Dolores Dorantes and I became friends nine years ago, in LA. In those days she was staying in a trailer in a mutual friend’s backyard. She had just fled Ciudad Juárez, her home for 25 years, after receiving death threats, and she had seen enough friends killed to know the threats were real. Our mutual friend—Dolores’s longtime translator, Jen Hofer—asked if I wouldn’t mind giving Dolores the occasional ride. I didn’t mind. I had just returned from my first reporting trip to Palestine. Two years later I would move there. When I moved back to Los Angeles, late in the summer of 2014, the war winding down in Gaza, I ended up in that same trailer. Dolores, who was by then living in El Paso, was one of the few people I still knew how to talk to, and to whom I didn’t have to explain a thing.

Over email last month, we were planning to discuss the deserts we both love—respectively, the Mojave and the Chihuahuan—but we ended up writing about the war that is already underway, about race sickness, the shape of time, and the importance of never, ever obeying. I wrote to Dolores in English and she responded in Spanish and when we were done we translated each other.

–Ben Ehrenreich

*

Ben Ehrenreich: How is your desert over there?

[BE: ¿Cómo está tu desierto allá?]

Dolores Dorantes: Mi desierto está muy caliente. Tengo en la memoria la fotografía del presidente en un hospital de El Paso con el dedito gordo hacia arriba como signo de aprobación y Melania cargando un bebé completamente lánguido. Mostrándolo a los medios como el trofeo obtenido después de haber soltado a sus perros de cacería. Me sorprende la forma en que la memoria es capaz de guardar una imagen que representa el shock de una ciudad y, al mismo tiempo, es un shock en sí misma: shock sobre shock.

Desde entonces nada ha sido igual. El perfume de las lilas flota en abril y el agua se arrastra silenciosa bajo la superficie, pero no nos gusta la cacería. La temperatura excede 106. Las fronteras cerraron. Niños migrantes continúan muriendo en campos de concentración. Y comenzó a predominar el sonido puro de un desarrollo urbano multimillonario.

Los racistas clavaron una rodilla en nuestra garganta.

La tecnología bélica sobrevuela mi barrio y discretamente avanzan camionetas de la USIC. Esto está infectado, querido. Entonces decidí enamorarme. En el centro del territorio devastado encuentro los ojos del amor. Abrazo todo el miedo que siento. Me despierto a las 2 de la mañana con ganas de correr. Y recuerdo: un término despectivo para los negros: “prieto”. “Prieto” mientras veo mis tenis en la alfombra y amo esa palabra que me envuelve. Y regreso a dormir.

¿Y tú?

“Here you can feel the relief, like something ended and we survived, but it’s clear to me that nothing’s over yet.”[DD: My desert is very hot. I have a memory of that photograph of the president at a hospital in El Paso with his little fat finger up like a sign of approval and Melania holding a completely languid baby. Showing it to the media like a trophy picked up after letting the hunting dogs loose. It surprises me how memory can hold onto an image that represents the shock of a city and that at the same time is a shock in itself: shock on top of shock.

Since then nothing has been the same. The perfume of lilacs drifts in April and water crawls silent beneath the surface, but we don’t like hunting. The temperature is over 106. They closed the borders. Migrant children are still dying in concentration camps. And the pure sound of a multimillion-dollar urban development has begun to dominate.

The racists jammed a knee into our throat.

Military technology flies over my neighborhood and USIC [United States Intelligence Community] pickup trucks drive discretely by. This is infected, my dear. I decided to fall in love. In the center of this devastated terrain I encounter eyes of love. I embrace all the fear I feel. I wake up at two in the morning wanting to run. And I remember: a derogatory term for Black people: “prieto.” “Prieto” while I stare at my sneakers on the carpet and I love this word that envelopes me. And I go back to sleep.

And you?]

BE: I’m okay. I’m healthy and no one is trying to kill me and I haven’t lost anyone close to the virus. Being in Spain has been strange. Covid hit hard here and the lockdown was quite intense, stricter than in most parts of the world. But it worked. For now new infections are negligibly low, and the restrictions have been loosening up, so it’s as if the city is breathing again. There’s still not much traffic and in the evenings, when we’re allowed to go out for exercise, the streets and squares fill with people. No one’s in a hurry, they’re just happy to be outdoors, alive, together. It feels like a new way of living in a city.

But of course about 90 percent of my head is in the US, with cops in riot gear marching through and the virus still raging, so the disconnect can be extreme. Here you can feel the relief, like something ended and we survived, but it’s clear to me that nothing’s over yet, that whatever is happening has only just begun.

[BE: Estoy bien. Nadie está intentando asesinarme, tengo salud y no he perdido a nadie cercano a mí por el virus. Vivir en España ha sido extraño. El Covid pego duro aquí y el encierro fue bastante intenso, más estricto que en la mayoría del mundo. Pero funcionó. Por ahora, de manera insignificante, las nuevas infecciones han ido a la baja y las restricciones se han aligerado, así que es como si la ciudad estuviera respirando otra vez. No hay mucho tráfico todavía y, por las tardes, cuando tenemos permiso de salir para hacer ejercicio, las calles están llenas de gente. Nadie tiene prisa, son simplemente felices por estar afuera, vivos, juntos. Se siente como una nueva forma de vida en la ciudad.

Pero claro, como el 90 por ciento de mi cabeza está en Estados Unidos, con los policías avanzando en trajes de combate y el virus furioso todavía, entonces la desconexión puede ser extrema. Aquí puedes sentir el alivio como si algo hubiera acabado y hubiéramos sobrevivido, pero me queda claro que nada ha terminado todavía, y lo que sea que esté pasando apenas comienza. ]

DD: Qué difícil está resultando ser testigo del comienzo de un mundo ¿no te parece? Qué difícil aceptar que al comienzo y que no hay manera de movernos de la agonía ¿no crees? Prefiero concentrarme en pelar la fruta para mi semana y detenerme en la belleza de sus colores: una toronja, pienso, no es un producto y sin embargo tiene el color indescriptiblemente atractivo y poderoso que mi biología está ansiosa por devorar, con tal de olvidar este tiempo. ¿No es absurdo que el ser humano crea que puede reproducir el impacto que nos provoca la naturaleza, exterminando la naturaleza? Prefiero perderme en el mundo de una toronja, que echar un vistazo a la verdad. Una fruta también es el mundo infinito y verdadero que uso porque el paisaje global me abruma y me enferma. Pero encuentro una verdad hermosa y terrible en el desierto que describes en Desert Notebooks, Ben. ¿Cómo ha sido para ti ese proceso? Me refiero a ese momento en que das con la verdad: ¿cómo lo procesas?

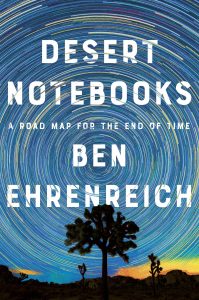

[DD: How difficult it’s turning out to be to witness the beginning of a world—don’t you think? How difficult to accept that we’re at the beginning and that there’s no way to move ourselves outside of this agony—no? I prefer to concentrate on peeling fruit for the week and getting caught up in the beauty of its colors: a grapefruit, I think, is not a product and nevertheless has an indescribably powerful and alluring color that my biology is anxious to devour, if only to forget about these times. Isn’t it absurd that human beings believe they can reproduce the impact nature hits us with, exterminating nature? I prefer to lose myself in the world of a grapefruit than to glance at the truth. A fruit is also an infinite and true world and I use it because the global landscape exhausts and sickens me. But I find a true and terrible beauty in the desert that you describe in Desert Notebooks, Ben. How has that process been for you? I’m referring to that moment when you hit on the truth. How do you process it?]

BE: I don’t know if that moment ever comes. I guess I try to write my way towards it. Desert Notebooks, in a different way from anything else I’ve written, came on like a mission. I talk about it in the very beginning of the book: I was living in Joshua Tree and I went on a walk with Anthony McCann and Kirsty Singer, who are of course friends of yours too, and while hiking up a wash we spooked a couple of owls. They kept flying ahead of us and landing in the rocks out of sight. We kept catching up to them and spooking them again and catching up to them again, and it almost seemed intentional on their part, as if they were leading us further and further into the desert.

A week or so later I sat down to write about it and didn’t stop writing for the next twelve months. That’s only a slight exaggeration. When the writing is going well, that’s what it’s like: you’re chasing a truth that keeps running from you and you have no choice but to follow. There’s no question of catching it, only of running until you can’t run anymore and by then hopefully you’ve circled back far enough that you’ve figured out whatever you needed to figure out, which is never what you thought you were chasing in the beginning. I needed to figure out something about how to go on living and writing in a world that seems to be collapsing around us—that is collapsing, I should say.

Your question surprises me though. I can’t think of many writers who are able to write their way through the real horror as well as the beauty of the world as absolutely head-on as you do, and with as much fearlessness. What is overwhelming for you now that wasn’t before?

[BE: No sé si ese momento llega alguna vez. Supongo que trato de escribir a mi manera sobre ella. Desert Notebooks, a diferencia de todo lo que he escrito, surgió como una misión, Hablo al respecto muy al principio del libro. Estaba viviendo en Joshua Tree y salí a caminar con Anthony McCann y Kirsty Singer, que son tus amigos también, claro, y mientras subíamos por un vado asustamos a un par de búhos. Continuaron volando sobre nosotros y aterrizaron en las piedras fuera de nuestra vista. Seguimos encontrándolos y asustándolos otra vez y encontrándolos otra vez, y casi parecía intencional de su parte, como si nos guiaran cada vez más y más dentro del desierto.

Más o menos una semana después me senté a escribir sobre el asunto y no me detuve por los siguientes doce meses. Es una pequeña exageración, nada más. Cuando la escritura va bien, así es como se siente: persigues una verdad que sigue huyendo de ti y no tienes alternativa salvo seguirla. No hay ni siquiera el dilema de atraparla, sólo de seguir hasta que ya no puedes más y para entonces, a lo mejor diste la vuelta suficientemente lejos como para darte cuenta de lo que sea que necesitas darte cuenta, que nunca es lo que habías pensado que estabas persiguiendo en un principio. Necesitaba darme cuenta cómo seguir viviendo y escribiendo en un mundo que parecía estar colapsando a nuestro alrededor -que está colapsando, diría yo.

Sin embargo, tu pregunta me sorprende. No puedo pensar en muchos escritores capaces de escribir el recorrido tanto por el verdadero horror como por la belleza del mundo enfrentándolo absolutamente como lo haces tú, y con tanta valentía. ¿Qué es tan abrumador para ti ahora, que no lo era antes?]

DD: Hace dos años, estando en Rotterdam para una residencia artística, al medio día en el centro de un barrio adinerado un hombre joven como loco, rompió a patadas la puerta del vestíbulo en el edificio donde fui invitada a vivir por la organización del Festival Internacional de Poesía de la ciudad. Después rompió a patadas la puerta de mi departamento y me empujó contra la pared mientras gritaba Salam Alekum! Cuando me tuvo en el piso se dedicó a patearme la cabeza. Se movió un poco para jalar el cable de un adaptador cuando me levanté y corrí. Nunca supe qué intentaba hacer aparte de patearme la cara. Yo debía estar en un cóctel de bienvenida 3 días después y tenía un ojo cerrado por los golpes, el otro ojo morado, la boca reventada y la nariz negra. Así me presenté. A partir de ese momento los organizadores comenzaron a tratarme como si yo fuera alguien de quien se tenían que defender.

“No todos los mensajes llegan a sus audiencias. A veces asesinan al mensajero, a veces a la audiencia”… :la verdad dio conmigo. Quienes somos: como especie, como sociedad, como “comunidad literaria” ¿No sabía que formo parte del enorme grupo de personas que no tienen derecho a estar a salvo en ninguna parte? ¿Por qué creí que yo era diferente? ¿Porque soy escritora? Pues: Salam Alekum! “Los mundos mueren todo el tiempo”. Es mejor no hospedarse en barrios adinerados europeos, enamorarse para poder pasear de a dos en bicicleta y ante una evidente amenaza de muerte o sometimiento jamás-jamás obedecer. Aunque parezca que estamos obedeciendo hay que estar listos para no-obedecer. En tiempos como este la compañía es vida pura, porque somos millones. Tú sabes: no es lo mismo decir “estamos contigo” a poner el cuerpo entero frente a los militares. Nosotros tenemos el cuerpo puesto frente a los ejércitos encargados del exterminio hace generaciones.

“Hadn’t I known that I form part of an enormous group of people who have no right to be safe anywhere?”[DD: Two years ago, while I was in Rotterdam for an artists residency, at noon in the middle of a wealthy neighborhood, a man, crazy young, kicked in the door to the vestibule of the building where I had been invited to live by the organizers of the city’s International Poetry Festival. Then he kicked in the door of my apartment and pushed me up against the wall while yelling Salaam Aleikum! When he got me on the floor he started kicking me in the head. When he moved a little to pull the cable from an adapter I got up and ran. Other than kick my face in, I never found out what he intended to do. I had to be at a cocktail reception three days later. I still had one eye closed from the blows, the other eye purple, a busted mouth and a black nose, so that’s how I went. From that moment on the organizers began to treat me as if I was someone they had to defend themselves from.

“Not all messages reach their intended audience. Sometimes the messenger is killed, sometimes the audience.” The truth hit me. Who we are: as a species, as a society, as a ‘literary community’—hadn’t I known that I form part of an enormous group of people who have no right to be safe anywhere? Why did I think I was different? Because I’m a writer? Alright then, Salaam aleikum! “Worlds end all the time” It’s best to not stay in wealthy European neighborhoods, to fall in love to be able to ride two to a bicycle, and before an evident threat of death or submission to never, never obey. Even if it seems like we are obeying so that we can prepare ourselves to not-obey. In times like these companionship is pure life, because we are millions. You know this: to say ‘we are with you’ is not the same as putting your whole body out across from the soldiers. We have our whole body out across from armies that have been charged with exterminating us for generations.]

BE: Jesus. You told me about that when it happened, but not the whole story. I’ve always thought that rich neighborhoods were the most dangerous places for writers to spend time, but never quite that literally. And tell me if I misunderstood: the guy was a white European, right? It shouldn’t matter—trauma is trauma—but at the time I understood that he attacked you because he saw you as Arab, or some generic brown other, some ghost conjured by race-sickness. Which is to say, by Europe.

In any case, it is overwhelming. They are kicking in the doors. There’s a line of Walter Benjamin’s, that “even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins,” and the stakes are no less high now than when he wrote that in 1940. They are higher, really: it was 86 degrees in the Arctic yesterday. So yeah, never obey.

One of the things that makes it so overwhelming is the way time appears to be piling up, jumbling, as if the ghosts are too restless to wait anymore and they’re all clamoring and jostling to possess us. The permafrost is melting, revealing ancient bones. Cops kill George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and David McAtee and a statue of a slave trader (aka “philanthropist”) ends up in the river in Bristol. It’s like the last four centuries are all happening right now. The plague is back. And here we are with our fragile bodies, holding hands. Or trying to from six feet apart.

It’s funny, you write some of the most unflinchingly dark poetry I’ve ever encountered, but however overwhelmed you may feel I think of your work as optimistic: always, the violence of states and militaries encounters and destroys soft, vulnerable, impermanent flesh, but somehow it’s the flesh that wins.

[BE: Por Cristo. Me contaste cuando eso pasó, pero no la historia completa. Siempre he pensado que los barrios adinerados son los más peligrosos para que los escritores pasen el tiempo, pero nunca de manera tan literal. Y dime si me equivoco: el tipo era un europeo blanco ¿verdad? No debería importar —el trauma es el trauma—pero en el momento entendí que te atacó porque te confundió con árabe, o algún otro moreno genérico, algún fantasma conjurado por la enfermedad racial. O sea, por Europa.

De cualquier manera es abrumador. Están pateando puertas. Hay una frase de Walter Benjamin, “ni los muertos estarán a salvo del enemigo si éste gana” y los riesgos no son menos altos ahora que cuando él lo escribió en 1940. En verdad son más altos: estuvo a 86 grados ayer en el Artico. Así que sí, nunca obedecer.

Una de las cosas que lo hace tan abrumador es la forma en que el tiempo parece apilarse, revuelto, como si los fantasmas estuvieran demasiado impacientes y empujándose y vociferando para poseernos. El permafrost se derrite, dejando al descubierto huesos antiguos. Los policías asesinaron a George Floyd y Breonna Taylor y David McAtee y la estatua del tratante de esclavos (alias filántropo) terminó en el río en Bristol. Es como si los últimos cuatro siglos estuvieran pasando justo ahora. La plaga ha vuelto. Y aquí estamos, con nuestros cuerpos frágiles, tomados de la mano. O intentándolo a seis pies de distancia.

Qué chistoso, escribes una de las poesías más oscuras e inquebrantables con las que me topado, pero aunque te abrume pienso que tu trabajo es optimista: siempre, la violencia de los Estados y militares encuentra y destruye una carne impermanente, vulnerable y suave, pero de alguna manera quien gana siempre es la carne.]

DD: Exacto: a white, tall holandés guy. Deduje que me confundió con árabe o marroquí por el Salam Alekum que repetía mientras me pateaba. Race sickness, Ben. El mundo tiene piel y esa piel tiene enfermedades. El tiempo se dobla, bien se nota en tu libro, Estos años no pensé tanto en el ataque de Rotterdam hasta que comenzaron los levantamientos anti-racistas aquí. No es normal pero si es importante notar que la persona que me agredió fuera holandés, blanco y por cada patada me gritara un saludo tradicionalmente musulmán. Un saludo que amo. Aparecí en el cóctel de bienvenida con la cara reventada y uno de los patrocinadores holandeses me comentó: eres una mujer dura! Respondí: no. Soy una mujer delicada, hermosa y vulnerable que decide no alargar los momentos desagradables para celebra estar viva. Pero ¿Qué haría una madre al ver la cara racista y asesina de su hijo? Pedir disculpas sin sentirse culpable y odiar en silencio el rostro que le refleja la verdad, discretamente.

El tiempo se dobla. Ser “noble” incluía el derecho a despedazar (y violar en el proceso) a cualquier plebeyo que considerara una “amenaza”. Lo que no puedo comprender es: ¿por qué lo permitimos? ¿Qué es lo que se mata cuando se extermina a una especie, a una raza, a una cultura? Somos incapaces de renunciar al agua tibia y al azúcar refinada. Si la verdad nos despedaza la cara nos retorcemos en nuestro orgullo pensando: ¿cómo se atreven a hacerme esto a mí? abrimos el refrigerador, nos servimos otra rebanada de pastel de chocolate y buscamos las noticias para no perdernos el conteo de los indígenas asesinados por defender la tierra. Lo permitimos tal vez porque durante la infancia si me portaba bien me daban un caramelo como recompensa y si me portaba mal dejaba de existir el caramelo. ¿Quién nos ha entrenado para obedecer, Ben?

[DD: Exactly: a white, tall Dutch guy. I deduced that he confused me with an Arab or Moroccan from the Salaam aleikum he kept repeating while he was kicking me. Race sickness, Ben. The world has a skin and the skin has a sickness. Time folds, as you note in your book. These last few years I hadn’t thought much about the attack in Rotterdam until the anti-racist uprisings began here. It’s not normal, but it is important to note that the person who assaulted me was Dutch, white, and with each kick he yelled a traditional Muslim greeting. A greeting that I love. I showed up at the cocktail reception and one of the patrons of the festival said to me: you are a tough woman! I answered: no. I am a delicate, beautiful, and vulnerable woman who has decided not to dwell on disagreeable moments so that I can celebrate being alive. But—what else would a mother do on seeing the racist and murderous face of her own child? Ask forgiveness without feeling guilty and silently hate the face that, discretely, reflects the truth of who she is.

Time folds. Being a ‘noble’ used to include the right to disfigure (and in the process rape) any commoner considered a ‘threat.’ What I don’t understand is: why do we allow this? What is that’s killed when a species is exterminated? Or a race or a culture? We are incapable of giving up lukewarm water and refined sugar. If the truth disfigures our faces we writhe in pride, thinking, How dare they do this to me? We open the refrigerator, we serve ourselves another slice of chocolate cake and we search through the news in order to not lose count of indigenous people killed for defending the earth. Maybe we allow it because as a child they gave me candy as a reward if I behaved and if I misbehaved the candy ceased to exit. Who has trained us to obey, Ben?]

BE: We inherit it, don’t we? The traumas of our ancestors didn’t die with them. They live on in our fears, and in the fundamental structures of our experience, in what we allow ourselves to perceive and what we exclude, even in how we experience time. I don’t think there is any way out of this trap without a fundamental transformation of how we relate to absolutely everything, the living and the dead and the not-formally alive. The path we’re on only leads to the disaster that we are already experiencing, more genocides, more extinctions. What kind of courage does it take to insist on seeing what we do not allow ourselves to see—everything that writhes, still alive, strong and beautiful, beneath that sick skin of the world?

I’m more and more impatient with any attempt to privilege the literary, to suggest that writers do something special—it’s always writers who insist on this most loudly—but one thing writing can do is help us to peek around our own blind corners. All the trauma, violence, and fear that determine how we relate to one another have always coexisted with courage and generosity and love. If it’s brave, writing can show us that without falsifying or sentimentalizing. It can help us imagine what another way of living might feel like. But living it is something else. It means putting our selves and our bodies on the line.

[BE: Lo heredamos ¿no? Los traumas de nuestros ancestros no mueren con ellos. Viven en nuestros miedos, en las estructuras fundamentales de nuestra experiencia, en lo que nos permitimos percibir y excluir, incluso en cómo experimentamos el tiempo. No creo que haya una salida a esta trampa sin una transformación fundamental en la forma en que nos relacionamos absolutamente con todo, los vivos y los muertos y los no-formalmente vivientes. El camino por el que vamos sólo conduce al desastre que ya experimentamos actualmente, más genocidios, más extinciones. ¿Qué clase de valentía se requiere para insistir en ver lo que no nos permitimos ver—todo lo que se retuerce, todavía con vida, fuerte y hermoso, bajo la piel enferma del mundo?

Cada día soy más y más impaciente con cualquier intento de privilegiar lo literario, de sugerir que los escritores hacen algo especial –siempre son los escritores los que insisten en esto de la manera más ruidosa—pero algo que escribir puede hacer es ayudar a asomarnos a nuestros puntos ciegos. Todo el trauma, la violencia y el miedo que determinan cómo nos relacionamos con los otros siempre ha coexistido con el coraje, la generosidad y el amor. Si es valiente, la escritura puede mostrarlo sin falsificar o sentimentalizar. Nos puede ayudar a imaginar cómo son otras formas de vida. Pero vivir es otra cosa. Significa ponernos a nosotros y a nuestros cuerpos en la línea.]

DD: Lo literario me parece un insulto: reproduciendo la obediencia. No vemos el tiempo. Reaccionamos a lo inmediato y nos parece que ha pasado mucho: cosa de sistema jerárquico. Esta por todos lados. En las universidades nos educan para obedecer. No vemos. Los que asesinaba para avanzar en sus conquistas es lo inmediato. Exterminar es cosa de la inmediatez. Pero más lejos en el tiempo, dentro de nuestra sangre están los minerales extinguiéndose, la flor exótica que nuestros hijos nunca van a conocer y más lejos, dentro de nuestra sangre, nos conforma también la clorofila y los minerales de la tierra, el agua corriendo hacia algún escondite. No vemos el tiempo. Ayer en Ciudad Juárez las Colectivas Feministas prendieron fuego a la obediencia y hoy son perseguidas. Se esconden, como el agua o como el corazón del venado porque: los ancestros son los ancestros.

[DD: The literary seems to me an insult: it reproduces obedience. We don’t see time. We react to the immediate and it seems like a long time has passed: a product of hierarchical systems. It’s everywhere. In the universities they educate us to obey. We don’t see it. They murdered the immediate to push forward their conquests. Extermination occurs in immediacy. But farther back in time, within our blood are minerals going extinct, the exotic flower that our children will never know and farther still, within our blood, chlorophyl and the minerals of the earth are shaping us too , water running toward some hiding place. We don’t see time. Yesterday in Ciudad Juárez the Feminist Collectives lit obedience on fire and today they are being hunted. They are hiding, like the water, or like the heart of a deer because: the ancestors are the ancestors.]

BE: I think we see time everywhere, and that immediacy is not simple, and never was. All of our myths about race have unspoken theories of time hiding inside them: who counts as “primitive” and who as “advanced”? Which countries are “developed” and which ones remain “backward”—or, more polite, “developing”? The narratives that anchor white supremacy depend on implicit notions of time—on progress as an unstoppable force of nature, as sure as gravity, and on a meticulously constructed but nonetheless absurd lineage that connects the ancient Greeks via Rome to the slaver/philanthropists of Bristol to Boris Johnson or whatever, to suburban Proud Boys roaring for race war. Capitalism depends on a fungible hour, on time being capable of valuation and exchange. All of this lives inside us, clicking away the hours and the years, even as we try to fight it there, to find the immediate somewhere other than in our own extermination. But maybe we’re saying the same thing in different words.

And yeah, literature. The word makes me suspicious for the same reasons. It’s a way of delineating power, marking boundaries, cozying up. But you still write, don’t you? Do you remember when Anthony and I came to see you in El Paso and you took us into the desert outside the city and we scurried up through the rocks and then slithered beneath an overhang and had to crane our necks up in just the right place to see the ancient pictographs painted there? I’ve thought about that a lot.

BE: Creo que vemos el tiempo en todos lados, y esa inmediatez no es simple, y nunca lo fue. Todos nuestros mitos acerca de la raza tienen escondidas dentro de sí, teorías no-dichas acerca del tiempo: ¿quién cuenta como “primitivo” y quién como “avanzado”? ¿Cuáles países son “desarrollados” y cuáles “subdesarrollados”—o más gentilmente “en desarrollo”? Las narrativas que anclan a la supremacía blanca dependen de nociones implícitas del tiempo—en el progreso como una fuerza imparable de la naturaleza, tan segura como la gravedad, y en el meticulosamente armado, pero no menos absurdo linaje que conecta a los griegos antiguos via Roma con los esclavistas/filántropos de Bristol con Boris Johnson o lo que sea, hasta los Proud Boys suburbanos rugiendo a favor de una guerra racial. El capitalismo depende de una hora canjeable, del tiempo siendo capaz de valuación e intercambio. Todo esto vive dentro de nosotros, marcando el tic-tac de las horas y de los años, aunque intentemos luchar ahí, para encontrar lo inmediato en algún lado que no sea nuestro propio exterminio. Pero, tal vez, estemos diciendo lo mismo con diferentes palabras.

Y sí, la literatura. La palabra me parece sospechosa por las mismas razones. Es una manera de delinear el poder, marcar límites, acurrucarse. Pero todavía escribes ¿no?

¿Te acuerdas cuando Anthony y yo fuimos a verte a El Paso y nos llevaste al desierto fuera de la ciudad y nos escurrimos entre las piedras y nos deslizamos hacia dentro y nos columpiamos y tuvimos que estirar el cuello justo en el lugar preciso para ver el pictograbado antiguo pintado ahí? He pensado mucho acerca de eso.]

“All the chaos we are living through, the sense a lot of people share right now that time is somehow losing its shape, is its fragmentation, its collapse. But something lasts.”DD: Civilizaciones como los Nahuas (en México) contaban a partir del cero, leían el cielo, crearon la universidad pública, fueron los arquitectos que diseñaron los acueductos cuando en Europa todo era “agua va” y transmitieron sus conocimientos por medio de la tradición oral (por si los documentos desaparecían). No tengo código sino códice genético: los griegos me dan risa. Que el tiempo esté metido en todo como una flecha y no como un transcurso es lo que me hace pensar que no vemos el tiempo. Pisoteamos el tiempo con la prisa. “Clicking away” indeed: estoy totalmente de acuerdo. ¿Serٔá que lo que busca el tiempo es durar? Oh well, tal vez hablamos de lo mismo. Sigo escribiendo. Investigo sobre sadismo y violación: asuntos con raíces totalmente europeas (dicen ahora que son cosas de estos nahuas salvajes -uy, los documentos prueban lo contrario!). Recuerdo los picto-grabados apaches en la cueva de Hueco Tanks, Ben, ese día en mí un descanso comenzó su camino ¿En qué momento nos abandonó el tiempo?

[DD: Civilizations like the Nahuas (in Mexico) counted from zero, read the stars, created the public university. Their architects were designing aqueducts when Europeans were still throwing sewage out the window. They transmited their knowledge through oral traditions (because documents disappear). I don’t have a code: I have a codex in my genes. The Greeks make me laugh. Seeing time as being inserted into everything like an arrow rather than as a passing-through is what makes me think that we don’t see time. We trample time in our hurry. “Clicking away” indeed: I completely agree. Could it be that what time is looking for is to last? Oh well, maybe we’re saying the same thing. I’m still writing. I am researching sadism and rape: affairs with completely European roots. (They’re saying now that they’re a legacy of the savage Nahuas—oy, the documents prove the contrary!) I do remember the Apache pictographs in the cave at Hueco Tanks, Ben. That day a respite opened up a path inside me. At what moment did time abandon us?]

BE: Did it though? I mean are we anything other than time? I don’t believe that cruelty and rape are alien to any human culture. I do think that something happened in the second half of the 18th century that set Europe—and by that I mean Anglo-European North America as well—on a path more destructive than any humans had ever tripped along before, and I don’t think they could have found it if they hadn’t already had a couple of genocides in their pockets. At more or less a single historical moment modern capitalism, scientific racism, and fossil-fuel-based industrialization were all born, litter mates that have never since been separable.

And with them was born this sense of time that I’m talking about, structured at once by a racial logic—the myth of progress—and a capitalist one, that chops the infinite into minutes and hours and human bodies into dollars. Its ascendance has at every step involved enormous violence and erasure, in Europe and everywhere else. We are living the consequences of that. I believe its ascendance has already ended. All the chaos we are living through, the sense a lot of people share right now that time is somehow losing its shape, is its fragmentation, its collapse. But something lasts. The stars keep circling. We age and die and others are born to fight the battles that we left them, so yeah, I’m gonna keep writing too.

[BE: ¿De verdad? ¿O sea, somos algo más que tiempo? No creo que la crueldad y la violación son extrañas para ninguna cultura humana. Pienso que algo pasó en la segunda mitad del siglo dieciocho que plantó a Europa—y con esto me refiero a la Anglo-Europea Norte América también—en el camino más destructivo con el que cualquier ser humano se haya tropezado antes, y no creo que ellos hubieran encontrado ese camino sin antes haber tenido un par de genocidios en el bolsillo. Más o menos en un momento histórico singular desde donde surgió todo: el capitalismo moderno, racismo científico y la industrialización basada en combustible fósil, perros de la misma camada que desde entonces nunca se han separado.

Y con ellos nació este sentido del tiempo del que hablo, estructurado por una lógica racial—el mito del progreso—y una lógica capitalista, que corta el infinito en minutos y en horas y los cuerpos humanos en dólares. Su ascensión está a cada paso involucrando una enorme violencia y borradura, en Europa y en cualquier otra parte. Estamos viviendo las consecuencias de eso. Creo que su ascensión ya terminó. Un montón de gente comparte esta sensación de que todo el caos que estamos viviendo se debe a que ese tiempo de alguna manera está perdiendo forma, es su fragmentación, su colapso. Pero algo queda. Las estrellas siguen su ciclo. Morimos y otros nacen para pelear las batalles que les dejamos. Yo también seguiré escribiendo.]

__________________________________

Desert Notebooks by Ben Ehrenreich is available via Counterpoint Press.