I.

This story starts when my parents drop me off at my uncle Jim’s house, on the way to the hospital where my little sister is about to be born. I am six years old.

Uncle Jim is married to a woman named Rhonda, whose hobby is crochet. No, not “hobby,” exactly: her crocheting is a compulsion, perhaps some kind of illness. Rhonda crochets cozies not only for the extra toilet paper rolls, as I’ve seen in some of my friends’ bathrooms, but also for the phone and the phone book and the dog and my uncle’s guns and both of their toothbrushes. This cozying does not make the objects look cozier; it makes them look ashamed.

I sit all day on the sofa, the crochet pattern imprinting itself onto my sweaty legs, watching an I Dream of Jeannie marathon and waiting for my parents to show up and take me home. I expect this to happen quickly—within, say, an hour. No one has explained to me how long babies take to come; I have the vague idea that they just spring out, like a Pop-Tart from the toaster. Also no one has explained to me that it’s way too early, that the baby is not supposed to come for two more months.

When my parents have not shown up or called by late afternoon, I begin to suspect that they are not coming back at all. When eight o’clock—my bedtime—arrives, I know with certainty that they have taken the new baby home to replace me and that I will remain with Jim and Rhonda forever. I see myself sitting here on the lumpy loveseat, becoming another permanent fixture of the house. Rhonda will crochet a cozy to encase me from head to toe, so that you can barely make out the lumpy shape of my body; I’ll breathe through a woolly woven web, and will only be able to see the world in pieces, through the constellation of small apertures between the yarn.

That night in the cramped guest bedroom, fearful and unable to sleep, I create the Little Sister. I have invented characters in my mind before, fairies and pirates and things like that. This is different. I do not intend to create anything. I only try to picture the shape of this sister I have desired and already lost, this soft human curve of abandonment, and the pressure of my need turns her real, and suddenly there she is, lying beside me on the crochet-blanket-covered bed, looking up at me with blue eyes and kicking her fat little legs. She looks like a normal baby in every way except the color of her skin—a warm, translucent gold. She smells sweet and powdery. I take her onto my lap and look down at her. She has real softness, real weight. She is a beautiful baby but I know that this is not how babies are supposed to come into the world, and her presence gives me a dark feeling. I carry her over to my My Little Pony backpack and zip her up inside. She just barely fits. Then I return to the bed and instantly fall asleep.

“Rhonda crochets cozies not only for the extra toilet paper rolls, as I’ve seen in some of my friends’ bathrooms, but also for the phone and the phone book and the dog and my uncle’s guns and both of their toothbrushes. This cozying does not make the objects look cozier; it makes them look ashamed.”

I awake early the next morning, to my father pulling me up off the bed by my armpits. It has been a thin, sour, uncomfortable sleep; I am so dizzy with relief to see him that I throw my arms around his neck and weep. He grunts to me and speaks a few gruff words to Jim and Rhonda. Then he carries me out to the car, throws the backpack in the back seat, and drives me home.

But my mother is not at home, and neither is the baby, because there is no baby. There was a baby, for a minute, but then it just went out. That’s the phrase my father uses: “It just went out.” At first I think he means that the baby got up and walked away. It takes me a minute to realize that he means the baby is dead.

I have not lost my parents, not in the way I thought I would. But I understand that things are different now. When I unzip my backpack in my bedroom that night, the Little Sister is still alive. She blinks up at me like nothing has happened, like we are guilty of nothing. In the middle of the night I sneak out of bed, take my dad’s shovel from the garage, and bury her beneath the oak tree in the backyard. She does not complain or cry, but still I look away from her as I work, not wanting to watch the dirt fall onto her blue wide-open eyes.

II.

Two years later, my parents sit me down and explain that from now on they will be living in different places. This announcement puzzles me because my dad already does not live with us. He has been on a “business trip to Arizona” since my eighth birthday. This is the first time I have seen him since then. Even before he left, I had not exactly thought of him as living with us, because I no longer exactly thought of him as living. He would fall asleep in strange places, like the backyard or the kitchen floor; during his brief moments of wakefulness he would talk too loudly and hug me too hard, like a distant relative, or the Santa Claus at the mall.

“We still love you,” says my mother. “I mean, I still do.”

“Some people,” says my father, “are just not cut out to be fathers. I might have made a good uncle. This has been a whole different ball game.” He leans forward, puts his elbows on his knees. “That is how I want you to think of me,” he says.

“As a ball game?” I ask.

“No,” he says. “As an uncle.”

“I’m getting us a new apartment in town,” says my mother. “It’s next door to the Denny’s. We’ll be closer to school. And Dad will have his own apartment too.”

“Why can’t we stay in this house?” I ask.

“Don’t beat yourself up about this,” says my father. “It’s not your fault.”

It’s an answer, but not to the question I’ve asked.

The night before we move, I sneak out to the backyard once again. Grass has grown over the Little Sister’s shallow grave, but the spot is still visible. I don’t exactly want to see her again, but the idea of leaving her there beneath the earth fills me with loneliness and panic.

I take the shovel and dig her up. She is still alive, still glowing faintly. She stirs, blinks the dirt off her eyelids, and looks at me. Her eyes glisten wetly, as if she has just been crying or is just about to, but she doesn’t make a sound. I notice that she is bigger now, toddler-sized, with a round belly and plump wrists and a thick head of white-blond hair. Apparently her burial has not stopped her from growing. Apparently she is like a plant: pushed down into the earth, fattened like a root, nourished by darkness.

__________________________________

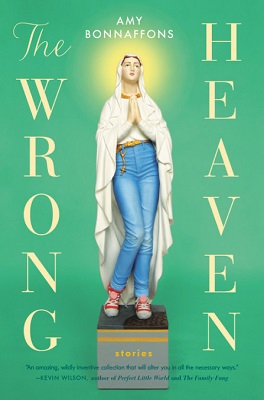

From The Wrong Heaven. Used with permission of Little, Brown, and Company. Copyright © 2018 by Amy Bonnaffons.