Learning to Love the Accents of New York (And My Own)

Coco Mellors on “Collecting” Verbal Quirks

“It always makes me laugh when you do that,” said my husband after I’d finished ordering drinks at a restaurant one night.

“Do what?” I asked.

“Pronounce water that way.” He mimicked an American drawl. Wah-der. “You don’t sound like you.”

“But when I sound like me, no one understands me.”

In my accent, water sounds like wot-er, a pronunciation I have learned is incomprehensible to Americans as the substance that covers two thirds of the Earth’s surface. When I moved from London to New York as a 15-year-old because my father got a job there, I did not expect to have trouble being understood. After all, I was relocating from one English speaking country to another. I had grown up on a steady diet of American TV shows set in New York—Friends, Felicity, Sex and The City—and considered myself somewhat familiar with the culture. Yet, despite sharing a language, I quickly found there was much that didn’t translate.

It started with my name. My last name (surname in British) is Mellors. In my mouth it sounds like Mell-ehs, the second syllable swallowed almost apologetically. In American English, because of the hard post-vocalic r, it’s more declarative. Mell-AWS. After just a few weeks in New York, I stopped pronouncing it the British way for good.

Even my first name, Coco, proved a challenge. I was so self-conscious when I first arrived in New York that I wouldn’t open my mouth wide enough to project the “o” sound. I’d whisper my name, lips pursed, in a tiny, squeaky voice that transmogrified my name so fully that it sounded like two of the letter “q” (one of my friends still jokingly calls me “Miss QQ” to this day).

In my early twenties, I had a Danish boyfriend whose verbal quirks never ceased to delight me. He didn’t tidy up, he disciplined the kitchen.

Once I’d gotten past the awkwardness of introducing myself, there was a new hurdle: greetings. During my first week at my new high school, I learned that in America, “how are you?” is often simply a salutation, not a question that politeness dictates requires an answer, as in England. I’d walk down the hallway between classes as the question bounced softly back and forth between the passing students and teachers like a badminton shuttlecock, never answered, simply volleyed to the next person.

How are you?

How are you?

How are you?

When someone asked me, I would stop and fumblingly attempt to reply, disrupting the flow of the hallway entirely.

After introductions and greetings came small talk, another stumbling block. I still remember my clumsy attempt at chitchat with a girl who sat beside me in math (no longer maths) class.

“How was your evening?” I asked her.

“Oh, I got home and passed out,” she said breezily.

“Passed out!” I exclaimed. “Are you okay?!”

She gave me an odd look.

“Yeah I’m fine…”

“What a relief,” I said, nodding manically. “Let me know if you need water or anything during class.”

She turned away from me and I was left with the disquieting feeling that I’d said the wrong thing. Had I not seemed concerned enough for her? It wasn’t until later I learned that in America “passed out” is a term equivalent to “fell asleep,” whereas in England it meant to violently lose consciousness by fainting.

American English, like America, seemed inherently excessive to me. You didn’t just sleep, you passed out. Until the age of about 20, it seemed, you weren’t merely young but a kid. A favorite adjective amongst the students at my high school was belligerent. You didn’t simply get drunk or annoyed or tired, you got belligerently so.

British English, by contrast, is designed to minimize. When I was growing up, “quite nice” was considered a high compliment. Forget being called hot or beautiful, if a boy described you as “a bit of alright,” you were on cloud nine. Recently, a friend of mine casually told me she’d had a “nervy-b.”

“You mean a nervous breakdown?” I clarified.

“I just threw a bit of a wobbly,” she said. “Don’t make a fuss of it.”

Concerned though I was about my friend, I was thrilled by her words. Threw a wobbly! I immediately tapped into the Notes app on my phone.

This habit of making notes started during my first year in New York, first as an attempt to remember phrases that would help me fit in and, later, as a replacement for actual conversation, since I had few friends to talk to. This was, in part, because I was new and shy, but mostly because, during one of my first weekends in the city, I committed a social faux pas I didn’t recover from for the remainder of the school year.

The week after moving I had been invited to a house party, where I’d made out with (or snogged, as we Brits egregiously called it at the time) a strawberry blonde Irish boy in the grade above me, who, unbeknownst to me, had a girlfriend also at our school.

The following Monday, when I opened my locker, a small slip of paper fluttered out. Thinking it would be a missive from my new crush, I opened it with a tremor of anticipation. Written in bubbly cursive were two words: Irish slut.

My first thought was, Can’t they hear I’m not Irish? Maybe, I wondered, this was meant for the strawberry blonde. But, of course, I knew it wasn’t. One immutable fact that did travel trans-atlantically was that only girls could be sluts, never boys. I folded the note very carefully and slid it into my backpack.

Over the course of the school day, I couldn’t stop thinking about it, first with a hot flush of shame, and, later, with anger. At my secondary school in London, I had suffered the inevitable exclusion that seemed to define the group bonding practice of teenage girls, in which one member of a friend group was always being left out—but I’d never been bullied or slut-shamed like this. I fantasized about finding the Irish boy and his girlfriend and flinging the note at them with an imperious flick of the wrist.

“It’s British slut,” I’d say, the t in British thrust like a tiny dagger between my teeth.

In reality, I took the note home and burned it in my bathroom sink, scooping the ash down the drain so no one else would ever see it, then I spent the remainder of the school year avoiding my fellow classmates.

To conceal my lack of a social life from my parents, I fabricated plans with friends on the weekends, then headed to a music venue I’d read about called the Knitting Factory, which didn’t require ID to get in (they’d mark the back of my hands with big black Xs I’d scrub off in the bathroom before heading home). Sets started as early as 5 p.m. on the small downstairs stage reserved for new talent, which meant I could watch two or three bands and still get home by my curfew.

This act of listening and noting has kept me open to the world, even when I have most wanted to close myself off to it.

I didn’t know how to talk to people, so I would bring a notebook and pen to take notes on the bands, pretending I was a music journalist for Rolling Stone (the movie Almost Famous had come out just a few years earlier). After a couple of weeks, I even got up the nerve to interview one of the musicians, a long-haired drummer with the words Fuck Jazz tattooed across his knuckles. He was, in retrospect, not the most obvious choice for a first subject, but I was determined.

“I’m a journalist for Rolling Stone Magazine,” I said, sidling up to him. “Can I ask you a few questions?”

“Aren’t you, like, twelve?” he said.

Despite his reservations, he agreed to speak to me. Those notebooks are long gone, but I can still remember the way he talked. We’re fixin’ to tour real soon. That fixin’, both mundane and musical, thrilled me. I wrote it down and, for a moment, I forgot that I was lonely.

It’s been that way ever since. Some people collect stamps. Some people collect designer bags. I collect fixin’s. New York is the perfect city to cultivate this particular collector’s habit. On my daily subway ride across the city, I could listen to conversations between people from dozens of different countries and regions, all speaking English with their own rhythm and style.

Even after I eventually made friends and built a life for myself in New York, I kept up the habit. In my early twenties, I had a Danish boyfriend whose verbal quirks never ceased to delight me. He didn’t tidy up, he disciplined the kitchen. Since “v” is often pronounced as “w” in Danish, he said things like wampire and West Willage, which is objectively adorable. I swooned over the elegance of a French friend remarking that she was composing dinner for us. I was completely charmed when an Italian coworker told me that his apartment is a stone’s throw away, an idiom for distance that, as far as I know, hasn’t been in casual usage since the New Testament.

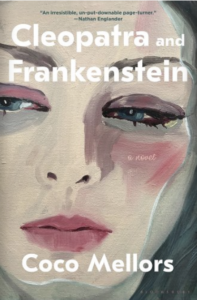

When, at 25, I started writing Cleopatra and Frankenstein about a couple, Cleo and Frank, who fall in love and marry quickly so Cleo can stay in New York after her student visa runs out, I knew their world needed to reflect the globalized New York I’d lived in and loved for the past decade. The characters in my novel are British, American, Danish, Peruvian, Polish, Korean, French, Japanese, among others. I worked on the story on and off for over five years; one of my greatest pleasures during that time was collecting new phrases and idioms to embellish my characters’ dialogue.

This act of listening and noting has kept me open to the world, even when I have most wanted to close myself off to it. I now see the loneliness of those first years in New York as a small price to pay for it. In the place of familiarity, I was given something infinitely more precious for a writer: curiosity. Now, if only I could order a glass of water.

__________________________________

Cleopatra and Frankenstein by Coco Mellors is available via Bloomsbury.

Coco Mellors

Coco Mellors grew up in London and New York. She has an MFA from New York University, where she was a recipient of the Goldwater Fellowship. She currently lives in Los Angeles, California with her husband.