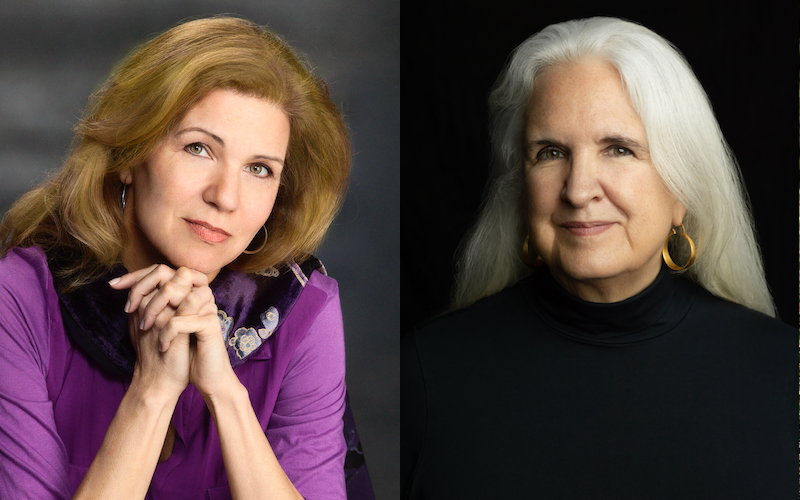

Lisa Gornick and Alice Elliott Dark on Altered States of Consciousness and Our (More than Five) Senses

The Authors of Ana Turns and Fellowship Point in Conversation

Lisa Gornick and Alice Elliott Dark met a dozen years ago through the Montclair Writers Group, a group of women writers who have gathered regularly over the past quarter century to support one another’s work.

As is the case with many writers, Lisa and Alice grew up with the practice of writing as a central part of their identities. Recently they began to email back and forth about how their writing practices had developed over time. They wondered what it had meant to the other to have lived for decades with reading and writing so central to their days.

*

Lisa Gornick: Alice, we were both passionate child readers and, not long after, child writers—the two entwined as the inhalation and exhalation of breath. Like you, I began with poems. I still recall the awareness of something magical afoot in those early efforts to transform what was confusing and murky or painful or dull into something crafted and streaked with light.

The world, I sensed, had many levels: there were the events skating over the surface and then the connections you might discover beneath. There was the deadening blandness of suburban middle school—lockers and worksheets and jarring bells—and then the momentary glimpses of a midsummer’s night enchantment in the flickering light of a forbidden cigarette under a magnolia tree; of the buried desires of a friend’s father as he ate his five o’clock dinner in his shirtsleeves and tie.

Can you tell me how and when you developed the desire to be a writer?

Alice Elliott Dark: I did start as a child. I wanted to capture the feeling that books gave me, and that had to do with making a book as much as it did with reading one. I copied the ideas of books I loved—my first fan fiction—and wrote illustrated novels about wise talking bears and big families having adventures. As a teen I got more serious about it, and wrote lots of poems, and position papers for the school paper. Smash the dress code! Get rid of grades!

I was deeply attracted to mysticism and altered states of consciousness and wrote in a version of an ecstatic state, in the middle of the night. I wanted to connect with something outside of myself through writing. I vibed to stories of astrophysicists seeking contact with intelligences in outer space. (Later, The Dancing Wu-Li Masters was another favorite, mind-blowing book.)

In college I stopped writing, believing that people like me weren’t real writers. Many artists speak of making the leap from never me to why not me—I did too, eventually. I didn’t have the idea that I wanted to be a writer until after college, when I found I was too shy to apply for anything but very unassuming jobs. In the vacuum, poetry came roaring back.

I was deeply attracted to mysticism and altered states of consciousness and wrote in a version of an ecstatic state, in the middle of the night.

How did you not put your writing aside during the early stages of development, when most people stop in favor of more lucrative or immediately rewarding occupations?

LKG: I grew up in an intellectual family, where no one talked about work being lucrative. What mattered was that work have meaning. The idea of an occupation was not on my mind—though I always assumed that I had to support myself and my taste for adventure.

By the time I turned eighteen, I’d worked as a cashier at Dunkin Donuts, as a research assistant for a guy with a stash of Victorian pornography and some shady financial dealings that landed him in federal prison, as the graveyard shift waitress at a diner renowned for occasional gunfire. My first year of college, I took a dazzling array of impractical classes: Buddhist philosophy, modern dance, a poetry workshop.

The workshop was all that I really cared about. We were given assignments to write in various classic forms, and for the first time I received feedback on my writing. But it was also the era of the glamorous suicidal poetesses—Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton—and with my consciousness so porous and my family having taken a turn into chaos, not a good time for me to spend countless hours alone, tapping out iambic pentameter and laboring in the basement recesses of an art library on the tenth draft of a poem.

Hungry for time away from the manicured lawns of my college, I signed up for a tutoring job at a nearby prison. My ex-con supervisor invited me to sit in on a group he ran. It was my introduction to psychotherapy and I was immediately smitten. The men in the group were telling stories, stories through which they could see themselves—not very different from what I did with my poems. Listening to their sometimes tragic, sometimes soulful, sometimes humorous tales, I envisioned a life in which I might both write (never expecting it would yield enough money to support myself) and work as a therapist.

I’d like to return to your mention of altered states of consciousness. We both came of age in the wake of the sixties, a time when drug experiences and new age practices were seen as potential pathways to enlightenment. Can you say more about how this thread has played out in your writing life?

AED: I was influenced by the ideas floating around in the ether, Aldous Huxley’s Doors of Perception, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the writings of Meister Eckhart and Teresa of Ávila, the Seth books by Jane Roberts and the shamanic adventures of Carlos Casteneda. I devoured their writings and was fascinated by worlds beyond the five senses. I craved those enlightenment experiences, and tried to get there by meditating, fasting (the era of parents without helicopters), and writing.

I didn’t revise, but waited until I had a poem or article fully formed in my mind and then transcribed it. It was dramatic—black candles, sealing wax, a whole occult atmosphere existed in my bedroom after midnight.

But I was also after the writing, and was struck that many mystics—excellent writers—made it clear they couldn’t put their experiences into words. The best they could do was to write around them. I began to pay attention to my own mind in a different way, noticing that I passed through states and feelings that I didn’t name. They were just there, shimmering, as I went through the day.

Then I noticed that when I spoke, or wrote, words felt like only a thin approximation of what was happening inside of me, and presumably inside everyone. Words were blunt instruments until they were attended to. It wouldn’t be enough to continue writing out of my version of ecstatic states. I wasn’t William Blake! I was a girl in a suburban bedroom who loved the Romantic poets and Sylvia Plath and Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, mystical writers who also knew how to make language embody meaning in their writing. (Bruce Springsteen said it well—”I got this guitar and I learned how to make her talk.”) I wanted to learn how to make language talk beyond the shorthand I got by with, while at the same time continuing to cultivate a place inside that was more untethered than my personality.

What inspired you to shift from poetry to prose?

LKG: What a gorgeous depiction of your early awareness that there is more to the world than we perceive with our five senses.

As a child, I had a strange sense of biding my time, stuck for the most part in that surface reality, waiting until I could strike out to create my own life—a life with more color and texture that would be worthy of being written about! At eighteen, I moved to Paris, living in a garret chambre de bonne. I spent my days as an au pair for the ill-behaved children of an elegant concert pianist, who instructed me on how a French woman dresses, and my evenings with various boyfriends—a Communist factory worker, a Polish photographer—while I saved up enough money to travel from Crete to Marrakech. Of course, I read Stendhal and Anais Nin and Henry Miller and Paul Bowles and of course I kept voluminous journals—never considering those pages to be my creative work.

My first foray into fiction came the year before I started graduate school, when I decided to teach myself to compose at the typewriter. I’d assumed that I’d continue my journal entries, but somehow with this new modality, the entries broke free and morphed into scenes that began to approximate stories.

It was the early eighties, an era of renaissance for that form. I gobbled up collections by Ann Beatty and Raymond Carver and Jayne Anne Phillips and Bobbie Ann for the precision and economy of their work. I joined a workshop run by Gordon Lish, infamous for precepts such as the writer, as god of the page, must never use their power to skewer others; the writer must take the reader by the hand, never confusing or condescending. It would be nearly a decade later, at which point my stories were bursting at the seams, before I would try my hand at a novel.

How about you? When and how did you make the shift from poetry to short stories? And when did you begin to develop a writing discipline as opposed to relying on those midnight, candle-lit ecstatic states?

AED: Like every woman writer I know, I have struggled to make time for my writing. I won’t even go into all that weighs against doing it; everyone knows. It is no accident that I was able to settle into working on a big novel, Fellowship Point, after my son had been out of the house for a year. I’d published a novel eight years earlier and tried two in between, and I couldn’t figure them out. They sit in plastic bins in my basement.

I was also after the writing, and was struck that many mystics—excellent writers—made it clear they couldn’t put their experiences into words. The best they could do was to write around them.

It wasn’t only time; it was mental space. When my son was born, he took over my brain and I thought of him always. He could tell if he weren’t foremost in my mind, and wanted me back. That was a conflict, as I knew it would be. Such is life. Such was I. Teaching also takes up a huge amount of mental space.

It has taken me a long time to sort through my writing/life problems, and I’m not done yet. I have arrived at a writing method that works reliably. I write before I do anything else, and I stop when my attention lags. Ninety minutes of writing this way is worth four hours of agitation, doubt, interruption. It’s very much the way I first wrote, except in the morning rather than the middle of the night, and without the spooky overlay. For revising, I work more hours, and then don’t mind distractions; I check my email, read. It’s fine.

My husband is extremely knowledgeable about fiction but I rely on him for encouragement above all, and that works. I have friends, including you, Lisa, who gave me great notes on Fellowship Point. My son, also a writer, is my top reader, and my agent has been insightful and helpful to me for years.

I do my best to support my friends and students. Knowing I have my hour or two early in the day makes fulfilling the needs of others possible without resentment. Sometimes I need to retreat; I love residencies for that. They are not as impermeable as they used to be but they’re still out of this world marvelous places that deserve all the support they can get. They offer artists many things, above all the chance to go deep and do better.

My greatest support is books. I have my favorites, and my favorite movies, and return to them over and over, not so much to learn as to settle down. I teach a class called Literary Fan Fiction where we look at conversations that take place in the form of stories and novels, often traversing the barrier of death. When I read I am always looking through the text, imagining the author’s handwriting or picking up their mood.

Lisa, we started talking about how writing has changed us but quickly realized it has been the organizing principle of our lives, so let me ask: what has that meant for you over time?

LKG: Oh my, Alice: you’ve found the exact idea—the organizing principle of our lives. I also work best in the morning hours–when my mind is fresh from sleep and close to dreams, before the pull of family life and the static of emails—but I’ve learned to accept that there are times when others’ schedules should come first and I have to bend.

Those imperfect not-first-thing hours are imperfect, but as long as I have quiet (construction earmuffs help in a pinch), I can now find my focus when I sit in my chair with my yellow shawl across the back, at my desk with the rose inside a glass paperweight and the handmade mug filled with my coffee always set up the night before, and the books that speak to what I’m working on nearby.

The organizing principle: Writing has become my meditation. When I’m at my desk and absorbed in finding the connection between inchoate thoughts and feelings and words ribboning across the screen, everything else drops away. I’m not worried about my ninety-four-year-old mother and her hearing aids or my younger son’s linear algebra exam or my older son’s allergies or calling the super to fix the dripping sink. I let go of thinking about why the rain is so torrential this year or if the deer are eating the hydrangeas or what will happen in the next election. My heartbeat slows and I am fully present—which doesn’t assure that the work will be worthy, only that I am doing the work.

Writing is the medium through which I can allow my imagination to go wild, through which I’ve learned to trust my intuition, to work so hard at times that my eyes gloriously ache. It’s how I’ve faced down fears and the ugliest parts of myself and how I’ve discovered the most fearless and worthiest parts of myself. Exchanging work with other writers has been among the most intimate experiences of my life: receiving the great gift of someone else’s full attention on my work and their dedication to helping it become its best version of itself; being granted the great privilege of another entrusting me to do the same.

If I do not write, I am unwell: deprived of the very thing that gives me sustenance. The same is true for me with reading, which for me is part of writing. I can leave the house without water or an umbrella, but never without a book and a notebook. We all have the rivers through which we navigate our lives and literature is mine—an infinitely fascinating current of ideas and feelings and for me, a portal into the most elevated modes of living. When my days are over, I will feel content and very lucky if I can leave my sons well in mind and body and a handful of my books in those majestic waters.

So let me end our exchange by flipping the question: What has it meant to you to have writing as the organizing principle of your life?

AED: Lisa, I love what you say here, and I say ditto to all of it. Writing is my meditation, too. Everything that is of present concern recedes during the hours I am writing, and I am untethered from how I interact of the world and what it makes of me. I do take myself to the page, my experience and knowledge, but my identity becomes far more fluid as I enter the sphere of imagination.

My experience of him is how I feel about characters. They pass through me, but they are not me, and when I am giving them their due I am relieved of myself for those hours.

I don’t know if our characters express aspects of ourselves, but it doesn’t feel that way to me. It feels more like this: One day when I was still living on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, in an old apartment, I was walking across the living room when a whole other person passed right through me. It probably lasted a second, but in that time I received complete knowledge of who he was, images of his life, what he was like. He was, above all, not me, but another entity entirely, unique and on his own trajectory that happened to intersect with mine at that moment.

It’s a ghost story, take it or leave it; it happened. My experience of him is how I feel about characters. They pass through me, but they are not me, and when I am giving them their due I am relieved of myself for those hours.

When I was a child, writing was an escape, a place to go to get away from the chaos around me. I was a seeker, and since I couldn’t see my way to committing to the life of a religious, I chose the path of writing as a way to temper my personality, shave down my ego, and see the world more directly. Sometimes writing has been an addiction. Sometimes a therapist, a medicine, a bearing wall for mental health. I was once told your art problems are your life problems. That gave me a fresh perspective on my writing, and I found that issues I thought endemic to the work weren’t—they were me.

These days writing is peaceful. I approach the page as I approach the feral cats I feed twice a day, with an attitude of curiosity, benevolence, and a lack of agenda. That may sound contradictory to the work of writing a novel, but I mean something separate from the important role played by executive functions—organization and planning. In the early morning writing sessions I have learned to be open and present.

The page, my pal, is present too, formidable and surprising and equal—exactly my equal, on any day. We have a good relationship, and so far, I have always wanted to get together again.

*

Alice Elliott Dark is the author of the novels Fellowship Point and Think of England, and two collections of short stories, In The Gloaming and Naked to the Waist. She is an Associate Professor at Rutgers-Newark in the English department and the MFA program. You can learn more about Alice and her work at aliceelliottdark.com.

Lisa Gornick is the author of five novels, including most recently Ana Turns and The Peacock Feast. A graduate of the Yale clinical psychology program and the psychoanalytic training program at Columbia, where she is on the faculty, she was for many years a practicing psychotherapist and psychoanalyst. You can learn more about Lisa and her work at lisagornickauthor.com.

______________________________

Ana Turns by Lisa Gornick is available via Keylight Books.