Leanne Shapton Talks Ghosts and Guardian Angels

With Drew Broussard and Christopher Hermelin on So Many Damn Books

On So Many Damn Books, Christopher Hermelin (@cdhermelin) and Drew Broussard (@drewsof) discuss reading, literature, publishing, and their ongoing failure to get through the TBR pile (all with a themed drink in their hands).

This week, Leanne Shapton drops by the Damn Library for a spook-filled episode to discuss her new collection, Guestbook: Ghost Stories, along with Christmas wrapping paper, first stage appearances, tennis, hauntings, and the wonders of Miriam Toews’ new novel, Women Talking.

*

Drew Broussard: I love the idea of creating and reinforcing the idea that ghosts don’t just have to be spooks that pop out and scare you. There are stories in this book that are some of the scariest stories I’ve ever read. After creating this book, how would you define a ghost?

Leanne Shapton: It’s funny that you bring up Was She Pretty? because I begin that book with a Kierkegaard quote, and I could go back to it and say this is what a ghost is. It starts, “What is it that binds me? From what was the chain formed that bound the Fenris wolf? It was made of the noise of cats’ paws walking on the ground, of the beards of women”—those don’t exist—“of the roots of cliffs”—those don’t exist—“of the grass of bears, of the breath of fish, and of the spittle of birds.”

All these things that are invisible. “I, too, am bound in the same way by a chain formed of gloomy fancies, of alarming dreams, of troubled thoughts, of fearful presentiments, of inexplicable anxieties. This chain is ‘very flexible, soft as silk, yields to the most powerful strain, and cannot be torn apart.’”

These are still my ghosts. In this case, it was the haunting of the ex, the person you could never measure up to. And in this case, it was a failed marriage or a dream you let go of. It is still these things that bind you, that haunt you, but don’t exist.

*

“Some people call it a guardian angel. Scientifically, it is a reported and provable thing.“

Christopher Hermelin: How did Billy Byron haunt you? It’s this tennis story, and you’re following the career of this tennis player who is very talented but haunted.

LS: This was a mix of a few preoccupations of mine. One of them goes back to the Arctic. One of the people I met in the process of reporting the story of John Franklin was an old colleague of mine from a Canadian newspaper called John Geiger, and he was the president of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. In addition to having this position, he also has an interest in the spiritual. Not entirely the paranormal but he wrote a book called The Third Man Factor, and it’s about the sensed presence. The sensed presence was something that these explorers—because of his background in the Explorers Clubs and the Geographical Society—Shackleton, Lindbergh, and maybe even Earhart all had records in their logs of experiencing a sensed presence when they thought they were going to die. It’s a bit of a guide. Some people call it a guardian angel. Scientifically, it is a reported and provable thing.

I was talking to John, and I got the idea of the tennis player because of my love for the story “The Rocking Horse Winner” by D.H. Lawrence. It’s one of my favorites, and you could call it a ghost story or a horror story. This boy is haunted by the sins of his parents, in this case the mother. He hears these voices in the house saying there must be more money, and he wants to help. That gets him into deep trouble. I love the idea of one of these sensed presences being less than benevolent. In John’s book, they are benevolent and very linked to the imaginary friend, a coping mechanism that sometimes the child will have when there is trauma but an adult will have if there is trauma too.

Also, I was a jock for a lot of my life. My wanting to use that landscape of sports and how pure winning and losing is, I always loved, so I had Billy Byron have a not-so-benevolent sensed presence. I really wanted to play how I could tell that story with words and pictures. I wanted to cast and shoot it, but I didn’t have enough time or money. Those pictures are pulled from a lot of places. I just tried to get tennis players in moments of defeat or crisis covering their faces so they looked like the same person. I hope it worked.

DB: What comes first? What’s your process for a kernel of a story and then pictures and the scope that you’re going to shoot this series or create this story—how do you put these things together?

LS: I see myself as a writer who can lay out pages. If I can’t write it straight . . . I would have wanted to write out Billy Byron . . . I could hear in my head those stories and see them from beginning to end. The way I write is through layout, through pictures and captions. Some of the stories in the book are just accounts, and those are the ones where I’m sort of following the traditions that ghost stories are told second-hand. Those I felt I needed in the book for mixed consistency and pacing these moments where they were just text. That aside, I will just try to see what the best and most efficient telling of the story given my limitations, because I am a limited writer. I am not trained as a real prose writer. I didn’t go to Iowa. I really try to go, “How am I going to do this,” and not, “How do I want to read this?” . . . I have to just try to color it in. I’ll usually get an idea and know how it sounds or how it looks. If I know how it looks, it starts with the layout, and if I know how it sounds it starts with the story and the idea that I then color in.

*

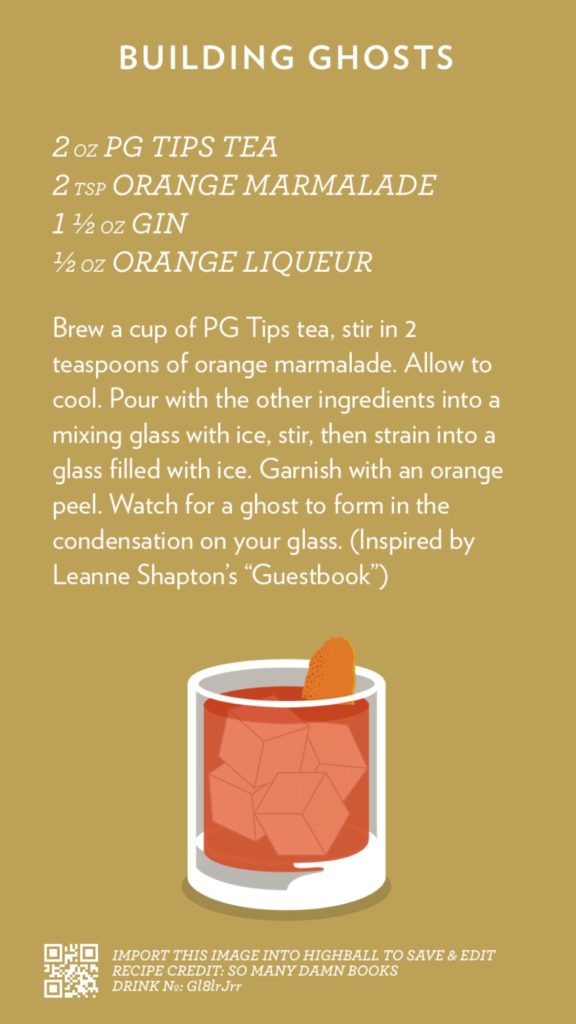

THIS WEEK’S DRINK

So Many Damn Books

A blessing, a curse, a podcast. est. 2014. Christopher (@cdhermelin) invites folks to the Damn Library to talk about reading, literature, publishing, and trying to make it through their never-dwindling stack of things to read. All with a themed drink in hand. Recorded at the Damn Library in Brooklyn, NY.