Lauren Groff on Writing Her Own Robinson Crusoe

This Week on The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

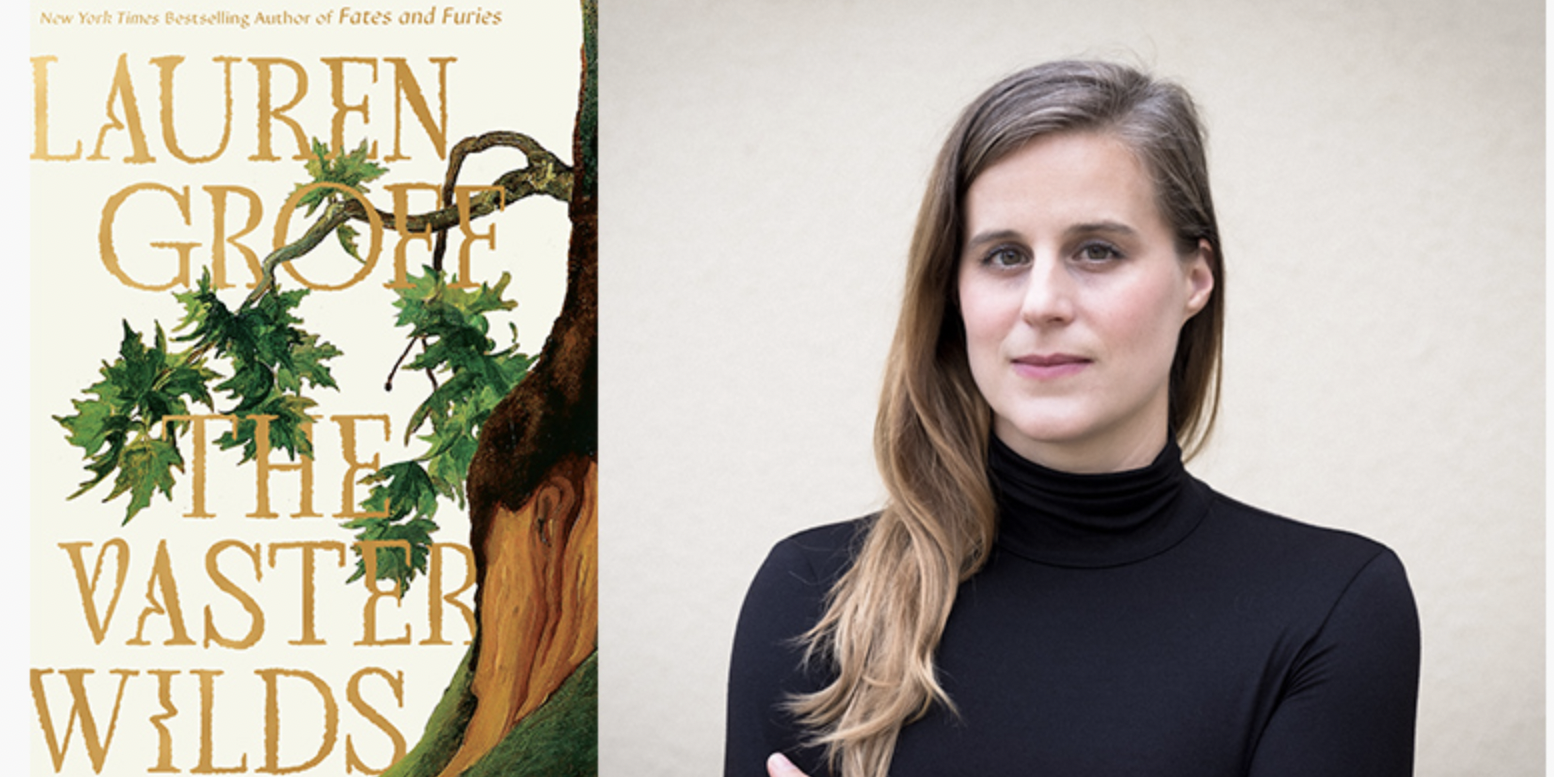

Books & Books recently had the pleasure of hosting three-time National Book Award finalist and best-selling author Lauren Groff, presenting her new novel, The Vaster Wilds. The New York Times calls it “a lonely novel of hunger and survival.” The brilliant Groff reads from her adventure novel and answers questions from her audience of fans. This new episode of The Literary Life was recorded at Books & Books in Coral Gables.

From the episode:

Lauren Groff: So I thought, oh gosh, well maybe my Jamestown idea has another part to it. Maybe I could write a female Robinson Crusoe. And then I remembered –and this is the third part of the book that actually came together and exploded into an idea– I remembered captivity narratives, which, if you don’t remember ninth grade history, like, don’t worry about it.

My, my tenth grader doesn’t either. But captivity narratives are these astonishing American texts. I know they’re, I mean, they’re from all over the world, but the ones that we really study tend to be American. And they are from the eruption of colonization and the Native peoples. So what happens in captivity narratives is that it’s the story of someone on the frontier being seized by the Native Americans, held for a time and then ransomed back.

And usually these texts were as told to religious people. So Increase Mather, a very famous early preacher, and Cotton Mather, his son, who was responsible for the Salem witch trials, loved to collect these, these captivity narratives, and publish them. The most famous one that we know of is Mary Rawlinson’s Captivity Narrative, which is actually an amazing text just to read.

Uh, harrowing, interesting. It’s all… used for propaganda purposes. So the propaganda purposes of captivity narratives was in order to justify and make seem godly, in a way, the expansionof the Europeans into North America. It was a way of saying, look at these poor, primarily white women who have been captured. Look at how evil the people are who captured them.

So they’re really problematic, right? As texts, they’re really complicated and they really do tell a lot about the mindset of the people at the time, who are writing them. And I thought, well, after I wanted to write a female Robinson Crusoe, wouldn’t it be great if I was also writing a captivity narrative?

The Literary Life

Mitchell Kaplan has been a bookseller and has owned the independent bookstores Books & Books for over 35 years. Enter the Literary Life where every week you’ll hear candid conversations with Mitchell and his guests, including Dave Cullen, Min Jin Lee, Lisa Lucas, Tayari Jones, Tina Brown, and Pete Souza.