Locked Down in Denmark, Learning a Language and Finishing a Novel

Maria Adelmann on the Rewards of Endurance

I’d arrived in Denmark in February, on what was supposed to be a six-week trip to visit my partner. It rained almost every day that month—quite the weather for a country that it is often said to contain the happiest people on earth. I stayed inside, plodding through the novel I was writing. From my window, I watched intrepid Danes walk and bike by on the street below. They wore puffy long coats, rain-pants, full snowsuits. “There is no such thing as bad weather,” the Danes say, “only bad clothes.” On the rare occasion that the sun appeared, I ran outside, frantically chasing down patches of light in the cemetery, of all places, because the “happiest people on earth” use graveyards as parks.

March came and with it a global pandemic and a cancelled flight. The news was so terrible, the lockdown so mundane. Another flight was cancelled, then another. Eventually, I stopped rebooking. I just… stayed. I had made an international move with just a suitcase and a carry-on.

I was living in a new country, during a lockdown, and my life had whittled itself down to mainly one thing: the frustrating endeavor of writing a novel, sold along with my short story collection in a two-book deal. My greatest leaps toward integration were watching Nordic noir, eating pastries, and improving my biking, which was not nearly good enough for a country where rush hour looks like the Tour de France. Online, I watched people take up hobbies: herbs on windowsills, sourdough bread, jigsaw puzzles. I needed a hobby of my own. I signed up for an intensive Danish class, taking to it with the vigor of someone with no other extracurriculars. I nestled into bed each night with headphones and index cards, repeating phrases slowly and writing them down, trying to make sense of all of those ø’s, å’s, and æ’s.

One day in late summer, I found myself sprawled face-first on the pavement in a bike lane—it turned out you couldn’t just bike over a curb. By then, I’d already spent some two hundred hours studying Danish. Yet when a woman who’d been biking ahead of me stopped, presumably to ask me if I was okay, I couldn’t understand a word.

“Mine bukser er dårlige,” I tried, looking down at the only pair of jeans I’d packed those many months ago. “Jeg er god.” My pants are bad. I am good.

“Hvad?”

I sighed. “English?” I said, and she shifted seamlessly, as most Danes can.

Two. Hundred. Hours.

I was living in a new country, during a lockdown, and my life had whittled itself down to mainly one thing: the frustrating endeavor of writing a novel, sold along with my short story collection in a two-book deal.

With bloody palms and a bruised ego, I did a sad-sack spiral on the slow bike ride home, feeling like a failure. I wasn’t even a cool kind of failure, the self-sabotaging partier, the productive procrastinator, the lazy pot-smoker. When you don’t try, at least there’s always the possibility that you’re a secret genius.

I was the kind of failure who had discovered, fully and unequivocally, that she is not a secret genius, the kind of failure who practiced biking in the driveway of an old person’s home after each day of writing, who spent ten hours a week on Danish homework only to be lost in class, and, oh yeah, who had spent a year writing a novel that she now had to rewrite.

Kill your darlings? More like slash and burn.

My short story collection was soon to be published, but writing the novel was completely different. It’s not that the collection had been easy, just that I had written it piece by piece over so long, with no particular hope of having it published, that it never seemed, altogether, unwieldy or unmanageable. The novel, on the other hand, was overwhelming, the extended deadline ever-looming, and the more time and resources I sunk into it, the worse I felt about it and myself. Each morning before sitting down at the keyboard, I poured myself a cup a coffee and said, “Another day, another dollar.” Comedic pause. “Just kidding. Just another day.”

“A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step,” I’d told myself when I’d begun, going so far as to tack the quote above my desk. But, by year two, the quote seemed ridiculous. Starting? That was the easy part. I needed a different quote, one about how and why to continue a journey of an unknown number of miles with an unknown destination. If I ever finished the book, after all, it could bomb.

Like writing the novel, starting Danish had been simple. I just showed up and kept showing up. I felt joy when language that had previously been mysterious became intelligible: when I understood “receipt?” at the checkout, when I could read the cooking instructions on a package of food, when I could point out a discrepancy between the Danish dialogue and the English subtitles.

But now I wondered what I really had to show for all the time I’d invested. Sure, I’d progressed, but wasn’t it all just a party trick until I could actually communicate? And when would that be? There was so much left to learn, no end in sight.

I was the kind of failure who had discovered, fully and unequivocally, that she is not a secret genius, the kind of failure who practiced biking in the driveway of an old person’s home after each day of writing.

“Maybe I should stop trying things I am clearly failing at,” I said to my partner that night.

“You don’t fail at a marathon when you’re still up and running on mile 13,” he said.

“But I suck at Danish,” I said. “And the novel…”

He reminded me that he knew plenty of people who’d lived here for years and hadn’t bothered to learn the language, and that there were people who said they always wanted to write a novel who never did.

“Functionally, those people are the same as me,” I said. “We both can’t understand Danish and we both haven’t written a novel.”

“I don’t know why you’re always so shocked that you’re not finished with something that you’re obviously in the middle of,” he said.

“What if I’m always in the middle of it?” I asked.

“I don’t know. Maybe you’ll still get something out of it,” he said. “Maybe it’s the chance you take.”

*

In December, Copenhagen gets about a half hour of sunlight per day. I’ve lived here for almost a year. Between writing and practicing Danish, I take daily walks in a cemetery in the cold rainy dark.

Like writing the novel, starting Danish had been simple. I just showed up and kept showing up. I felt joy when language that had previously been mysterious became intelligible.

It’s a beautiful graveyard: yellow-walled, with willow trees and winding paths, a green space where people spread out on blankets in the summer and drink beer. I read the gravestones: grocer, researcher, loving uncle. Among them, HC Andersen and Søren Kirkegaard, too. I don’t know much about the latter, but I tacked a new quote from him above my desk: “Dersom den, der skal handle, vil bedømme sig selv efter Udfaldet, saa kommer han aldrig til at begynde.” (“If anyone on the verge of action should judge himself according to the outcome, he would never begin.”)

I’ve read that Danes are the happiest people on earth in part because they have low expectations—thus, few disappointments, and sometimes a nice surprise. But I wonder if it’s not so much low expectations as realistic expectations. You don’t wait for sun. You take Vitamin D. You get dressed. You go outside. You show up.

You sit down at the keyboard. You write.

The other day, I was walking through the graveyard with a friend. There was a steady, misty rain, and we’d bundled up in raincoats and rain pants. I’d met her in Danish class—that alone made it worth it, to have a new friend in a new country during a pandemic. She’d learned English as an adult, and I asked her if there was a moment when it just “clicked.”

“No,” she said. “First, I could understand part of what people were saying and then more of it.”

“And now all of it,” I said.

“No,” she said, laughing. “Just always more than before.”

The sun appeared suddenly—we hadn’t seen it in many days, and she and I stopped in the nearest stream of light and continued to talk. I looked out across the graveyard, and saw something astounding: everyone had stopped, a whole graveyard full of people had found the nearest patch of sun and were standing it: on muddy paths, between gravestones, next to tombs. Then a cloud covered the sun. “That was so nice,” I said, and we put one foot in front of the other and continued on.

__________________________________

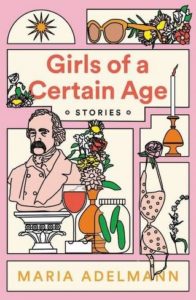

Girls of a Certain Age by Maria Adelmann is available now via Little Brown and Company.

Maria Adelmann

Maria Adelmann's work has been published by Tin House, n+1, The Threepenny Review, Indiana Review, Epoch, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, and others. She has received fellowships from Cornell University and The University of Virginia, where she earned her BA and MFA respectively. Maria has had quite a few jobs (visual merchandiser, instructor, hotel reviewer) in quite a few cities (New York, Baltimore, Copenhagen) and once on a ship. She enjoys learning new crafts and letting personal projects take over her life. You can visit her online at mariaink.com or on Twitter and Instagram @ink176.