My mother saw her first psychic when she was a young woman, 19 or 20, in her hometown of Nashville. Her father drove her over to a place in East Nashville, where she remembers a dramatic-looking woman (big earrings, a clamor of bracelets) swinging open the door. She can’t remember why she sought the help of a psychic in the first place, only that this one had come recommended by her hairdresser, whom she trusted. If pressed, my mother imagines she was seeking help with boy trouble—back then, that was always the story.

When I express surprise that my grandfather was a willing participant—he was a dairy farmer and not the type to put much stock in the otherworldly—my mother reminds me that he loved to drive. He would take me on any kind of adventure if a car was involved. My mother can’t recall what she and her first psychic discussed, and while she never went back to this woman in East Nashville, nevertheless, the visit opened for my mother a portal into a world of mediums and predictors, a world that would captivate her for many years to come, a world she would pass on to me. When I ask my mother for a why, she tells me—People have been trying to make sense out of chaos for millennia. That is what you hope a psychic can do.

*

Writing a novel can feel like an attempt to make sense of chaos, so perhaps it’s not a coincidence that I got my first tarot reading in Key West, during a summer spent at an artist’s colony. I was struggling mightily with my first novel, and at the height of my creative troubles, I found a man named Ron Augustine during the sunset celebration at Mallory Square, after I had read an article about him in National Geographic. Ron Augustine was easy to spot because he conducted his readings on the pier, holding a very large white parasol in one hand and turning the cards with the other. That summer marked six years of work on my first novel, and instead of the breakthrough I longed for, I kept hitting impasse after impasse. The book was under contract: I was starting to think I would never finish and would have to repay the advance. I told myself that I could live with either outcome; somehow I would figure out a way forward, even if I had to give the money back. I just wanted someone to tell me how it was all going to end. I could not stand the not knowing for a moment longer.

I wondered what would have happened if a stranger with a parasol had not told me exactly what I needed to hear.I waited in line to speak with Ron Augustine, and when it was my turn, I sat in a folding chair across from him. He laid the cards out on a small table and surveyed my fates. He told me that I had been engaged in a tough struggle for years and now that struggle was almost over. I was close, but I needed to keep pushing and I needed to be braver—braver than I had ever been before. I paid him, thanked him, and then cried while waiting in line for fried clams.

The next morning, I woke at dawn and set out for the ocean. From a dock, I dove into the water, and when I came up for air, the solution was right there, clear as a familiar song. I returned to my studio and deleted the last hundred pages of my novel, the section that had been giving me the most difficulty. I threw out my flash drives and emptied the trash on my laptop; I worked to eradicate any trace of those old pages.

This was what I understood “brave” to mean: release what is not working and what will never work and make something new, something better, in that empty space. Deep down, I had wanted to make this move when I first arrived at the residency, but I was too scared. I rewrote those hundred pages in three weeks. I submitted the book to my editor on time; I did not have to repay the money after all. All the while, I wondered what would have happened had I not thought to seek out Ron Augustine, if a stranger with a parasol had not told me exactly what I needed to hear, at the exact right moment in time.

*

My mother believes mediums are better with the past than with the future. As an example, she cites a visit to Cassadaga, the famed medium community in Florida. In the 70s, my mother saw a psychic in Cassadaga who told her that her first cousin’s wife had committed suicide—true—and that this dead woman now had a message for my mother. The problem is: Most people don’t see psychics for information about the past.

In Cassadaga, the information about the suicide was impressive, a testament to the medium’s powers, but it was also information my mother already knew. Most people—certainly my mother, certainly me—are hungry for the predictive. For a glimpse into the future, which is in a sense a glimpse into the forbidden, for to know our own futures is a kind of power we are not supposed to have.

*

The best medium my mother says she ever saw was a man in California—except she never actually saw him. He was a telephone psychic, and for a period of five years, she spoke to him every four months. During this period, my parents were going through a painful, lengthy divorce, and my mother swears this man in California could predict what would happen in the courtroom, what my father’s next move would be. My mother says that she hadn’t wanted to hear things you could hear from your therapist or a friend—hang in there, one day at a time. She had wanted answers. She had wanted to know.

Alas, the story of the man in California does not have a happy ending. He was diagnosed with early onset dementia and lost his powers. My mother consulted a string of psychics afterward, hungry for the answers to keep coming, and felt that they all failed her.

*

A family story: My father was said to have ESP for a time, back when I was still a small child. Not psychic abilities per se, but a sixth sense, an ability to see several moves ahead—to predict how the weather would turn, what a person was going to do. Then one morning he was carrying an armful of dress shirts down the stairs. He stepped on a sleeve and somersaulted to the ground. The fall knocked him out, dislocated his shoulder, and after he came to in the ER, he never had ESP again.

The bottom line: Powers of all kinds are delicate. You never know what will make them leave.

*

In 2014 I was on the road a lot. At some point, I decided to embark on a little project where I would visit tarot card readers in each new destination. Probably I should have sought out a therapist instead, but I wanted my own answers and this project seemed like a shortcut to getting them.

At the start of a reading, I always wanted to go straight to the bad stuff.At the time, I was bouncing around between various campuses, always between home and some other place. My husband and I were spending too much time apart. My father was ill. Out of nowhere, or so it seemed, I had been beset by overwhelming flying anxiety. I was in a state of perpetual motion, moving too fast to absorb much of anything.

Over the course of this experiment, I had tarot readings in Portland, Maine; New Orleans; LA; and Perth, Australia. The longest reading: 60 minutes. The shortest: 10. All the readers were women except for Ron Augustine in Key West. The readings cost somewhere between 10 and 60 dollars, usually paid in cash. At the start of a reading, I always wanted to go straight to the bad stuff. That is the fiction writer in me, I think: Let’s get right to the trouble.

In LA, the tarot reader told me a friend from childhood recently came back into my life and that this person did not wish me well. Be careful, she warned. I nodded because I did not know how to explain that I had very few friends in childhood and I was not in touch with any of them.

In Perth, the medium’s address was a storefront for a crystals shop, the air inside clouded with dust and incense. When I told the owner I was looking for a reading, she bolted the front door and led me down a flight of narrow, winding steps, the ceiling treacherously low. I followed her into the basement and then another small room with a cement floor; she bolted this door behind us too. If she had been a man, I would have run screaming. We sat at a small table; she lit a cigarette. She chain-smoked through the entire reading and described the state of my life with alarming accuracy. At the end, she told me that I knew what I needed to do, and when I was ready, I would do those things.

During this experiment, I went to Chicago but did not get a reading. I only had so much time and decided to go to a museum instead.

*

Having felt misled by psychics during her divorce, my mother remains disillusioned with the whole enterprise. I’m done with them, she’s told me time and time again, and yet I recently learned her disillusionment did not stop her from phoning a psychic recommended to her by a fitness instructor. This psychic was located in East Nashville too, not far from my mother’s first encounter decades earlier, and she reports that absolutely none of his predictions have come to pass.

*

Aside from the man in California, my mother now thinks the most effective mediums she ever spoke to were not meant for people, but for animals. She reminds me of a family friend’s story: They had a horse who started misbehaving, for reasons no trainer or vet could understand. Finally the family friend called a horse psychic, who reported that this horse was being driven mad by a ringing sound in her stall, like an alarm that wouldn’t quit. What ringing? they thought at first, and then they remembered: The horse’s stall had been changed, just before the bad behavior started, to next door to the barn office. The owners went and stood in the stall, and every time the office phone went off, a shrill ringing sounded out. Soon they could see why the phone had been driving the horse mad.

To know our own futures is a kind of power we are not supposed to have.I wonder if the difference is dealing in the now versus attempting to predict the future, I say to my mother. People call animal communicators because their dog won’t stop barking at the mailperson or because their cat seems depressed. The aim is diagnostic, not predictive, and perhaps the predictive is the problem with the whole medium enterprise, when it comes to people—or the problem with the particular feature of my inheritance. My mother and I want a key to the future. We want exactly what human consciousness is not designed to offer. If we know, we think we can prepare. A practical impulse, in some ways, if executed through a highly impractical means.

*

I don’t feel disillusioned about mediums in the way my mother does, but in an effort to save money and to take fewer shortcuts, I haven’t spoken to a psychic or tarot reader in a couple of years. My flying anxiety worsened, and then anxiety began to take root in other areas of my life, and my father got sicker—so I sought out a real therapist and began to do the hard work of dealing with the past and the now and the future.

One point of clarification—I haven’t consulted a medium meant for humans in a couple of years. This spring, I consulted an animal communicator for my dog, in an effort to understand why my otherwise friendly running companion would bark at runners when he passed them on the trails. According to the animal communicator, my dog finds barking at runners “highly satisfying”—he knows I dislike this behavior and yet he has no plans to change. Some things are too fun to give up, he reportedly told the animal communicator. And when you put it that way, who could blame him? My dog also mentioned that he enjoys getting up on all the furniture except for a chair in the bedroom—the legs wobble and he slides around, once he even fell, a statement that startles me to my feet with its accuracy.

*

When I press my mother for specifics on the subject of psychics, she admits that she threw out all her notes from her readings during her last move. I never took notes during my own readings, even though I have a bad memory, another trait I share with my mother. But I keep circling back to the idea of the diagnostic versus the predictive, the now versus the future—and how maybe it’s not so much that we want to know the future, for to truly know could be a grim and burdensome power, but rather we want confirmation for what we suspect might be true.

Making big decisions can be so lonely, after all, and there is a special kind of power in a stranger telling you what you already know, in the deepest well of yourself. Just keep going. You know what you need to do. To hear a stranger, whether it be because they are a very canny reader of people or because they are in conversation with the divine, repeat back to you the truth that you have been hesitant to trust, the truth that you have tried to ignore or maybe even bury—but can’t for a moment longer.

_________________________________

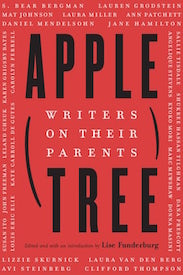

Excerpted from “Predictions,” an essay in Apple, Tree: Writers on Their Parents, edited by Lise Funderburg, by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. ©2019 by Laura van den Berg.