Listen to the Firespitters: Seven Poetry Books to Read This February

Christopher Spaide Recommends Ali Cobby Eckermann, Steven Duong, Oluwaseun Olayiwola and More

It’s a new year, which means it’s yet another occasion to be the same old unbudgeable person as last year while grumbling to oneself, new year, new me. (I can’t read that phrase without thinking of fellow grumbler Wallace Stevens and his sneering poem “The Motive for Metaphor,” which diagnoses that motive as the evasiveness of a poet “Desiring the exhilarations of changes,” “shrinking” from confronting his stagnant self, “The vital, arrogant, fatal, dominant X.”)

It doesn’t have quite the same ring, but a new year does mean new poetry: this year, that includes debut books from Steven Duong and Oluwaseun Olayiwola, Juliana Spahr’s first collection of poetry since 2015’s That Winter the Wolf Came, and the American publications of books from the UK (Isabel Galleymore’s Baby Schema) and Australia (Ali Cobby Eckermann’s She Is the Earth). February also brings a publication anticipated for over a decade: Firespitter: The Collected Poems of Jayne Cortez, which gathers poems from 1969’s Pissstained Stairs and the Monkey Man’s Wares (what a title) to 2012, the year of Cortez’s death. New poetry, new poets, beloved poets newly collected: the old me will take all of it.

*

Ali Cobby Eckermann, She Is the Earth

(Flood Editions, January 6)

She Is the Earth, the latest volume by the Aboriginal Australian poet Ali Cobby Eckermann, pairs paradoxical virtues: breadth and sparseness, naturalist precision and vaporous dreaminess. Stand back, and the book’s narrative contours might suggest a visionary quest, a chronicle of mothers and daughters, or a do-over at a creation myth: “and so it begins / a new beginning / not quite genesis,” reads the book’s first page. Listen close to any one page, and She Is the Earth instead sounds like a songbook, written largely in two-beat lines and incantatory couplets, strung together by parallelism and repetition: “dreams appear / vibrant in the night // the dreams reappear / viscous in the day // dreams are a promise / dreams are a compass.”

Steven Duong, At the End of the World There Is a Pond

(W.W. Norton, January 14)

Steven Duong’s debut collection introduces not only a poet but a fiction writer chipping away at his first novel, a tattoo artist, a freshwater-fish aficionado, a postcard-happy world-traveler, and a craftsman of fabulous, fabulist titles. One pole of Duong’s artistry is uncontainable abandon, a virtue shared by the mythical Icarus, fish jumping free from their aquaria, and the fusion-powered voice he cranks up in “Ode to Playboi Carti in the Year of the Dog”: “When I kick up the treble, something in your voice cracks / like a sun ten seconds from going red dwarf, from cracking // the sky open like a pint of your favorite.” The other pole is a painstaking formalism, a commitment to steadfastness and sobriety, as in his sonnets, which boast tattoo-precise lines and the willful sturdiness of gravestones: “I am granite: a hard summit / of devotion, losing ground each year to acid / rain & soil erosion. Though I am stone, // I am not unfeeling.”

Oluwaseun Olayiwola, Strange Beach

(Soft Skull, January 21)

“How beautiful // you have been and are // giving your whole life to a pointless competition—”: so concludes the opening poem of Strange Beach, the debut book by Oluwaseun Olayiwola, a Nigerian American poet, critic, and choreographer based in London. In line after line, Olayiwola strikes on phrases that counterbalance multiple meanings, each with its own semantic rightness and visceral tug. Take that beautiful yet pointless “competition”: it may refer to a life devoted to art (poetry, criticism, dance) or else the cross purposes of desire, with its “inseparability of light / and dark.” The same poem describes a “transatlantic voyage / spread on the page / like an oil spill,” which could suggest Olayiwola’s move to England, or possibly the historical disasters of the Middle Passage (as in Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, the source of Olayiwola’s title). Strange Beach introduces a poet of aphoristic clarity and moment-by-moment drama, whose strongest poems often end on an em-dash, as though startling themselves into silence: “Immeasurable beauty / is immeasurable precisely / until it’s gone—.”

Ange Mlinko, Foxglovewise

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, January 28)

Ange Mlinko’s seventh collection takes after the foxglove, a flower of hardy glamor and season-to-season inconsistency, as in the Louise Glück lines that Mlinko plucks for her epigraph: “first springing up / a pink spike on the slope behind the daisies, / and the next year, purple in the rose garden.” Dedicated to the memory of her late parents, Foxglovewise catalogues several years of metamorphoses and transplantings: an audiobook of The Iliad keens in a Scottish cemetery, “Ice storms shatter and varnish the South,” and an enchanted imagination stages Shakespeare’s The Tempest underwater: “As if / a production of Ariel and Prospero / were pending in the ocean’s void, / the amphitheater of the asteroid.” Constancy arrives, when it does, in art and our dedication to it—evidenced in the hands of Mlinko’s guitar-playing son and “the tenderness each callused tip affirms”—or in nature, playing variations on old themes. Take her ode to “Radishes”: once tongue-numbingly “peppery” yet “so much milder now,” they’re still “good to gnaw,” especially “late in the year, when the knife is duller.”

Isabel Galleymore, Baby Schema

(Carcanet Press, January 31)

Published last year in the UK and just now in the US, Isabel Galleymore’s second full-length collection Baby Schema scrutinizes human hierarchies and imperiled ecosystems through the pinhole apertures of the cute, the oh-so-precious, the vulnerably itty-bitty. “The kittens are so adorable I could die!” one poem repeats, the emphasis incrementally shifting from so adorable to I could die! Moments after looking at the natural world’s fuzziest ambassadors, Galleymore is already looking back at herself, at the desires underlying any looks shared between species. “Making eye-contact with a squirrel / for a second or three too long, / I find myself still waiting / for nature to wave back,” opens the book’s most exploratory sequence. Galleymore, a whiz at changing scales in the span of a flipped page or enjambed line, titles the sequence after a global capital of people-sized, people-loving animals: “Disneyland.”

Juliana Spahr, Ars Poeticas

(Wesleyan University Press, February 4)

Juliana Spahr’s Ars Poeticas sticks an -s onto the title of antiquity’s best-known poem-about-poetry, Horace’s Ars Poetica (Latin, “the art of poetry”). There isn’t one meditation on the art of poetry here: there are seven, by turns digressive and recursive, self-questioning and self-devouring, with titles like “Ars Poetica 1: Coral” and “Ars Poetica 4: Bison.” The book’s multiplicity reflects Spahr’s experimental temperament as well as a planetary biodiversity thinning out thanks to capitalism, the source of “this predicament we are in / where there is only one way out.” “Ars Poetica 7: Acknowledgements,” the book’s closing piece, does double duty, transforming the familiar acknowledgments section into an essay on solitude and solidarity, in action and in poetry: “I never go it alone. I’m not sure anyone can. That’s my point. // That’s my point. There are always friends and police.”

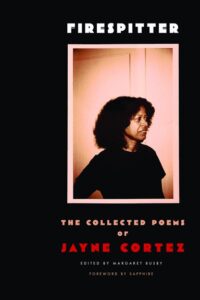

Jayne Cortez, Firespitter: The Collected Poems of Jayne Cortez, edited by Margaret Busby, foreword by Sapphire

(Nightboat Books, February 25)

“how long has this jayne, this breathtaking jayne cortez been gone?” asked Evie Shockley in a poem in memory of Jayne Cortez (1934–2012), the much-missed Black American poet, performer, activist, and publisher. Shockley was riffing and rhyming on Cortez’s virtuosic elegy “How Long Has Trane Been Gone” (1969), which pays tribute to the saxophonist John Coltrane in sheets of verbal sound, “John Coltrane who had the whole of / life wrapped up in B flat.” That poem, Cortez’s most widely anthologized and recorded, now appears alongside hundreds of others in Firespitter: The Collected Poem of Jayne Cortez. The collection’s title, a fittingly superheroic name for Cortez herself, is one she shared with her band, The Firespitters: “listen to the Firespitters / a caravan of / Firespitters / spitting into the river of asbestos /…/ we’re here.”

Christopher Spaide

Christopher Spaide is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Southern Mississippi. His academic writing on modern and contemporary poetry (as well as music and comics) appears in American Literary History, The Cambridge Quarterly, College Literature, Contemporary Literature, ELH, The Wallace Stevens Journal, and several edited collections. His essays and reviews and his poems appear in The Boston Globe, Boston Review, Lana Turner, The Nation, The New Yorker, Ploughshares, Poetry, Slate, and The Yale Review, and he has been a poetry columnist for the Poetry Foundation and LitHub. He has received fellowships from the Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry at Emory University, the Harvard Society of Fellows, the James Merrill House, and the Keasbey Foundation; for his academic writing and criticism, he has received prizes from Post45 and The Sewanee Review. Currently, he serves as the Secretary for The Wallace Stevens Society. He is the literary executor for Helen Vendler.