Literary Alchemy: On Fusing Research and Film Techniques to Write a Novel

How Mo Ogrodnik Depicts Violence Against Women from Multiple Perspectives

The spark for my novel, Gulf, began when I was living in Abu Dhabi and working for NYU. A friend of mine who was the Director of Equality Now, a global women’s rights organization, enlisted my help to find a lawyer for a group of South Asian women who had collectively murdered their trafficker.

Wanting to learn about the case, online research led me into a labyrinth of police reports and articles recounting violence between female employers and their domestic workers. The intimacy of the violence stayed with me. The tools of abuse were often household items: irons, boiling water, electrical cords, kitchen knives, Clorox, and fire.

Patterns emerged and I began to see these crimes as expressions of larger political structures (patriarchy, migration, and labor) being enacted by women in domestic and private spaces.

Questions began to consume me: What is the relationship between violence and freedom? How does a woman, who has never exhibited violent behavior, evolve to commit these acts?

These questions led me to the broader region: women setting themselves on fire in Afghanistan and Iraq, women policing other women on the streets of Raqqa, and the larger legacy of American violence and erasure of which I was a part. As James Baldwin wrote, “When you’re writing, you’re trying to find out something which you don’t know. The whole language of writing for me is finding out what you don’t want to know, what you don’t want to find out. But something forces you to anyway.”

My way of “knowing” was through research—travel grants brought me to Ethiopia where I interviewed girls who had been illegally trafficked into the Gulf via Yemen, and to the Philippines where I spent time in a domestic worker training center with forty women being deployed to Saudi Arabia. I read extensively about women who’d joined the female morality police in Iraq and Syria, about the history of the U.S. presence in the region, and the deaths caused by American drone strikes on civilian populations.

How research alchemizes into a novel is mysterious, but images anchor my process due to my background in documentary and narrative filmmaking, images gathered online, from my own archive, from museums, and art books. I was inspired by writers who combine text and image in their work: Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, Maria Kalman’s The Principles of Uncertainty, W.G, Sebald, and Duane Michals.

For a long time, xeroxed photographs populated the middle section of the novel—they were one of the last things to go.

Filmmaking has taught me a great deal about structure, but the novel offered the opportunity to explore narrative in more expansive ways. Once I knew that I had five female characters who were thematically linked, I began to consider a repeating quintet pattern. I’d often imagine the novel as a slide carousel with each woman’s chapter emerging onto the screen and then disappearing. In cinema, meaning comes from the cut, the unexpected link between images, and I wanted the reader to consider the inner lives of these women, to feel the undercurrents of connection on an emotional and psychological level rather than plot.

I was interested in the idea of the Gulf both as a physical location but also the gulf between women and the chasms within ourselves.

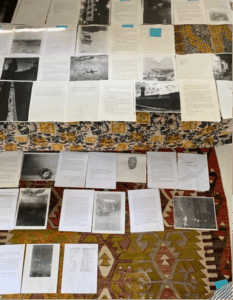

During my writing process, I took many writing and art classes. During a workshop at Aperture, I re-mixed images on the floor. My process bridges documentary and narrative strategies. I treat the photographs as raw footage that I’ve gathered in the field and begin an intuitive process of finding clusters of connection based on aesthetic considerations, subject matter, or a feeling.

During this process, I’m burrowing into a kind of psychological/emotional knowing where scenes begin to form, but I’m unsure where they’ll live. Narrative imaginings and ideas for scenes begin to fill the gaps.

The power of the image to hold implicit meaning exists in poetry, prose, cinema, and photography. Throughout the writing and research process, I’m looked for image systems to carry the throughlines of the book.

The research in Ethiopia led me to the meskel festival that celebrates the discovery of the last piece of the cross with burning demeras. These fire displays connected to the burning of palm fronds on date farms in Saudi Arabia and female self-immolation as political protest.

One character sucks on the sour pith of an orange while crossing the Red Sea while another peels a clementine in her dark basement room. A ring once belonging to a Yemeni girl killed by an American drone strike gets passed to the Ethiopian girl who leaves it as a parting gift to an American teen living in Abu Dhabi. Linking characters through objects and images creates unlikely and unspoken connections that can percolate within the reader and create a spectral presence.

But at a certain point, I had to leave the images and my visual making process behind and face the starkness of words on a page, the work of building a world sentence by sentence. Unlike screenplays which are an invitation to collaborate and a blueprint for production, a novel is a final form even it lives across different mediums later.

Many novels migrate to film and television, but there’s also the remarkable Museum of Innocence in Istanbul that is based on Pamuk’s book of the same title that displays objects and installations from the central love story and is a remarkable example of narrative taking different forms across different platforms. But regardless of the possible forms prose can take, the work of words on a page remains.

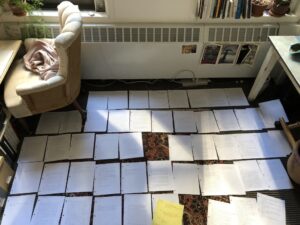

Once I had written scenes, I’d lay them out on the floor in order to feel the “throw” from one woman’s story into the next. I’d then edit the scenes like a film sequence, paying attention to what image was ending a chapter and what it was “throwing” towards.

This is an instinctual process of building torque or as Maggie Nelson calls it, “a thickening.” Socrates refers to this as “the movement of the spirit.”

I’ve come to hate language like “raise the stakes” or “conflict.” These terms alienate me from the story and feel akin to an amateur director telling an actor to “do it faster”—it’s what’s called “result” directing.

*

Gulf grew out of my time living and working in Abu Dhabi, my interest in the transnational landscape and how different forms of female violence express larger issues of labor, migration, and global histories. I was interested in the idea of the Gulf both as a physical location but also the gulf between women and the chasms within ourselves.

But even as I write this, I know how useless these “ideas” are unless they’re grounded in characters, settings, and situations; research and images sparked my imagination and led me into the innermost rooms of my characters.

The experience of seeing a film in a theater with an audience creates the feeling of participating in a collective dream. But picking up a book at a tag sale, from a library shelf, or a table display and engaging with another person’s consciousness through abstract marks on a page is one of the most intimate and profound encounters available to us as a species; prose is a highly interactive art form, activated by the reader’s mind, a mind that uploads the writer’s words on the page and translates them into their own images and meaning, culminating in a sublime kind of contact.

__________________________

Gulf by Mo Ogrodnik is available via Summit Books.

Mo Ogrodnik

Mo Ogrodnik is the author of Gulf. She is a filmmaker, writer, and professor in the film department at NYU. She was the associate dean of the arts for NYU in Abu Dhabi and the director of FIND, a creative lab exploring the transnational heritage of the UAE. She’s served as a mentor for the Sundance Labs in Jordan and received fellowships from Yaddo and MacDowell.