Life Imitates Art: On The Sorrows of Young Werther, Moral Panic and the Power of Books

Ed Simon Considers the Phenomenon of Killing Yourself (and Others) in the Name of Literature

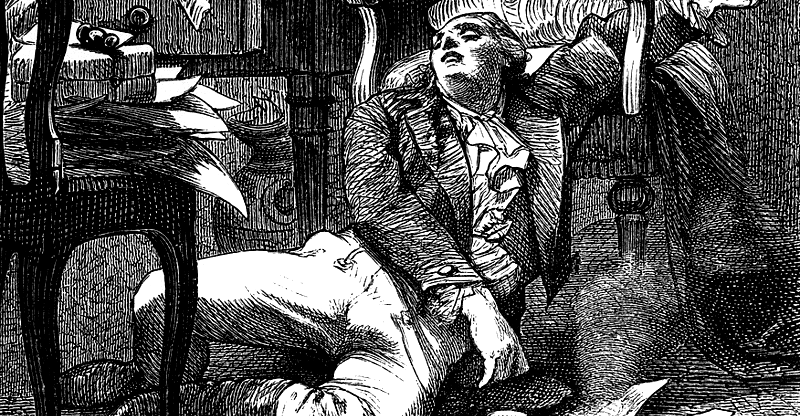

On a morning in 1807, a lovelorn, twenty-year-old German immigrant named Bertell settled on the sandy banks of the New Jersey-side of the Hudson River in Secaucus and carefully laid out a copy of his fellow countrymen Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (published more than three decades before) to page 70, where an underlined passage read, “They are loaded—the clock strikes twelve—I go,” placed a pistol to his head, and pulled the trigger.

Bertell’s discoverers described him as “genteelly dressed,” perhaps in the fashionable boots, blue jacket, and yellow britches and waistcoat of his favorite book’s titular character. At least that’s how many victims of the “Werther Effect,” copycat suicides in the fashion of Goethe’s protagonist, were reported to have outfitted themselves. In Germany and England, France and America, there were a rash of suicides like Bertell’s: men who were scarcely out of adolescence inspired by the self-destruction of Goethe’s Romantic hero.

The Sorrows of Young Werther propelled Goethe—only 25 when it was published 250 years ago—into literary superstardom. “Werther Fever” enveloped Europe, from Napoleon Bonaparte carrying a copy on his Egyptian campaign to a perfume marketed under the name. Goethe’s roman a clef details the sorry ending of its poetic-minded protagonist, rejected by both the nobility for whom he is too middling and the unconsummated love of a woman betrothed to another man. “The human race is but a monotonous affair,” writes Goethe, “Most of them labor the greater part of their time for mere subsistence.”

Fear about The Sorrows of Young Werther wasn’t necessarily that it would give you the wrong ideas about religion or state…but rather that it could infect you.

The novel is the primogeniture of Romanticism because The Sorrows of Young Werther exemplifies many of the attributes that we associate with Romanticism—the melancholy, passion, irrationalism—as well as the faith that life itself can be, must be, lived as if it were art. Ended as such too, for in the suicides that resulted there was the dark intimation that literature, more than mere pilfering diversion, was itself dangerous, had power.

Banned in Italy and Denmark, with the German city of Leipzig regulating Werther’s sartorial uniform for good measure, Goethe’s masterpiece was still hardly the first example of literature being accused of a pernicious influence. Socrates had castigated writing by claiming that it corroded humanity’s propensity for memory (though the sage was himself executed for corrupting the youth of Athens). His student Plato infamously banned poets from his idealized Republic, where they will not allow the “honeyed muse to enter, either in epic or lyric verse.” By the first-century, the lusty, sensual, and erotic Roman poet Ovid would be exiled by the moralizing Emperor Augustus to the Black Sea, punishment for “a poem and a mistake,” though the conjunction there complicates the charge.

Yet the language used to denounce Goethe’s novel didn’t concern treason or heresy, but rather contagion. Fear about The Sorrows of Young Werther wasn’t necessarily that it would give you the wrong ideas about religion or state (though perhaps that was implicit), but rather that it could infect you, that its influence was as epidemiological as it was intellectual. The first genuine literary moral panic.

We have not been for want of them since, even while death metal to Dungeons and Dragons, rap and Mortal Kombat, have long replaced fussy Goethe as the locus du jour. The long afterlife of the Werther Effect still animates how we think about literature, even as “comics and cartoons, popular theatre, cinema, rock music, video nasties, computer games, [and] internet porn,” as Stanley Cohen enumerates in Folk Devils and Moral Panics, have superseded Werther. Cohen writes that there is a “long history of moral panics about the alleged harmful effects of exposure to popular media and cultural forms,” even while he emphasizes that the “continued fuzziness of the evidence of such links is overcompensated by confident appeals.”

Such confident appeals include Senator Robert Hendrickson’s amazingly named Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency heard testimony in 1953 which hypothesized a lurid cover on Crime Suspense Stories (in this case featuring a woman’s dismembered head) would encourage homicidal impulses; in the ‘80s, feminist attorney Catherine MacKinnon allied with the conservative Concerned Women for America to argue that pornography encourages rape; Tipper Gore and the Parents Music Resource Source opined in 1985 against Prince, Judas Priest, AC/DC, and Twisted Sister for their sexually degrading lyrics. And yet, to date, no empirical studies have been able to conclusively draw a connection between what media represents and what it might make its readers do.

There are, however, some disturbing anecdotal examples. During the late nineteenth-century, so-called “Penny Dreadful,” novels printed on cheap wood-pulp paper, were often used as evidence in murder trials. The Secret of Castle Coucy and Cockney Bob’s Big Bluff—cheap, poorly written, mass-manufactured pablum often trading in true crime—were blamed for Emily Coombes’ murder at the hands of her two prepubescent sons in London, 1895. Much as with The Sorrows of Young Werther, Penny Dreadfuls were similarly blamed for suicides, such as with a 12-year-old in Brighton in 1892 and a Warwickshire farm hand in 1894. The verdict released by the inquest jury assigned to that first case blamed the boy’s death on “trashy novels,” a rougher estimation than that afforded to Goethe. Even while traditional literature was eclipsed by film and comics, video games and recorded music, books still could apparently exert a magnetic and occult power in convincing their readers to do the unspeakable.

“Art’s cruel,” says a character in English novelist John Fowles 1963 thriller The Collector, “You can get away with murder with words.” Many readers of The Collector, a harrowing story about a young art student kidnapped and sexually tortured by a stalker, have tried to get away with murder in reality as well. Copies of The Collector were found on the person of serial killers Robert Berdella Jr. in 1985 (guilty of six murders around Kansas City), Christopher Wilder in 1984 (with no less than eight murders throughout Australia), and Leonard Lake and Charles Ng who described Fowles’ novel as their “philosophy,” having named their operation after the imprisoned woman in the book (between them they raped, tortured, mutilated, and murdered twenty-five women and men in California).

Brett Easton Ellis’ notorious 1991 splatter-punk cult classic American Psycho, with its tale of financier Patrick Bateman killing people as easily as he finagles mergers and acquisitions, is rightly interpreted as a parody of ‘80s free-market excess. Sickening in its vivid descriptions of vivisection, Ellis’ novel was also found on the shelves of Australian mass murder Wade Frankum and Canadian serial killer Paul Bernardo. “My pain is constant and sharp and I do not hope for a better world for anyone,” says Bateman, “In fact, I want my pain to be inflicted on others,” and it would seem that in American Psycho some readers heard a voice that resonated.

Authors have occasionally advocated for the removal of their work, not unsurprisingly horrified to discover that a novel of theirs happened to be on the bedstand of a sadistic killer. Six school shootings took partial inspiration from Stephen King’s 1977 novel Rage, so that the author demanded his publisher take it out of print—they complied. Anthony Burgess appraised his A Clockwork Orange, an astute and disturbing examination of authoritarianism and thuggery, as “nauseating,” while Stanley Kubrick, director of the cinematic adaptation, lobbied to have the film removed from British theaters after a reports of copycat robberies, rapes, home-invasions, and murders.

Not that reason or sanity necessarily has much to do with a diseased consciousness’ justifications of atrocity, for after all it was J.D. Salinger’s poignant account of lost innocence in The Catcher in the Rye that somehow inspired Mark David Chapman to assassinate John Lennon outside of the Dakota on a cool New York afternoon in 1980. That was only twelve years after Lennon’s own lyrics on “The White Album” were “interpreted” by Charles Manson as instructions for murder.

To see books as incapable of danger is to understand them as being incapable of any power at all.

“You needn’t take it any further, sir,” pleads the murderer and rapist Alex in A Clockwork Orange, his eyelids strapped back as psychotherapists force him to watch horrific videos, “You’ve proved to me that all this ultraviolence and killing is wrong, wrong, and terribly wrong. I’ve learned me lesson, sir.” What inspired Alex to rape and kill in A Clockwork Orange—Beethoven, Wagner? Did Burgess’ novel influence adolescent Richard Palmer to murder a hobo in Bletchley, England in 1972, as The Daily Mail claimed? How about American Psycho, or Rage, or The Collector? Such questions are not least of all legal ones, but the issue is also literary, philosophical, even theological.

The censorious instinct claims that literature can be a malignant influence, while the humane and liberal spirit rejects that view, hewing to the reasonable position that “just books” aren’t responsible for any crime. In general, that’s the position that I’m inclined to agree with, but then I remember how many deaths the Bible has been responsible for.

It’s more than abundantly fair when examining the books read by a killer not to necessarily make a causal connection; presumably all those serial killers with copies of The Collector or American Psycho would still have been serial killers even had they not had library cards. Nickie D. Phillips in The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice writes that a “causal link between media exposure and violent criminal behavior has yet to be validated” while McKay Robert Stevens of Brigham Young University concludes that studies have “failed to find a significant impact of reading violent literature on aggressive cognitions.”

Yet if you were in Burgess’ or Fowels’ or King’s position, knowing that lives had been shortened purportedly because of sentences you wrote, that humans had been obliterated by cruel methods due to stories you had spun, how consoled would you be by The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice? The fact is that we expect, desire, and claim that literature is capable of changing lives—which I believe to be true. Why would that only ever be the case when it comes to changing lives for the better?

Cultural politics is normally engaged in an arena of Manichean posturing and bad faith. When it comes to the conundrum of if ugly words can be translated into uglier actions, the conservative is normally more than happy to break out the censor’s black marker, while the liberal historically defends even offensive media as “just video games,” “just music,” “just books.” I adhere firmly to the belief in free speech, not because language is never dangerous, but because it is a human’s inviolate right. But to say that books shouldn’t be banned because they’re “just books” seems to me to delegitimize the very idea of literature.

We wish for books to be the axe for the frozen sea inside us, the device that takes the tops of our heads off. We turn to literature for transmigration, transubstantiation, transformation. To see books as incapable of danger is to understand them as being incapable of any power at all, and that is a conclusion to which I cannot abide. Goethe, despairing at the thought of those who killed themselves, wrote that such unfortunates “thought that they must transform poetry into reality.”

The poet shouldn’t have been surprised, for the suicide of Karl Wilhelm Jerusalem who provided the model for Werther is instructive. On the bedside table of the dead man was a copy of Gotthold Lessing’s tragedy Emilia Gallotti, with its evocation of lives “tormented by unfulfilled passions.” Like so many of Werther’s acolytes, Jerusalem took leave of this life by falling into a book.

Ed Simon

Ed Simon is the Public Humanities Special Faculty in the English Department of Carnegie Mellon University, a staff writer for Lit Hub, and the editor of Belt Magazine. His most recent book is Devil's Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain, the first comprehensive, popular account of that subject.