Lev Grossman: Why We’ve Always Needed Fantastic Maps

From Narnia to Dungeons & Dragons, on the Allure of Imaginary Places

Until very recently there was a large foreign-language bookstore in Cambridge, Mass. called Schoenhof’s. Before it closed in 2017 it had been there for over 150 years. When I was in college—before I admitted to myself that I was basically cognitively incapable of learning any actual foreign language—I sometimes shopped there. I don’t remember much about which books I bought at Schoenhof’s, apart from a more or less obligatory undergraduate infatuation with the works of Gerard de Nerval (“Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la Tour abolie…”). But I do remember the bookmark they gave you when you bought something. It had the store logo in the foreground, and in the background, doodled there by some journeyman graphic designer, was a map, presumably intended to evoke the foreign-ness of Schoenhof’s books.

It wasn’t a map of anywhere in particular, and really it was just a fragment of a map, but I still remember some of its topographical details: smooth gray rolling hills, with a crooked little blue river wiggling its way down and out on to some nameless plains. I was weirdly fond of this mysterious cartoon land, and when I was out of sorts over something, a bad grade or some romantic reversal, which was pretty often, I would sometimes think about the Land Behind the Schoenhof’s Logo, and how when I eventually went to live there I wouldn’t have these kinds of problems anymore.

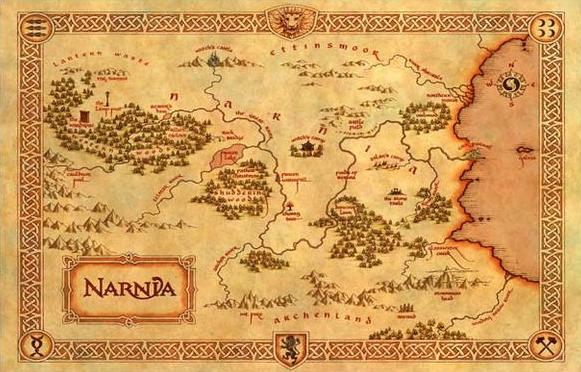

I mention this as one example of the strange narcotic power that maps have, especially fictional ones, even when they’re present only in trace quantities. Of course I also had the usual transports over maps of Middle-earth, and Narnia, and the archipelagos of Earthsea, and the Hundred Acre Wood, and The Lands Beyond, where The Phantom Tollbooth took place. But I could get a contact high just from the cartographical border of the Uncle Wiggily board game. All maps are fascinating, but there’s something extra-mesmerizing about maps of places that don’t exist. Maps are part of the apparatus of reality, and the navigation thereof. There’s a subversive, electric pleasure in seeing them miswired up to someplace fictional. In most cases, the closest you can get to actually visiting the land in a fictional map is by reading about it. But in my youth I got a little closer. I did this by playing Dungeons & Dragons.

Dungeons & Dragons isn’t so much a game as a kind of playable spoken-word epic. The Dungeonmaster tells the story, the audience controls the heroes’ actions, up to a point, and the role of fate is played by dice, some of which have more than the usual number of sides. The action takes place in imaginary landscapes, which are, of course, mapped. I don’t know what form they take now, but back in the day the maps of D&D and its heirs had a distinctive look. They were drawn on graph paper, with one square typically standing in for ten square feet of territory, with the result that the topographical features inevitably tended to take on a certain right-angled chunkiness. Because it was useful, in the interests of orderly gameplay, to keep the players confined in windowless interior spaces—it stopped them from wandering off and out of the storyline—the maps were often of underground caves, or the interiors of tombs, or the basements of castles. Caves of ice outnumbered sunny pleasure-domes.

The stories were usually pretty thin, concocted out of the bits and leavings of dozens of fantasy novels and mythological traditions, which were mixed and shaken together and served up like a cocktail. But those cocktails could be potent. For recovering addicts the names alone are enough to quicken the blood. The Keep on the Borderlands. White Plume Mountain. The Shrine of the Kuo-Toa. The Glacial Rift of the Frost Giant Jarl—”Jarl” being of course the frost giant’s title, not his name, a subtlety which eluded me as a child.

One’s eyes quickly learned to hungrily parse a newly acquired map: the long spindly corridors, the secret doors, the treacherous mazes, the crooked borders of unworked stone, the grand hall where the massive showdown melee would happen, the over-elaborate legend listing symbols for urns, statues, pillars, traps, treasure chests and altars to nameless gods. These maps promised extremes of excitement and pleasure, though players weren’t actually supposed to see the maps, strictly speaking. D&D wasn’t a board game: the map was a holy mystery, concealed during gameplay behind a makeshift cardboard screen. The Dungeonmaster would instead painstakingly describe a player’s slow, bloody progress across it. Denied the aerial omniscience of a map, one was in the position, increasingly inconceivable in the age of Google Maps, of being lost on a darkling plain, stumbling towards an unseen goal, with only words to steer by. All this only heightened the eroticism of the map itself.

“Denied the aerial omniscience of a map, one was in the position, increasingly inconceivable in the age of Google Maps, of being lost on a darkling plain, stumbling towards an unseen goal, with only words to steer by.”This eroticization could and did eventually lead to a depraved fetishization of the map over the actual game. As I got older we went from playing the game to just sitting around studying and discussing the maps, and eventually to drawing new ones ourselves. During the heyday of D&D, in the early 1980s, untold acres of graph paper and mountains of graphite were consumed in the making of millions of square miles of imaginary real estate—it may have been the greatest fictional land boom in history. Most of that land went unexplored. The thrill of contemplating it from afar outstripped the actual satisfaction of visiting it. The map had finally usurped the territory.

It was bound to happen. Travel is hard work, and as it turns out, even playing a game about traveling is hard work. It takes time. One of the feats that maps perform is to take all that arduous linear time and flatten it out into space. It’s a story, the story of a journey, but one that can be consumed like a picture, effortlessly and all at once. Anybody who’s ever traveled anywhere has had the experience of looking longingly at a spot on a map, then going to a lot of trouble to attain it, only to discover that it’s no less mundane than the place they started out at. A map is a promise that the territory doesn’t always keep, a paper currency that can’t always be redeemed.

*

When I was a kid, in the 1980s, fantasy was not entirely OK. It was fringey and subcultural and uncool. In my suburban Massachusetts junior high, to be a fantasy fan was not to be a good, contented hobbit, working his sunny garden and smoking his fragrant pipeweed. It was to be Gollum, slimy and gross and hidden away, riddling in the dark. Not that this stopped me, or a lot of other people. C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Ursula Le Guin, Anne McCaffrey, Piers Anthony, T.H. White, Fritz Leiber, Terry Brooks: I read them to pieces, alongside the all-consuming world of D&D. But I did these things privately. In the wider world, of which I was reluctantly a part, a love of fantasy was a sign of weakness.

But this has changed. Something odd happened to popular culture around the turn of the millennium: whereas the great franchises of the late 20th century had tended to be science fiction—Star Wars, Star Trek, The Matrix—somewhere around 2000 a shifting of the tectonic plates occurred. The great eye of Sauron swivelled, and we began to pay attention to other things. We paid attention to magic. In the late 1990s, Harry Potter started levitating up the bestseller lists, but Harry was only the most visible example. The first part of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy came out in 1995. Robert Jordan was writing the The Wheel of Time books. George R.R. Martin published A Game of Thrones in 1996. When I was a kid a big mainstream movie based on a fantasy novel was a deeply implausible proposition, but The Lord of the Rings arrived in 2001 and won four Oscars. Eragon, World of Warcraft, Twilight, Outlander, Percy Jackson, True Blood and the Game of Thrones TV show all came tumbling after.

And fantasy wasn’t just growing, it was evolving. People were doing weird, dark, complex, profane things with it. In 2001 Neil Gaiman published American Gods, an epic about seedy old-world deities trying to scratch out a living in secular strip-mall America. In Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell Susanna Clarke told the story of a rivalry between two wizards, in the Napoleonic Era. I got my hands on a copy of Jonathan Strange in May 2004, and by June I was writing a fantasy novel of my own.

Fantasy wasn’t a fringe phenomenon anymore. It had become one of the pillars of popular culture and, increasingly, the way we tell stories now. But why fantasy? And why now? It’s interesting to compare the present moment to another one when fantasy was a big deal: the 1950s, the decade when The Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings were published, two of the founding classics of modern fantasy. By that time in their lives, Lewis and Tolkien had lived through massive social and technological transformations. They had witnessed the birth of mechanized warfare—they were both survivors of the Great War. They had seen the rise of psychoanalysis and mass media. They watched as horses were replaced by cars, and gaslight by electric light. They were born under Queen Victoria, but the world they lived in as adults looked nothing like the one they’d grown up in. They were mourners for a lost world, alienated and disconnected from the present, and to express that mourning they created fantasy worlds, beautiful and green and magical and distant.

We’ve lived through some changes too, albeit of a somewhat different kind. If my generation is remembered for anything, it will be as the last one that can recall the world before the Internet. You can’t compare what we’ve gone through to the First World War, because that would be insane, but it’s not a trivial thing either. The changes we’ve witnessed have been largely invisible, but still radical: they happened in the sphere of information and communication and simulation and ubiquitous computation.

Which is why it makes sense that so much of the 20th century was preoccupied with science fiction, a genre that, among other things, grapples with the presence of technology in our lives, our minds and our bodies, and with how our tools change the world and how they change us. Those issues are of paramount, urgent importance right now. But a countervailing movement is happening too: we’re turning to fantasy. It’s counterintuitive, because fantasy is so often set in pre-industrial landscapes where technology is notable for its absence, but it must have something we need. We like to celebrate this world, our new world, as a paradise of connectedness, a networked utopia, but is it possible that on some level we feel as disconnected from it as Lewis and Tolkien did from theirs?

Look at your phone, the avatar of the new networked reality. It’s not miles away from the kind of magic item you’d find in Dungeons & Dragons: it shows us distant things, lets us hear distant voices, gives us directions, divines the weather. Our phones go everywhere with us, they present themselves as intimate friends—but they also have a cold, alienating quality to them. They connect us to other people, but they create distance too. Maybe they’re not giving us the kind of connections we need.

God knows, characters in fantasy worlds aren’t always happy: if anything, the ambient levels of misery in Westeros are probably significantly higher than those in the real world. But people in that world are not distracted. They’re not disconnected. In the real world we’re busy staring at our phones as global warming gradually renders the planet we’re ignoring uninhabitable. Fantasy holds out the possibility that there’s another way to live.

__________________________________

From The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, edited by Huw Lewis-Jones. Used with permission of The University of Chicago Press. Copyright © 2018 by Lev Grossman.