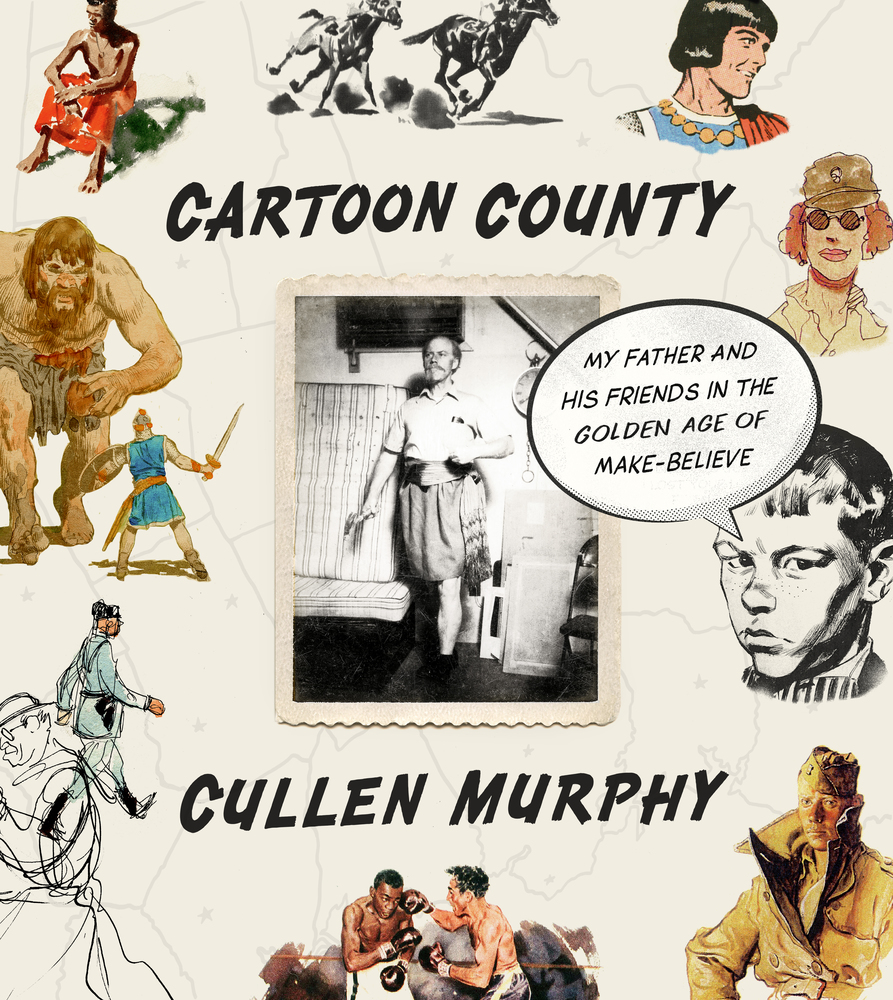

Life with a Legendary (and Eccentric) Cartoonist

On John Cullen Murphy, Master of the Comic Strip, Model to Norman Rockwell

Children arrive in a world already made. Their slates are blank, but all the slates around have long been written on. It was simply a given that both of my parents were selfless and energetic. That they could laugh at themselves and crack a joke. That they were politically conservative and believed in God. That my mother was outgoing, disciplined, and persuasive. That my father was a soft touch, and patient beyond reason. That his mind was an overstuffed attic whose door was ajar. That he could draw and paint. That even simple directions on a scrap of paper would be embellished with drawings of houses and trees, cars and cows.

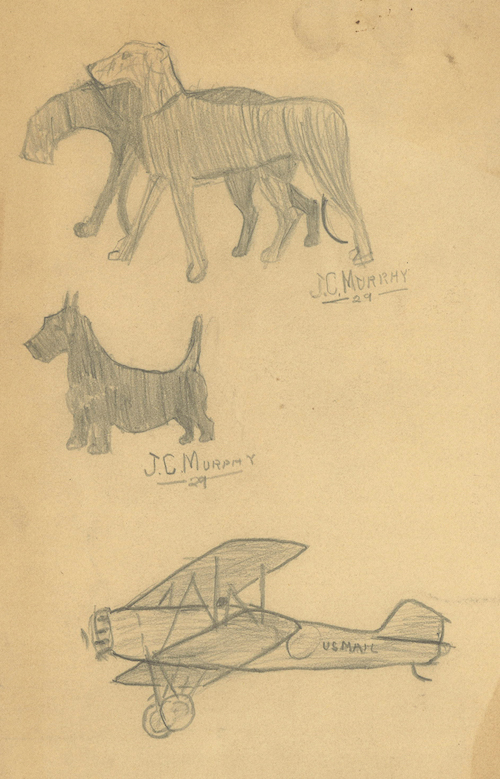

My father grew up in Chicago but was born in New York City. As if called by instinct to some distant spawning ground, his mother insisted on boarding the 20th-Century Limited and returning to her native Manhattan whenever the time drew near for the birth of a child. He began drawing at a very early age—and also began carefully saving his work, as if for posterity, starting when he was about five. Given posterity’s likely interest, he also began saving his tests and papers from school. My father signed his work carefully, first as “Jack,” the name he was always known by, and sometimes as “J.C.,” and only much later with the full “John Cullen Murphy.” An artist of some kind is all he ever wanted to be if he couldn’t be a baseball player, which he accepted early on he could never become. Once, late in his life, when asked by a fan to answer 20 questions about himself, he filled in the blank after a question about what had inspired him to do what he did with the simple response “Liking it.” His family had an independent streak and a taste for the mildly unconventional, and encouraged him in his ambitions. His own father had been by turns a book publisher, a book salesman, and a literary agent whose most prominent client was the novelist and poet Christopher Morley. His mother’s family included artisans and craftsmen of various kinds. One of them was a coppersmith who produced elegant housewares and small sculptures in the mission style. My father enrolled in drawing classes at the Art Institute of Chicago when he was seven. A few years later, after the family moved back east, he attended the Phoenix Art Institute and the Art Students League, in New York.

Drawings by John Cullen Murphy at age six.

Drawings by John Cullen Murphy at age six.

One unexpected stroke of luck was that his neighbor in New Rochelle was Norman Rockwell, whose studio on Lord Kitchener Road was about a hundred feet from my father’s back door. Rockwell had seen my father, then 14, with his unruly and very red hair, playing baseball at a field nearby—he looked like what we have come to think of as a Norman Rockwell character. Rockwell stopped by my father’s house one afternoon to ask his mother if young Jack could pose for some illustrations. In the ensuing years my father found himself appearing in Rockwell paintings. At age 15 he posed as David Copperfield for Rockwell’s mural The Land of Enchantment, which is in the New Rochelle Public Library. As a cross-legged teenager he was on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in September 1934, gazing at photographs of glamorous female movie stars. Starstruck is the title of the painting. A baseball glove sits by my father’s side, and a dog nuzzles at his knee. Rockwell once explained that, to make a posing dog or cat behave, you need only “apply a slight degree of pressure to the base of the cranium where it joins the spine.” In this instance, my father remembered, Rockwell also needed to add a sedative to the dog’s water.

Rockwell was an important figure in my father’s life. He would assign my father short stories to illustrate, then critique the work and send him back to try again. He also taught him how to paint in oils. The sketch of Rockwell’s that I have was for an oil painting by my father of Hemingway’s story “The Killers.” Eventually Rockwell arranged a scholarship for my father at the Art Students League, where one of his teachers was Franklin Booth, whose meticulous pen-and-ink magazine drawings were a mainstay of Harper’s and Scribner’s. Another teacher, even more influential, was George Bridgman, who had been Rockwell’s anatomy instructor and ran a life-drawing class that Rockwell insisted my father attend. Bridgman had studied with Jean-Léon Gérôme in Paris in the 1880s. Gérôme had been trained by Paul Delaroche, who had been trained by Antoine-Jean Baron Gros, who had been trained by Jacques-Louis David, who had been trained by François Boucher, who had been trained by François Le Moyne—if you had time, my father could likely have pushed the laying on of hands back even further, through Raphael and Fra Angelico to some muralist at Pompeii. This sort of classical training was standard at the time—the cartoonist Chon Day had studied with Bridgman, as had Stan Drake, Bob Lubbers, Will Eisner, and a host of other cartoonists. So had Mark Rothko. The anatomical studies that resulted, done in chalk or charcoal, resembled exercises that might as easily have been done in 1550 or 1870 as in 1936. Bridgman entered the class promptly with an aroma of cigars, alcohol, and authority. When one student, who later became the director of the Whitney, resisted Bridgman’s criticism of his work, saying, “I don’t see it that way,” Bridgman replied, “Consult an oculist.” I was always struck by how many cartoonists had built their careers on a traditional foundation, and how easily some of them could shift from comic mode to a quick pencil rendering of a nude or a tree that would have seemed at home in the Frick.

Drawings by John Cullen Murphy, age seven.

Drawings by John Cullen Murphy, age seven.

By the age of 17 my father had sold his first painting—of a horse race—to the Manhattan restaurateur Toots Shor and was drawing program covers for sporting events at Madison Square Garden, mainly boxing matches. In high school, he also developed his talent as a caricaturist; historically, high school has been an environment where that skill is in high demand. Within a couple more years, right around the time a much older Hal Foster was giving up Tarzan and launching Prince Valiant, my father had developed the style that would lead to covers for Sport, Liberty, Collier’s, Holiday, and other magazines. Becoming a cartoonist was not my father’s original ambition—it was an opportunity that came his way by chance after the war. He was intent on a career as an illustrator of magazines and books. And he remained an illustrator all his life, both in the kind of comic strips he drew and in the vast number of sketches and paintings he produced privately. In this he was like many other cartoonists. Most of them cultivated some complementary side of themselves that was more than a hobby and had nothing to do with what they were primarily known for. Jerry Dumas was an essayist whose spare, elegant drawings appeared in The New Yorker. Dik Browne created pen-and-ink landscapes and fantastical scenes that might have been etchings made by an impish Rembrandt. Rube Goldberg was a sculptor. Noel Sickles moved on from Scorchy Smith to magazine illustration—his drawings accompanied the first publication of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. Fred Lasswell, who wrote and drew Barney Google and Snuffy Smith, was an inventor— he came up with a method of producing comic strips in Braille and held a patent on a citrus-fruit harvester. Mell Lazarus, the creator of Miss Peach and Momma, was a novelist. Bill Brown, who wrote the comic strip Boomer, which was drawn by Mel Casson, had a sideline career on Broadway: he wrote The Wiz.

Stan Drake, whose parents had been close to Art Carney, tried his hand at acting. Carney told him it was no kind of life, but the actor in Drake came out when he posed himself for pictures. Jerry Marcus, who drew gag cartoons for many magazines and also created the comic strip Trudy, dabbled as an actor in movies and commercials for most of his life. If you watch Exodus, you can see him for an instant in the role of a British soldier crossing a street in the far distance behind Eva Marie Saint. When Marcus ran into her years later, on the set of another movie where he had another bit part, he asked her if she remembered him. She said no. He said, “We were in Exodus together.”

My father’s fluidity with a pencil is one of my earliest memories of him, and a reliable and familiar constant ever after. There was a practiced thoughtlessness and an easy physicality to it that you also see in chefs and carpenters, barbers and tailors. He never sharpened a pencil mechanically. The tip was trimmed with a single-edged razor, the wood shaved off in thin wedges as the pencil turned in his fingers after each slice. When a half-inch shaft of graphite core had been exposed he then abraded the surface on a piece of fine sandpaper taped to the desk until the tip was properly sculpted. The effect he sought was not a symmetrically rounded cone, as a sharpener would produce, but something more like a scalpel, the graphite coming to a point, but with sides that were long and flattened. My brothers and sisters and I sharpen pencils like this even now. As the pencil approached paper you could start to see his mind at work and the influence of Bridgman and his techniques, which were fundamentally architectural. He often began in an unexpected place—a nostril, a doorway—as if to put a stake in the ground. He then moved ahead lightly and loosely, the lines laid down in a way that at first seemed haphazard and chaotic until a sense of composition began to be discernible, like formless clouds gradually collecting into an image. He never used an eraser at this stage, but simply penciled over lighter lines with slightly darker ones as he grew more confident about what he wanted. His tendency was to move from the more general to the more particular, an approach that not only made sense when drawing but also reflected the conceptual hierarchy his mind applied to everything. He warned against getting too detailed too quickly—his favorite example was Michelangelo’s heartrending final Pietà, the one in Florence that the sculptor tried to destroy, with its polished arm and leg, expertly carved but hopelessly skewed in their overall proportions. The whole composition had been doomed from the start. “The masses of the head, chest, and pelvis are unchanging,” Bridgman had instructed. “Whatever their surface form or markings, they are as masses to be conceived as blocks.” Only when the basic structure was clear, and the blocks were in place, would my father move to the next level of concreteness, laying in the major shadows with the side of the pencil and then using the point to start the close work on prominent darker and sharper features—eyes, ears, hands, hooves, windows, branches. Time-lapse photography has captured the rapid, elegant arcs of a conductor’s baton; I wish my father’s graceful movements had been preserved the same way. His hand moved continually—settling in for a moment in one place, going back for a few strokes to another, coming again to where he’d just been—but there was nothing fussy or tentative about the motion. There was a sensation of inevitability: the picture starting to emerge had had no choice.

That was an illusion. For any cartoonist, the task of distilling some sort of invented reality into a series of blank spaces—one space for a singlepanel cartoon, maybe three for a black-and-white daily strip, as many as nine for some of the color Sunday strips—took thought and preparation. For a humor strip or a gag cartoon, ideas were the engine, and the standard exchange rate was about one usable idea for every three or four you might come up with. Sometimes ideas struck suddenly—it often seemed that a cartoonist’s mind was trained to see all situations first as material and only second as lived experience. “I can use that!” is the phrase you’d hear. One day, Mort Walker was at the grocery store, lost track of his wife, saw a stock clerk shelving cans, and heard himself asking, “What aisle are wives in?” More often, ideas required “thinking,” which to an untrained eye could look like dozing in a rocking chair or hitting golf balls with a putter on the carpet.

Realistic story strips such as my father drew—or strips like Rip Kirby and Brenda Starr—needed something different. They started with scripts plotted out months in advance, and involved an ever-changing variety of new characters and new locales. Preparation meant research and the snapping of all those pictures. My father’s inventory of what he called “scrap” was organized alphabetically in a bank of filing cabinets. Once or twice a week he would sit with my mother in the evening, chatting amiably while riffling through a pile of newspapers and magazines, looking only at the photographs. When he came across an image that might someday be useful—a publicity still from Lawrence of Arabia, a family on muleback in the Grand Canyon, a fortification plan for the Tower of London, a prizefighter’s cauliflower ear, an adman mixing cocktails, a killer being led to the electric chair, a child weeping over a broken doll—he would tear it out with a sharp flexing of the wrist that was scissorlike in its accuracy. With a clean incision he moved vertically down the page to his target, then executed full removal with a series of swift right angles. He would file the pictures away according to a classification scheme that Linnaeus or Roget would never have proposed but could not have improved on. Ne’er-do-wells, General would be further broken down into subcategories like Swarthy, Femme Fatale, Irish, Armed, Seaborne, Cowardly. The category Combat was followed by thick folders labeled Swordplay, Arthurian, Jousts, Duels, WWII, Gladiators, Metaphorical. There was a vast section on crime, another on sports, yet another just on horses (Racing, Rearing, Grazing, Frightened, Furious). Romance was another big one: Young Love, Unrequited, Dancing, Spats, Matchmaking, Heartbreak. The fattest file of all was simply labeled Faces—a grab bag of people who might visually inspire a character: Auden, Arendt, Dirksen, Hepburn, Goldwater, Wharton, Acheson, Bacall, Keynes, Woolf. The scrap filled 24 file drawers.

This was the full extent of my father’s organizational prowess. Like most other cartoonists he was a virtuoso at the drawing board, but his powers diminished with the square of the distance from its surface. There were some notable exceptions, Mort Walker being one, but cartoonists by and large were not shrewd businessmen, and their managerial sensibilities were frozen in a premodern condition. Their reverence for masking tape, which they would have considered to be a sixth basic element had they been ancient Greeks, was symptomatic: it was the stopgap remedy of choice, suitable for all basic domestic repairs and most bodily injuries. That our own household functioned at all was due entirely to my mother, Joan. If my father was the Prince Consort, devoted to his curious projects, my mother was Queen, Prime Minister, Lord Chief Justice, and Chancellor of the Exchequer rolled into one. Both of them in their different ways were intensely involved in the raising of eight children, somehow making each one feel like the center of attention. In the early-morning hours of Christmas, presents would be shifted suddenly from one pile to another to correct a numerical or volumetric inequality. But it was mainly my mother who dealt with the child-rearing logistics. She kept our mansard-roofed Victorian from falling apart too quickly, controlled the checkbook, bought the cars, managed the calendar, and posed stylishly in front of the Polaroid whenever the casting call came from the studio. She also served as the back-office vizier when it came to renewing or renegotiating the contracts that governed my father’s work. When he returned from round one of any such meeting, there would be a quiet marital conference behind closed doors, punctuated by my mother’s audible sighs and the occasional “Oh, Jack.” Then she would devise a battle plan for round two.

That an American comic strip industry could exist at all was due to an unseen army of women who played the role of irrepressible Blondies coping with the mayhem caused by all those clueless Dagwoods and their bright ideas. My mother had come from a large family known for its stamina and strength of will. Her own mother was decisive and imperious; she needed canes because of crippling arthritis, and leveraged them to effect when it came to parking spaces, tables at restaurants, and special favors from total strangers. She once was waved through to the gangplank at the Cunard pier in Manhattan by thrusting a metal forearm crutch through the car window and saying, “Officer, I have canes.” At home she used a crystal bell to summon help. It became a tradition to give her bells as gifts, making the wider family unwittingly complicit in its own servitude. My mother’s father, the son of an Irish maid in New York, had lost both of his parents by the time he emerged from his teens. Tutoring himself in trigonometry and other skills—I have copies of his meticulous notebooks—he became an aviator with the army during the Pancho Villa campaign, in 1916, then built a global career in maritime insurance. In a basement workshop his tools hung obediently inside crime scene outlines of each shape that he had drawn on the wall. Nails and screws were carefully organized, the twenty or so jars neatly labeled and lined up in a row. This was the stock my mother came from. Her organizational capacities were prodigious, sometimes outstripping what lesser figures might regard as prudence.

Having to send all those children off to school with homemade lunches was the kind of challenge my mother was born to solve. One September morning, before the start of the school year, a Bendix freezer the size of a sarcophagus was delivered to our home and installed in the basement. Later that day, my mother returned from the supermarket with a hundred or so loaves of Wonder Bread; large plastic pails filled with peanut butter, jelly, and mayonnaise; a hamper of egg salad; a butt of tuna fish; a hod of American cheese; and several yard-long tubes of sliced bologna. The age of artisanal sandwich-making was over. The era of efficient mass production had arrived. The family spent the day making the sandwiches we would consume for the entire year. As the hours went by, quality began to suffer. Episodes of industrial sabotage—peanut butter with bologna, tuna fish with jelly— afforded moments of amusement in the kitchen that would yield to horror in the classroom at a later date. The sandwiches were hauled down in bulk to the freezer, to be withdrawn as needed on school-day mornings. The Peasants’ Revolt came around February, when freezer burn set in.

__________________________________

From Cartoon County, by Cullen Murphy, courtesy Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Copyright 2017, Cullen Murphy. Featured image, self-portrait by John Cullen Murphy.

Cullen Murphy

Cullen Murphy is an editor at large at The Atlantic, where he was the longtime managing editor, and has also been the editor at large at Vanity Fair. He is the author of Cartoon County: My Father and His Friends in the Golden Age of Make Believe (FSG, 2017) and the editor of Just Passing Through: A Seven-Decade Roman Holiday: The Diaries and Photographs of Milton Gendel, out now from FSG.