Life By the Bay: A Moveable Feast That Moved When I Wasn’t Looking

Grant Faulkner on the Pressures of Living in San Francisco

To live in the Bay Area is to wonder whether or not to leave.

That was going to be my first sentence of my story. Then I was going to tell you about the nearly thirty-year conversation I’ve had with my wife, the writer Heather Mackey, about whether we should move to a place more hospitable to a couple of writing-addicted people, a place where you don’t have to duct tape your finances together to live, a place that’s perhaps more pastoral and certainly less pressured. It’s a conversation that has traipsed through a myriad of options of where we might go. There are the cities where creatives tend to gather, like Portland (97.5 percent of people in the Bay Area have at one time searched for homes in Portland on Zillow). There was a weekend trip to check out San Luis Obispo (once voted “Best Unheard-of Haven for Disaffected Broke People from the Bay Area,” or something like that). We once considered Ashland, Oregon (Heather almost got a job with the Shakespeare Festival!), and then I propose Iowa City at least weekly (I’m from Iowa, where life is full of simple pleasures and simple parking).

And then, in moments of especially piqued frustration—moments when the crampedness of our house is cramping us even more than usual or when we’ve run aground the shoals of our bank accounts—I make the joke (usually perceived as a taunt) that we should become creative writing professors at Mid-Central Arkansas State University. It’s a mythological place I dreamed up where we could drop out of our strident striving and teach aspiring writers at a comfortably mediocre college. We’d buy a house with a wraparound porch—cash down, thanks to our Bay Area real estate profits—drink endless gin and tonics, and slide into our elder years with a pleasantly debauched capaciousness of wallet, mind, and spirit. I have a friend who teaches in Arkansas, and I notice on Facebook how she has a much bigger house than we do and that she takes regular trips to Europe, which we don’t, so I’m sure she’s much happier than we are.

We’ve also considered Missoula, Montreal, Guanajuato, Berlin, and a very cheap stone house I found on the internet somewhere in Normandy.

But just after writing my first line for this story, serendipitously, or perhaps ominously, or perhaps damningly, a bookmark dropped out of the novel I was reading. Or rereading, rather—it was The Unbearable Lightness of Being, which I read for the first time soon after moving to San Francisco from Iowa in 1989. The bookmark was from Maelstrom Books, an old, creaky bookstore on Valencia near Sixteenth Street that I hadn’t thought of in years. It was one of several old Mission bookstores that have now passed from the memory of the city almost entirely. In fact, when I did a Google search for it, I could scarcely find a trace of it on the all-powerful World Wide Web (say what you will about them, but Silicon Valley tech bros know how to brand big stuff as big stuff).

I wanted to find a photo of it because I remembered it as a bookstore textured with mystery. Several fat, puffy cats always lolled comfortably about, giving the bookstore a cozy yet menacing air. Its stacks wended through the darkness, just one step away from messy (most of the used bookstores in San Francisco in this era were seemingly formed around messiness, defining intellectual pursuit not by a reading list charted on an app but by an endless, labyrinthine search through the yellowing pages of dog-eared texts). The black bookmark that fell out of my book and stared up at me had a Dadaist image of a man’s head with two swans wrapped around his neck that was collaged on top of someone else’s smaller running body (now that’s branding, World Wide Web folks!).

I picked up books published by presses I’d never heard of, books that felt alluring and dangerous, as if they’d prick me with new thoughts.

This bookmark derailed my intended initial sentence because it evoked a much more important story, one that’s more dramatic and surely more interesting. There’s sex involved, for one thing, and a concluding answer—finally, after all these years—to whether we are leaving the Bay Area. I’ll tell you that story now.

*

Bookstores like Maelstrom, and the literary scene that spawned them, were the reason I moved to San Francisco. When I first came to San Francisco as a young English major from Iowa during my spring break in 1987, I arrived with only one piece of advice: A friend told me that if I did just one thing in San Francisco, I had to go to City Lights, a bookstore and publishing house owned by the doyen of the Beats, Lawrence Ferlinghetti. I’d never be the same again, he said.

When I walked through the doorway, I was drawn in, seduced. I didn’t just see rows of bookshelves; I heard the exotic call of the ideas and stories that seemed as if they were part of the air itself. I walked from room to room, each one a mysterious cavern, a haven. I picked up books published by presses I’d never heard of, books that felt alluring and dangerous, as if they’d prick me with new thoughts. I bought as many as I could afford, and then went to Cafe Vesuvio, the bar across the alley from City Lights where the Beats themselves had thrashed through ideas over too many drinks, and I immersed myself in the lawless careening of their words, enthralled by an edgy, searching, incandescent expression I didn’t know was possible.

Thus began my love affair with the roguish spirit of the Bay Area and its literary tribes of misfits, dropouts, and seekers. San Francisco was a place where so many writers had lived out their insurrectionary impulses and beliefs—a place that had served so many authors as a place of refuge, escape, and even salvation from the rest of America. I have always loved it as a city sparked by the raucous boom-and-bust spirit of the gold rush, a place where people have always exuberantly and recklessly searched for different kinds of fortunes, a city that disregarded the need for stability, resting precariously on a restless fault line, inviting gate crashers who strove to push the limits of being and shake up all forms poetry and prosody.

“It’s an odd thing, but everyone who disappears is said to be seen in San Francisco,” said Oscar Wilde. It was a city for those who feel “other,” who feel lost, and then find themselves in a home they hadn’t known was theirs.

We were like a species of an animal that was so comfortable in our habitat that we didn’t quite realize we would soon be hunted to extinction.

My weekends in those days were spent getting lost—getting lost to find myself. I’d read and write for hours at the Café Macondo on Sixteenth Street, a living room (or a sanctuary, really) full of mismatched antique furniture, socialist poetry, and pictures of Che Guevara. After I’d finished my carrot cake and a third cup of coffee, I’d go across the street to Adobe Books, a bookstore dedicated to teetering stacks of books that looked like they’d been on someone’s list to be shelved for years. There was always a scrum of grizzled poets and communists huddled up front around the bookstore clerk, who was more interested in conversation than commerce, their teeth shellacked brown from coffee and cigarettes, the wisdom of labor strikes and ’60s protests furrowed in their brows. I’d buy a novel by Kathy Acker or a dusty edition of The Collected Works of C.G. Jung or a book of essays by Octavio Paz before moseying over to the famous Picaro café, where my friend Jake had scored a job and might sneak me a free latte. There, I’d sit and gaze at all the San Francisco characters chatting and reading and debating and playing the ukulele and falling in and out of love—and leading revolutions, of one kind or another, always.

Sometimes, a man known as the “Red Man” would come in. He colored his face and hands bright red, and he modeled a devilish Salvador Dalí mustache. He was always around the neighborhood, as if the city were paying him to be the Red Man, to prance up and down Sixteenth Street in a bustle of busyness and panache, a dandy often dressed in a 1970s tuxedo and immersed in a grand and dramatic project of utmost importance known only to himself. Meanwhile, a tall old hippie known as Lone Star Swan stood calmly at the corner, handing out his wordy and intricately illustrated photocopied newsletters, smoking a Tiparillo and gazing silently at the world from under his black headband as if he’d taken too much acid in the ’60s. And the ’70s. And the ’80s. The two were like a version of a flag waving over the Mission, a flag that represented revelry and madness, a flag that told us life held spectacular, colorful glories, even if they were doomed. And the Red Man was doomed, dying ten years later from the food coloring he used to paint himself red, which poisoned his blood and damaged his internal organs.

We were all doomed, really, doomed without knowing it. We were like a species of an animal that was so comfortable in our habitat that we didn’t quite realize we would soon be hunted to extinction. We drank at the 500 Club when it was an actual dive bar and not just marketed as a dive bar, blind to the tech companies moving in, not truly hearing their utopian promises and fanfare, not realizing that all the money flowing through them like a gushing river would also flow into snatching up Bay Area real estate and juicing San Francisco rents. We dined on heaping platters of Mexican food in the kaleidoscopic festival of bright holiday lights at La Rondalla. We went to poetry readings at the Elephant Café, where street poets like Julia Vinograd read during the weekly open mic and a gruff bartender with the thickest walrus mustache on the planet served the cheapest red wine on the planet.

We bought precious books by precious experimental authors at Small Press Traffic, a bookstore that only sold literature published by small presses (imagine that). We bought ravioli and salami at Lucca, an Italian grocer that had been there since the turn of the century, thumbed through magazines on UFOs at Naked Eye while picking out bootleg videos to watch, and then we’d go hear Angela Davis speak at Modern Times Bookstore, which not only carried tracts on Central American politics, but also books in Spanish.

The night was always young back then, and bars always awaited us. We might start the evening with a drink at Noc Noc, where broken old TVs with fuzzy reception ushered us into a cavernous space with warped walls that promised something in between a psychedelic nightmare and a utopian vision, and then we’d elbow our way into the sweaty, thrashing crowd that might be watching Pansy Division or Primus at the cramped Chameleon (later Amnesia) bar on Valencia Street. Cigarettes were a vital part of the world then, so “Peachy Puff” girls sashayed through the night as if walking straight out of a supper club in 1927, attired in retro cigarette girl costumes, carrying a tray of cigarettes and candy for extra nocturnal fuel.

Afterward, we’d traipse across the street to the Crystal Pistol, which showed old porn movies on TVs that hung over the bar as a marker of the club’s decadence. (San Francisco remained buoyantly and energetically sex positive, even as AIDS lurked throughout the city, seemingly colored in the erotic permission slips for safe sex that sex-positive feminists like Susie Bright and the nearby Good Vibrations handed out.) I remember having one (or thirteen) too many drinks and dancing with abandon to Deee-Lite’s “Groove Is in the Heart” under spinning disco lights long into the wee-est hours of the wee, wee night, and then ending up at Sparky’s, one of the city’s few all-night diners, for eggs and coffee.

The ineffable numen of a place can somehow define our essence. We’re told that we have five senses, but I think we have many more. There’s our sense of movement, our sense of time passing, our sense of the future, our sense of the past, our sense of others’ emotions, our sense of our dreams, and many others. All these senses combine into a sense of place, which has little to do with geography and everything to do with who we are.

Our sense of place is as important as the other senses because it provides the sense of belonging, and without knowing it, I belonged in San Francisco in the early ’90s, no matter that I wasn’t quite as hip as the other hipsters (I thought about but eventually balked at getting a tattoo of barbed wire around my bicep), no matter that my leftist politics placed me nearer Jerry Brown than Che Guevara. Whether I was doing yoga in the attic of an old Victorian on Dolores Street (yoga studios were still rare and exotic in the early ’90s) or going on my weekly pilgrimage to Fort Mason on the 49 bus to page through the slim binders of jobs at Media Alliance, desperately trying to find a job that better suited my college education than my gig as a waiter, or walking with hordes of people through Golden Gate Park for a free concert, I belonged to San Francisco, and my Midwestern self was fading away.

And yet, the place I belonged to was just about to depart. To be usurped, really. As the dot-coms rolled in, finally providing those jobs that were better suited to my college education, some of my poor writer friends became digital marketers and content providers and would soon climb the ladder to earn more money, and then more again, because it took more and more to live here. Others left for places like Portland, LA, and Austin, places they hoped would provide an easier and more creative life. The rest were pushed out. Rudely pushed out by escalating rents. We thought the Mission, the city, was ours, and didn’t understand how such a thing could be for sale. We were futurists looking in the wrong direction.

__________________________________

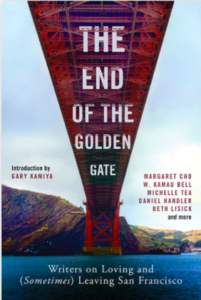

Excerpted from The End of the Golden Gate: Writers On Loving and (Sometimes) Leaving San Francisco, edited by Gary Kamiya. Copyright © 2021. Reprinted with permission of Chronicle Prism, an imprint of Chronicle Books.

Grant Faulkner

is the executive director of National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) and the cofounder of 100 Word Story. He has published two books on writing, Pep Talks for Writers: 52 Insights and Actions to Boost Your Creative Mojo and Brave the Page: A Young Writer’s Guide to Telling Epic Stories. His essays on creativity have been published in the New York Times, Poets & Writers, LitHub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer. He’s also cohost of the podcast Write-minded.