, among others. As a translator of Czech and Russian literature into Spanish and Catalan—including the writing of Havel, Kundera, Hrabal, Hašek, Dostoyevsky, Akhmatova, Tsvetaeva, and Babel—Zgustova is credited with bringing major twentieth-century writers to Spain. Her book Dressed for a Dance in the Snow: Women’s Voices from the Gulag (Other Press, 2020) was a World Literature Today Notable Translation of the Year.