Laura van den Berg on the Horror Films That Inspired Her New Novel

Lurking in the Shadows of The Third Hotel

The Third Hotel is out now from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Les Revenants

Les Revenants is an unconventional zombie movie—and a favorite of mine. In a French town, the dead come back to life without any explanation. Because the returned don’t seem to pose a threat, they are reintroduced into society. The first time I saw Les Revenants I was on the edge of my seat waiting for the returned to start feasting on their beloveds, but the obvious frights never come; instead a more nuanced and far more unsettling transformation occurs. The dead exhibit a mysterious array of medical symptoms and before long it becomes evident that they are responding to forces that exist beyond the grasp of the waking world. The presence of the undead pushes the living into pretty strange terrain as well, as Les Revenants moves deeper into its meditation on the ways grief can warp and disorient the living. A central plotline concerns a woman and her returned husband, and given that the mystery surrounding the circumstances of his return is never fully pierced, Les Revenants became an important model for The Third Hotel.

Halloween

While working on The Third Hotel, I decided to revisit Halloween and was reminded what a master class the movie is in the art of anticipation. Death has come to your little town, Dr. Loomis (Michael Myers’s doctor) says at one point and indeed it has, though it takes a while to get there. The movie is a mere 86 minutes and—save for the opening sequence, which delivers Michael Myers’s violent childhood history—no murders occur for approximately 55 minutes (!). Instead we get the gradual descent of night and the narrowing possibilities of space: the way wide leafy suburban boulevards give way to a locked laundry room; the shadowed inside of a car; a closet. We get Michael Myers’s methodical stalking, the relentless assurance of his coming violence—by car, on foot, the glimpse of a mask. His panting breath. John Carpenter’s infamous, almost unbearably tense score. I aspired for The Third Hotel to feel increasingly claustrophobic as the narrative progressed, and studying Halloween definitely made me think harder about the cinematic possibilities of space (there’s even a closet homage halfway through the novel).

An aside—I love how self-referential horror is as genre, and it was fun to think about how to incorporate that quality into The Third Hotel. For example, the name Loomis, as in Dr. Loomis, returns in Wes Craven’s Scream (one of the killers is named Billy Loomis), which in turns features, in the house party scene at the end, characters watching Halloween. And while we’re at it let’s not forget Samuel Loomis, from Psycho.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, which takes place in a fictional Iranian town called Bad City, is quite possibly the most stylish horror movie I’ve ever seen. Shot in black-and-white, the movie playfully incorporates different genres (vampire movie, Western, revenge narrative, a very unusual love story) and layers of mood (retro, noir, goth). I found the film’s hybridity striking and inspiring—I love work that intermingles genres that might seem, on the surface, to be unlikely companions. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night nods to past classics and is also absolutely singular, especially as a beautifully, blazingly feminist horror text. The hypnotically rich atmosphere—from the soundtrack to the industrial landscape to the use of shadow and light—is also high on the list of things I admire about Amirpour’s film. Atmosphere is so important to me on the page, as both a writer and a reader. Atmosphere is an invitation, an invisible presence felt viscerally in each line, a force that makes the fictive world vibrate with a particular kind of energy, that shapes the rules of that world even. Amirpour has such exceptional command over her material, and the atmosphere it generates, that when I watch A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, I get the sense that, with each frame, she is saying exactly what she wants to.

The Babadook

With The Third Hotel, I was interested in exploring the idea of manifestation, a popular trope in horror films (i.e. a character’s psychological duress becomes fuel for a terrifying supernatural happening), which leads me to Jennifer Kent’s wholly chilling The Babadook. The protagonist, Amelia, is a widow raising her troubled son on her own (her husband was killed in a car accident, driving Amelia to the hospital while she was in labor). After reading her son, Sam, a storybook about the Babadook, Sam, who is already preoccupied with battling imaginary monsters, begins insisting that the Babadook is real. As grisly visions, menacing calls, infestations, nighttime sounds that would drive me screaming into the street, and evidence of the Babadook accumulate in the house (plus ill-timed visits from child services), Amelia looses her mooring and the threat of violence escalates. If Sam was a challenging character to weather in the opening scenes—I confess to being fairly exhausted by him within about three minutes—the tables are turned in short order, as a bewildered and terrified Sam works to console, and then survive, his freshly terrifying mother (all that monster-slaying practice turns out to be pretty handy).

The film is incredibly tense well before the Babadook kicks its menacing into full gear. Amelia is exhausted and grieving, and Sam’s issues, and subsequent social exclusion, has left them both isolated. They are two characters under tremendous pressure with no outlets for release. The Babadook is a monster movie, yes, but the real power comes from its exploration of Amelia’s guilt and rage and fear, her anxieties about her capacities as a mother. And because the Babadook is never quite fully revealed to viewers the ambiguity around the true source of the terror remains intact. The Babadook is also something of a cautionary tale about the danger of denying one’s own emotional reality—of saying it’s fine, it’s fine when things are anything but okay. If the monster’s presence can’t be willed away sometimes the only answer is to let the creature in.

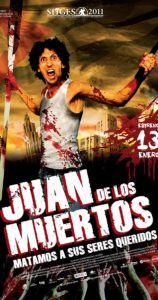

Juan de los Muertos

Any list of horror movies of importance to The Third Hotel would be very incomplete without Alejandro Brugués’s Juan de los Muertos, which was regarded by many critics as the first Cuban zombie movie and provided the initial inspiration for the film-within-my-novel. After a zombie apocalypse overtakes Havana (an early sign of trouble occurs when the titular Juan and his sidekick reel in an undead corpse while fishing), Juan spots an opportunity to embrace a little capitalism at the end of the world. He begins a service where he and a small crew of survivors can be hired out by the living to dispatch undead family members, a venture that proves to be very successful and also very dangerous. As the title might suggest Juan de los Muertos is as funny as it is bloody, and it’s also a movie that contains a great many layers, including a powerful look at the pains and costs of being among those who have survived. You’ll be so busy covering your eyes as the blood starts flying and laughing at the irreverent jokes that it can easy to miss the potent social commentary threaded throughout Juan’s quest through a ravaged city—but, like any good horror movie, Juan de los Muertos has a multitude of stories to tell; zombies is only one of them.