Lee Child and Andrew Child on Discipline, Dread, and Writing Late at Night

And Why There’s No Point in Trying to Organize a Bookshelf

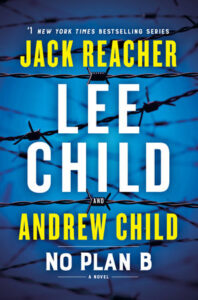

Lee and Andrew Child’s new book, No Plan B, was released earlier today, so we asked them a few questions about writing routine, advice, and influence.

*

What time of day do you write?

Lee Child: I’m ruled by my biological clock, which mandates one unshakeable conclusion: nothing of value is ever achieved in the morning. Typically I get up late and spend a couple of hours moving from a comatose state into something resembling human life. Then I’ll start work about 1 or 2 in the afternoon. I have learned to sense the point when quality starts to diminish, which is usually about 6 hours later, so I’ll stop then. Often I get a second energy peak around midnight, so I’ll do another couple of hours before bed, especially in the later stages when the story is really rolling. Usually a book takes between 80 and 90 working days, spread out over about 7 months.

Andrew Child: My favorite time to write is at night. I like it best when darkness falls and the world shrinks down to the size of the pool of light that spills from my laptop screen. That just leaves me alone with the story I’m telling, nothing to distract, nothing to interfere.

*

How do you tackle writer’s block?

Lee Child: I don’t believe in writer’s block. I think it’s a self-indulgent too-precious mystification of what is, after all, a job like anyone else’s. Do nurses get nurse’s block? Do truck drivers? Of course there are days when you would rather do nothing, but you have to get on. A truck driver climbs in the cab, checks the mirrors, checks the dials, turns on the engine pre-heater, clips the seat belt, starts the motor, and then muscle memory clicks in, and the day starts. Same for writers … I turn on the computer, re-read yesterday’s stuff, and off I go.

Andrew Child: I don’t believe in writer’s block, either. Part of being a professional writer is developing the discipline to sit down and do the work, day after day (or night after night) until the job is done to your satisfaction. There is one note of caution I would strike, though. Over the years I have learned that sometimes when the words won’t flow when I expect them to it can be because my subconscious is warning me that I’m about to take a wrong turn. The important thing is to tell the difference between when you’re just feeling lazy and when you need to avoid making a time-consuming mistake.

*

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Lee Child: The worst is “write what you know”. None of us actually know enough to make a thriller compelling. The better alternative is “write what you feel”—take your fears, your excitements, your desires, your secrets, and blow them up to book-filling size. For instance, I’m a parent, and like all of us I have had those horror moments… you’re at the mall, you glance away, you glance back… and your kid is gone. You feel that intense split-second of dread, and then you see her six feet away, looking in a store window. All good. The trick is to remember that dread, and expand it from a second to an hour, a week, a month.

Andrew Child: The best is “ignore all advice”. Each one of us is the best person in the world—the only person, in fact—to tell our own story so we must trust ourselves to do so in our own unique, distinctive way.

*

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

Lee Child: Not an English teacher, but a physics teacher named Ollie Mathews. He would have us write up our practical experiments, and he insisted on extreme clarity, precision, concision, and brevity. That’s where I really learned to write effectively.

Andrew Child: When I was eighteen, I bought my first car. It was an old VW Bug (or Beetle, as we called them in England). It was beaten up, battered, and broke down all the time, but I loved it. I was driving it home from work one day along a narrow, winding country lane when an executive-type guy in a fancy German car hurtled around a bend, heading straight for me. I stopped. He didn’t. My poor Bug came out of it pretty badly. There was talk of write-offs. Scrapyards. The prognosis was poor but I was confident that with some insurance money behind me all would not be lost.

The problem was that the executive guy got two of his employees to claim, falsely, that they had been driving close behind and had witnessed the accident, and that it was my fault. The insurance companies wound up in court and we were each required to submit a statement that would form the basis of the dispute. It was three against one and I knew that my only chance of getting my beloved Bug back on the road hinged on my ability to set out the facts and conclusions clearly and convincingly, and that’s something I have tried to do ever since.

*

How do you organize your bookshelves?

Lee Child: I try to separate fiction and non-fiction by wall or room, but beyond that I don’t do any organization at all. If you alphabetize, then every time you shelve a new book, you have to move every other book, which seems crazy. Fortunately I have the kind of visual or situational memory that means I know where most titles are … name a book, and I’ll say to myself, oh yeah, that’s in New York, in the living room, in the bookcase opposite the window, second bay from the right, third shelf down, on the left.

Andrew Child: I have tried this many times, in many ways, and nothing has worked. It’s probably more accurate to say that my bookshelves organize me.

_______________________________

Lee Child and Andrew Child’s No Plan B is available now from Delacorte Press.