Ling Ling Huang on the Similarities Between Classical Music and Fiction Writing

“Music and writing demand the same things: self-discipline, time, and patience.”

For most of my life, I’ve made a career out of telling stories without words. As a violinist, I practiced six to eight hours a day to hone my technical skills and to find my distinct interpretation for any given piece. But notes are ephemeral. That fleeting quality can make performances a shared and sacred experience for those participating and attending, but I needed to find a path of self-expression that didn’t always disappear.

Writing has all of the exploratory nature of playing music, but to see my experiences and feelings etched on paper or typed out became cathartic and necessary. A record of self I could return to when I became unmoored.

This coming year will be my 30th as a professional violinist and my first as a published author. The only disheartening thing about bringing a book into the world has been the assumption by music colleagues that I’ve quit music. For me, writing and playing music go hand in hand and I would not be able to do one without the other.

Writing began as an act of translation for me. In my sheet music, I would write descriptor words that helped me create a clearer narrative and more intense feeling as a performer. These words ballooned into short stories, and one day, a novel. My professor could hear the difference writing had on my playing and encouraged the rest of my studio colleagues to annotate their music in the same way.

When I went home from college one summer, I looked at some of the music I had played when I was 8 or 9, and I was surprised to find notes scribbled all over my sheet music. By virtue of being non-verbal, classical music doesn’t prescribe feelings. Everything I wrote when I was younger stemmed from a moment in music that I couldn’t understand. It has always been my way of examining feelings I couldn’t parse, an attempt to express the ineffable.

Eventually, I used it to better understand the complex emotions I felt in other realms: adolescence, loneliness, and queerness. Music became a safe space for me as an other language. It was a place to explore my feelings of otherness for being queer and Asian American.

I needed to find a path of self-expression that didn’t always disappear.

Ceding artistic control is inherent in the profession of a classical musician; we depend on an audience to be heard, much less interpreted. We are taught that there is no one or right interpretation for a piece, or even a moment. Otherwise, how could we stand to play the same pieces over and over again? Each performance builds on the others, accruing meaning and depth. It’s the antithesis of a snap judgment or a hot take.

My interpretation of a favorite passage of music changes from day to day, depending on who I am and who I’ve been. And while writing started as a way to pin down moments of music into understanding, I find music instead teaching me the importance of writing with a wideness that allows for many different readings.

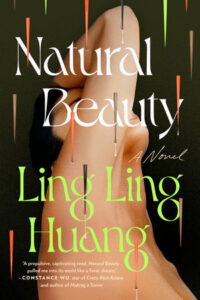

The two complicate each other: music teaches me the importance of writing ambiguity and writing shows me the possibility of specificity in music. Musical structures are the scaffold over which I build my stories. For example, my debut novel Natural Beauty, is set in the fascinating and unregulated world of clean beauty and wellness. I found the tone of the book by listening to Prokofiev’s Cinderella ballet which layers a beautiful fairy tale melody over a dark and ominous bass line.

When I’m stuck in one medium, switching to the other often loosens the tongue for both. The search for the best word in a sentence and the difference it can make has sharpened the meticulousness with which I make choices on my instrument about articulation, vibrato speed, and bow pressure. Writing reminds me that every creative endeavor is about play. Having no training as a writer, I have the freedom of being a beginner, of being allowed to fail in ways I wouldn’t allow myself as a violinist.

As grateful as I am for the many formal systems of education I’ve had, many of these institutions served to dampen my individual voice. Twelve years of rigorous music conservatory training sterilized me. Very few people find the line by which they can totally express themselves and still be gainfully employed. I learned how to express myself in ways that would be appropriate within an orchestra, because being in an orchestra requires you to sacrifice in order to adhere.

Music and writing demand the same things: self-discipline, time, and patience. When I sit down in front of the page or pick up my instrument, I must believe again and again that I can find something to offer a world that is already so full. For me, the act of creating is confrontational as much as it is confessional, and to confront the blank page is to believe in yourself as more than a creature of consumption.

There is a Zen Buddhist saying: how you do anything is how you do everything. I recognize in all of my pursuits the desperate need to confront and question the complexity of humanity, its many feelings and experiences. I consider it a great privilege to be a translator between music and words where the goal isn’t fluency, but connection between the two, and community with readers and listeners.

__________________________________

Natural Beauty by Ling Ling Huang is available from Dutton, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Ling Ling Huang

Ling Ling Huang is a writer and violinist. She plays with several ensembles, including the Oregon Symphony, Grand Teton Music Festival Orchestra, ProMusica Chamber Orchestra, and the Experiential Orchestra, with whom she won a Grammy Award in 2021. Her debut novel, Natural Beauty, was a Good Morning America Buzz Pick, a New York Times Editors’ Choice, and winner of the Lambda Literary Award for Bisexual Fiction.