Lincoln Michel on the Pulpy, Rollicking, Resonant Early Sci-Fi of John Wyndham

Way Back in 1936, Stowaway to Mars Asked: “Does man rule machine or do machines rule man?”

Before John Wyndham was John Wyndham—one of Britain’s finest science fiction authors of the twentieth century—he was other people. He was Johnson Harris. He was John Beynon. He was Wyndham Parkes and Lucas Parkes and more.

John Wyndham, whose full name was John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris, has a career that can be broken into two periods: the post–World War II “Wyndham era” and the prewar “pen name era.” After the war, which he served in, John Wyndham published novels under that name—such as The Midwich Cuckoos, Trouble with Lichen, and The Day of the Triffids—that helped define science fiction as a genre of serious and complex literature.

Before the war, Wyndham published work more in the vein of the pulpy adventures of the day that nevertheless show his penchant for unique concepts and genre subversions. The best of these early works is Stowaway to Mars. While not Wyndham’s greatest novel, the tale of tycoon spacefarers, a dying planet, and artificial intelligence resonates in strange and interesting ways with our current moment.

The year is 1981. An American millionaire has set off an international competition by offering a five million dollar prize—we can’t fault Wyndham for not accurately predicting inflation—to the first spaceship to reach another planet. In England, Dale Curtance unveils his ship Gloria Mundi and rushes to set off for Mars before any rivals can launch. Everything seems to be going smoothly until they leave orbit and discover the titular stowaway, Joan, who has a theory that what they’ll find on Mars is stranger than any of them is prepared for…

If my summary sounds pulpy, that’s intentional. First published in 1936—under the title Planet Plane and the name John Beynon—Stowaway to Mars appeared in the “pulp era” of science fiction. It was an age of color and camp. Spacefarers with chiseled jaws like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers filled newspaper comic pages and silver screens. Magazines like Wonder Stories and Weird Tales sat on newsstands displaying buxom babes and bug-eyed beasts.

This is the world that Wyndham first published in. His first science fiction story, “Worlds to Barter,” appeared in a 1931 issue of Amazing Stories under the pen name John Beynon Harris. This context is also important to understand the ways in which Wyndham, even in his early work like Stowaway to Mars, subverted expectations. First, it was rare for a space adventure story to contain prose like this:

Stars like diamonds, bright and undiffused, shone in brilliant myriads against a velvet blackness. Bright sparks which were great suns burnt lonely, with nothing to illuminate in a darkness they could not dissipate. In the empty depths of space there was no size, no scale, nothing to show that a million lightyears was not arm’s length, or arm’s length a million light-years. Microcosm was confused with macrocosm.

The plot also takes surprising turns. At first, Dale Curtance seems like your classic bold and handsome daredevil. The novel opens with Dale shooting a saboteur in his spaceship workshop. The reader might anticipate that he would take his new ship and sail to Mars to—like Edgar Rice Burroughs’s hero John Carter— battle evil Martians and mad scientists while winning the heart of a beautiful Martian princess. Instead, Dale is scuttled to the side and the stowaway, Joan, becomes the story’s center.

Once found, Joan explains how her father had discovered a bizarre machine that seemed to move with its own intelligence. No one had believed him. But Joan is convinced the machine came from Mars. While the men mock her, Joan’s theories of “intelligent, self-contained machines” are proved correct when they land.

While not Wyndham’s greatest novel, the tale of tycoon spacefarers, a dying planet, and artificial intelligence resonates in strange and interesting ways with our current moment.That is not to say the novel is not without more than its fair share of sexism. It is very much a novel of its time, to put it lightly. When Joan is first discovered, the crew members are only stopped from jettisoning her into space because she’s a woman. In the most cringe-inducing chapter, the male crew debates women’s natural fear of machines (because the “highest duty of woman is motherhood” and machines are rival creations… or some such nonsense).

And yet it seems possible to read Wyndham as attempting to subvert the attitudes of 1930s Britain. The buffoonish sexism of the shipmates invites our ridicule—“Speaking as a woman, what did you think of that mouthful?” Joan is asked after a round of mansplaining. “Not much,” she replies with a smile—and certainly the post–World War II Wyndham was capable of writing novels that feel downright feminist, most notably Trouble with Lichen. Still, even if Wyndham is subtly mocking the sexism of the age, that doesn’t save the narrative from repetitive chauvinistic comments and, even worse, two rape attempts (thankfully skipped past quickly).

Like most pulp era work, the reader must enter Stowaway to Mars without any concern for the “hardness” of the science fiction. This is a story where scientists happily taste water on a foreign planet and aliens somehow evolved to look basically human. But Wyndham did get some things right. In a cosmic coincidence, the novel posits a first trip around the moon in 1969, the same year of NASA’s real-life moon landing. The novel also rightly anticipates that space would be a zone of the Cold War. When Gloria Mundi lands on Mars, it is followed closely by the Soviet ship Tovaritch. And Dale’s private-enterprise Mars mission certainly recalls our own age in which wealthy tycoons like Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Richard Branson race one another to space.

The most interesting resonances with our age lie with the book’s central theme: What is humanity in the age of machines? Do we rule our inventions? Or is Dale’s wife, Mary, right to think that “the machines were the hateful dictators of men and women alike”? Wyndham didn’t predict an age in which political systems are undermined by algorithms, lives are increasingly entangled with social media, and automation threatens mass unemployment, but the questions the book explores about man’s nature to machines feels relevant. At one point, Dale says of machines, “a pianist losing his fingers would lose no more than I should if I were deprived of them.” The same could be said for anyone of us and our cellphones today.

The thematic questions are explored in the novel’s jampacked and rushed final third. (Perhaps here a spoiler warning is in order.) When the Gloria Mundi lands on Mars, Joan is shortly separated from the group. The men are left to squabble with the Soviets over whose empire should get to claim the planet they haven’t even yet explored. While this farcical subplot unfolds— one could imagine Armando Iannucci penning an adaptation—Joan finds herself touring the remains of the red planet’s civilization with the Martian Vaygan. Their calm, philosophical conversations about man versus machine, climate change, and the collapse of civilization contrast with the cartoonish action of the Dale plot.

Does man rule machine or do machines rule man? These are the thesis and anti-thesis positions of the novel. The Martians have found a synthesis. While humanity debates ruling or being ruled by machines, the Martians have calmly accepted replacement. Faced with a dying planet, the Martians don’t opt to adapt or colonize other planets. They barely even bother to procreate, for “each generation only prolongs our decay.

We have had a glorious past—but a glorious past is bitterness for a child with a hopeless future.” The Martians’ stoic acceptance also seems to provide a foil to the Great Man bravado of the novel’s supposed hero, Dale, who races to Mars for personal glory and immediately claims the planet and all its inhabitants for the British Empire without ever even seeing a living Martian.

Frustratingly, the last third doesn’t provide enough pages for Wyndham to fully explore the concept. (He never finished the sequel that is teased on the final page, although a follow-up story concerning the stranded Russians was published as “Sleepers of Mars” in 1939.) Reading Stowaway, one can’t help but imagine the Wyndham of the 1950s and ’60s spinning the idea into a science fiction classic. Instead, we are left with a rollicking, uneven though still thought-provoking adventure story. When you finish it and return to your cellphones and laptops while around you the planet burns, maybe you will wonder if one day in the future the remaining humans in a climate-ravaged world will say that the Earth has grown old and what’s left “is for the machines to decide, it is their world now.”

________________________________

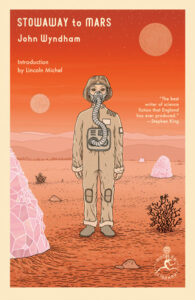

Introduction by Lincoln Michel to the book STOWAWAY TO MARS by John Wyndham. Copyright 1935, 1963 by the Executors of John Beynon Harris. Introduction copyright © 2022 by Lincoln Michel. Published by The Modern Library, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.