This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

There are two kinds of shy person. One kind—the writer—stands at a distance, observing everyone else in the room.

I’m the other kind of shy person, the kind who stands at a distance, examining a rock, and then jumps out of her skin when someone talks to her.

It’s not that I’m uninterested in people. It’s that to me, rocks are people, as are all inanimate things, and drawings, which are my specialty. And people are not. They’re too changeable, too erratic to ever see clearly enough. Besides, they can see you, too.

Even though I shouldn’t be a writer, I am a writer. It started when I was twelve. I was lonely. Rocks had suddenly stopped keeping me company. I was ready to give people a chance—I just didn’t know how to talk to anyone. Instead, I found books. I carried ten or twelve of them with me wherever I went, and read bits of them constantly. I wrote at night, in bed. I filled journals. Afterwards, I threw them out, to get rid of any trace of myself. Because I knew I was a little weird.

As inevitably happens, when I was fifteen, an odd boy I had an odd relationship with—the first of many odd boys I had odd relationships with—introduced me to Indie comics. At the time, comics didn’t feel like a different medium, just a different style of writing. Note that this was 2004: most books seemed to be by ill-adjusted, horny men. Comics were no different. This was fine by me (this was, as I said, 2004, and the way things were was the way things were). Which is to say that I knew about comics and liked them and even drew them but there was no “aha” moment. I chose a lane at the end of college (art school, actually), when I won a fellowship to make a graphic novel. I didn’t finish that project, but did finish and publish the next one.

Comics, like movies and plays, are a very dialogue-heavy form (thanks, the speech bubble). They’re great for human drama. My favorite comics are ones about couples, families, friends hanging out. I even love superhero comics, about good guys and their buddies interacting with bad guys and their henchmen (more boyfriend influence, yes). I can’t really imagine a comic that’s internal rather than centered on human interaction. I can’t imagine a movie or TV show like that, either. Being a comics artist with a limited understanding of human interaction is like being a pop singer with no interest in romance or a poet who’s not preoccupied by death. Tragic. Absurd. Inevitable. We’re drawn to what we don’t understand.

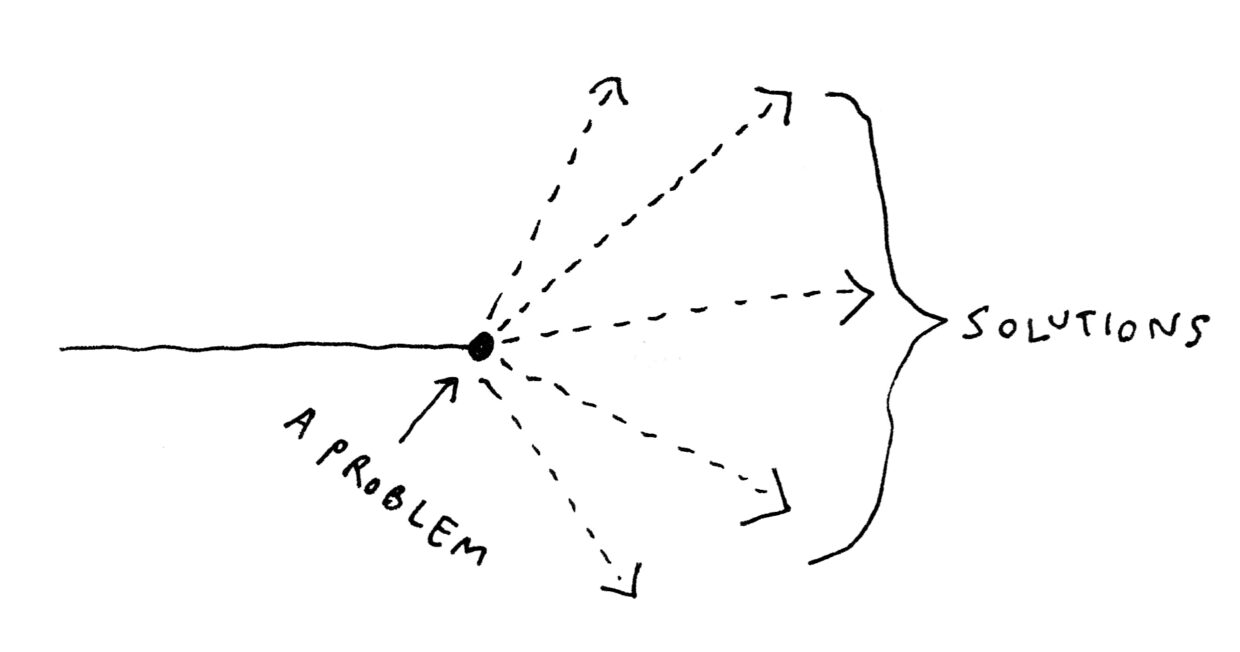

I️ won’t tell you how I️ handle this problem, because I think I handle it differently in every project. I will only say that it—the problem—has been a through-line in my work. I don’t think problems are bad, I should say. We don’t need to solve them. Just to confront them. Confronting problems is the great delight of making art. I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’ll never make the kind of comic book I love to read—a delicious drama. But it’s OK, because other people can do these things. And I do other things.

A problem can be framed just as easily as a strength: I have a gift for seeing the souls of non-human things. My books may not be about people, exactly. But they are people. And they are me.

__________________________________________________

How to Baby: A No-Advice-Given Guide to Motherhood, with Drawings by Liana Finck is available now via Dial Press.

Liana Finck

Liana Finck is the author of Passing for Human and a regular contributor to The New Yorker. She is a recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship, and a Six Points Fellowship for Emerging Jewish Artists. She has had artist residencies with MacDowell, Yaddo, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Center, Headlands Center for the Arts, and Willapa Bay.