Leslie Jamison Writes Into the Trouble

The Author of Splinters Takes the Lit Hub Questionnaire

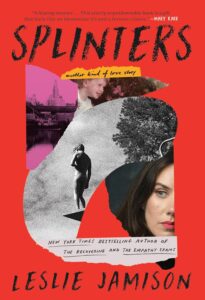

Leslie Jamison’s memoir, Splinters, is available now from Little, Brown, so we asked her a few questions about writing, reading, alternative professions, and more.

*

How do you tackle writers’ block?

Back in my youth, I tackled writers’ block in the time-honored ways: binge drinking and massive amounts of baking. I did so much baking during my MFA days, in fact (largely chocolate chip potato chip cookies, banana cream pies, and Jell-O shots, which is baking, right?) that I actually developed a word for it: procrastibaking. These days I smile fondly when I meet a fellow procrastibaker in the wild: a student who *always* has baked goods to share. Actually, what do I know? Maybe they are hitting every deadline *and* baking up a storm.

These days, I tend to procrastinate in more slyly self-thwarting ways: by taking on even more assignments and projects to distract me from the ones I’m having trouble finishing. I wouldn’t recommend this method. The math doesn’t add up!

*

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

Almost fifteen years ago, my greatest teacher, Charlie D’Ambrosio, told me something so simple and profound about writing essays that it not only changed how I write essays, it changed how I write anything. Honestly, it changed how I lived. He said, “Sometimes the problem with an essay can become its subject.” I think he meant that rather than attempting to answer a question, or resolve it—somehow “get rid of it” so that it wasn’t getting in the way anymore—I could turn the question into the next occasion for rumination, narration, and reckoning, and that this wrestling could illuminate something that would have remained invisible otherwise.

Where has this advice taken me? Instead of skirting around the edges of my abortion, I wrote it. Instead of feeling troubled by the connection between anorexia and pregnancy, I wrote into it. Instead of wondering about the privacy of other peoples’ daydreams, I started asking hundreds of people about their daydreams. Instead of feeling thwarted by the ways in which the concept of “imposter syndrome” had grown ubiquitous enough to lose all meaning, I investigated its ubiquity. It’s basically a way of treating trouble as subject—in content, in process, in self. And what subject could we have but trouble? There is no student I’ve had who hasn’t heard me say this. It’s a piece of wisdom that feels reborn in every new instance of application. I will keep repeating it forever.

*

What time of day do you write?

There’s a time in my life when I might have said: first thing in the morning, before I get onto the internet, before I look at my text messages, even before I talk to another human being. But that time in my life is not this time in my life. This time in my life involves mornings full of fixing breakfast, packing snacks for school, trying to remember the water bottle, trying to coax a six year old out of bed…

But the surrendering of my sacred pocket of time has also brought—as many forms of surrender do—a kind of grace: the realization that writing can happen in so many pockets, in so many places, on so many timeframes. It can happen in the hour (half-hour? Fifteen minutes) of a baby’s nap. It can happen at the departure gate. It can happen in the afternoon, in the last few minutes before you have to leave for pick-up, when you feel the impending horizon closing in. It can happen on the walk to the subway, when you mutter a few words onto a voice memo on your phone.

The point is not that you *have* to turn all this time into writing time—sometimes you just need to text with a friend during naptime! Or you need to buy some last-minute candy before getting on your plane—but that writing doesn’t require the pristine conditions I used to aspire to.

*

What was the first book you fell in love with?

As a girl, I fell hard and wholly and forever in love with The Phantom Tollbooth. It’s about a bored little boy (Milo) who gets a mysterious package in the mail. Already, I was smitten. What if you could get a mysterious package in the mail every time you got bored? This would prove the existence of a loving God if anything could… Milo’s mysterious package contains a tollbooth that delivers him to a magical world he ends up in a pun-tastic world (yes, you can jump right to the Island of Conclusions) that has been divided by an ongoing rivalry between words and numbers. (I knew which side I was on.)

I remember reading about the banquet where you could conjure an entire feast just by describing it—a new life dream—and dawns conducted like symphonies. All the ordinary features of the world—sounds, colors, language, numbers—were turned strange and radiant. I wanted to live in the world of that book. It made me want to make a book that felt like a world to someone else. What a gift.

*

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

When I was a kid, I flirted with a variety of occupations—fashion designer and vet loomed large among them, until I realized I preferred buying clothes and was no good at taking care of animals—but these days I realize that if I were to do anything else, it would be going back to school and becoming a therapist. I love hearing people confess their secrets, their fears, their vulnerabilities; I love hearing someone say a thing she’s never said to anyone.

I feel a deep, almost boundless tenderness towards the endless ways we develop strategies to cope with what we find unbearable. So much of what I’m interested in—empathy, daydreaming, addiction, recovery, intimacy—it’s all the terrain of psychology, but I have a fantasy that as a therapist I wouldn’t just find language for pain, I could actually ameliorate it.

____________________________________

Splinters: Another Kind of Love Story by Leslie Jamison is available now via Little, Brown.