Laughing At Evil: When Charlie Chaplin Brought Hitler to the Big Screen

Scott Eyman on the Making and Legacy of The Great Dictator

Chaplin’s optimism about The Great Dictator was confirmed by the critics. Variety said that “the picture has had much advance publicity, and the curiosity aroused in its connection no doubt is second only to that which was built up for Gone With the Wind.”

President Roosevelt was invited to the opening in New York on October 15, 1940, but couldn’t attend and sent FDR Jr. The opening night, Variety said, had some rocky moments, because the audience had been misled by “some of the very amusing still photographs.” The crowd, said the paper, was “cool to the Chaplin effort and hesitant to respond to its theme, except in the hilarious farcical scenes. The first audience reaction was that Chaplin should stick to his funny hat, cane and shoes and leave world politics to the politicians.”

But Variety ultimately realized that Chaplin had, against all odds, accomplished something remarkable: “The Great Dictator is one of those milestones by which films since their early, faltering days have been led to renewed inspiration and realization of hidden opportunities. In The Great Dictator, Chaplin has employed the full force of the screen’s expressive power to crystalize the timely and encouraging idea that the world is only half-crazy and that sanity has not completely fled from human experience.”

Chaplin’s silent features have a blithe momentum, with most sequences carefully building toward the climax. No matter the difficulties encountered in production, in the cutting room Chaplin was ruthless about narrative. He understood that flow was crucial, and the silent features mostly feel seamless.

Chaplin’s indifference about what other people thought tended to make his films better, while considerably complicating his life.Chaplin’s sound pictures are a different matter. Their rhythm is baggier, the running times are extended, the characters less firm. Mostly, this is because he saw sound as lending itself to political and social comment alternating with the expected amounts of comedy, which meant he had more to pack in. The Great Dictator is a particularly audacious mixture of satire, slapstick, tragedy, propaganda, and music hall jokes out of the Karno days:

“How’s the gas?” asks the pilot of a falling plane.

“Terrible, kept me awake all night,” replies Charlie.

The film also provided yet more evidence of Chaplin’s psychological grasp of character that coexisted with his protean acting skills. His Adenoid Hynkel is a comic X-ray of the authoritarian personality: endless vanity fueled by pathetic insecurity that can only be quelled by absolute obedience. As Hynkel, Chaplin captures both howling fury and an almost coquettish wheedling, all communicated through a soft English diction that indicated Chaplin had done a lot of work ridding himself of his working-class accent.

“He didn’t just scream and bawl,” said Alistair Cooke of Hitler’s speeches. “And he also had this slightly fancy toss of the hand, you know. He didn’t always give the full rigid salute. I remember Chaplin telling me about the dance that he was going to do with the globe…which did seem like a poetic extension of Hitler. But Hitler also made very delicate gestures with his hands. Chaplin had the most beautiful, very small hands, you know, like ivory knick-knacks. It’s the only film I know that gives this side of Hitler.”

Many critics have objected to the final speech, in which Chaplin steps out of character and addresses the audience as Charlie Chaplin—the twentieth century’s emblematic comic personality using his skills to delegitimize the century’s greatest threat to freedom, to art, to civilization: an apostle of compassion engaging in mortal combat with a promulgator of hate. Many people then and now consider the speech little more than sentimental utopianism, but Chaplin’s passion is overwhelming:

“Greed has poisoned men’s souls—has barricaded the world with hate—has goose-stepped us into misery and bloodshed. Machinery that gives abundance has left us in want. Our knowledge has made us cynical; our cleverness hard and unkind. We think too much and feel too little. More than machinery we need humanity. More than cleverness we need kindness and gentleness. Without these qualities, life will be violent and all will be lost.”

True then, true today.

Variety reprinted the speech in full, and did an extensive interview with Chaplin in which he tried to deny that he was speaking as himself rather than his character. “There have been objections,” Chaplin said, “that the speech was not in keeping with the general practice of ‘good motion picture making.’ I don’t agree. Others have complained that it is out of character. I don’t agree on that either.

“It is not as unbelievable as they think to have the meek barber make such a speech. I could have finished it with a cliché, but that would have been still harder to believe. I could have had him triumphant, but that wouldn’t have been true to life. I could have had him kick the storm troopers out of his way and escape, then showed him with Paulette Goddard in the setting sun, approaching America, the land of freedom and hope. But if you want to get on the subject of credulity, then they’d have the immigration authorities to deal with before they got into America.

“It seems entirely conceivable to me that the little barber, pushed into the position he was, could have made the speech he did. It was all the pent-up emotion resulting from the persecution he and those he loved had been subjected to. He was in a stage where he was semi-hypnotized by the situation. He was no longer the barber, nor was he the dictator, nor was he me. He was a combination of all three.”

Chaplin’s own take on the reviewers who objected to the final speech was that they had “a perceived notion of what I was going to do, based on what they had seen in the past. They had a groove all planned for me and I didn’t fall into it. I felt I had to do something different, because times are different. There are grave things happening in the world and I wanted, in my way, to reflect them. I don’t pretend to be a propagandist, but I felt I must cry out against persecution….

“The world isn’t a pleasant place in all its aspects, and there’s no reason to make it appear that way in a picture. Furthermore, what critics forget is that I try to create enjoyment by creating emotions. I have never limited myself to the single emotion of laughter. I have attempted to stir up all sorts of emotions. The more varied the ones I create, the more enjoyable the picture.”

Geraldine Chaplin believed the final speech to be one of her father’s finest moments: “He steps up to the microphone, he’s a little barber and then he’s pretending to be the dictator. Then the camera comes in close and he starts speaking and the transformation—suddenly he’s no longer the Jewish barber, he’s no longer the dictator, he becomes Charles Chaplin speaking to the world. The way his face changes—I’ve watched that a million times. He becomes Charles Chaplin, without taking the makeup off, without anything; suddenly his face, it becomes older, you see the lines on it, and you see the man come out.”

The film opened in London in December 1940—the height of the Blitz. The critic C. A. Lejeune opined that the film was “uneven…harsh at some moments, sentimental at others, brilliant, even noble in many parts. The ghost of every trick that Chaplin has ever played is in the film somewhere. Watching it, your memory ranges back to The Pilgrim, The Kid, Shoulder Arms, even further to the plain, downright days of custard-pie and mallet.”

The Great Dictator has retained its hold on audiences, and remains a popular picture, perhaps because its subject is perennially relevant.There were criticisms that Chaplin had singled out dictators of the right, while leaving out dictators of the left. “I’m not working in the political arena,” he said with a straight face. “I’m working in the human arena. Had I included Stalin, I would surely been getting into politics because there was no reason to include him from the standpoint I was taking. He may be a dictator, but he’s not persecuting helpless people because they are Jews, or Chinese, or Mohammedan, or because he doesn’t like the shape of their eyebrows.” (History has since proven that Stalin was, among other things, a vicious anti-Semite and homophobe. Chaplin was completely wrong.) Variety noted that Chaplin spoke with “a curious mixture of humbleness and the blazing conviction that he is right, his critics wrong, on all but one point—the picture’s length. He said he thinks he has culled from it every possible bit of footage without removing whole sequences. He’s anxious, he averred, to cut more if he can be shown how it can be done.”

In retrospect, it can be seen that The Great Dictator was the high-water mark of Chaplin’s political and social relevance. Everybody in Hollywood thought Chaplin was insane to make an antifascist film at a time of rampant isolationism. It was an opinion shared by Sydney, who believed the film was commercially dubious as well as politically dangerous. But Chaplin’s indifference about what other people thought tended to make his films better, while considerably complicating his life.

Released a year before Pearl Harbor, The Great Dictator portrayed Jews as an oppressed minority, served as a passionate clarion call for intervention, and, in Chaplin’s inspired burlesque of Hitler, was often uproariously funny in the bargain.

The Great Dictator ran for fifteen weeks in New York—a huge commercial achievement. Produced for $1.4 million, it returned rentals of $5 million to United Artists, producing a clear profit to Chaplin of about $3 million, despite the fact that most of Europe never saw the picture until after the war. The film nobody in Hollywood wanted proved to be a great hit.

As Arthur Schlesinger Jr. said, “Historically, it was one of the earliest movies to express any kind of repugnance against Hitler and Nazism, and it did so, it seems to me, with sublime artistry. It may be in some ways Chaplin’s most memorable movie, and the part of the film that was most widely criticized at the time—that is, the concluding speech, might have seemed mawkish at the time, but in the context of the nuclear age, I think it has great resonance and great power.”

Despite the cavils of critics in 1940 and since, The Great Dictator has retained its hold on audiences, and remains a popular picture, perhaps because its subject is perennially relevant—the authoritarian mindset is always with us. While there are certainly more perfect films, there are very few as courageous. Chaplin was never more confident of his physical virtuosity—the scene of Hynkel dancing with the globe is immediately followed by the Jewish barber shaving a client to Brahms’ Hungarian Rhapsody. First he shows you the dictator’s megalomania, then the barber’s unassuming expertise, both characters defined by movement set to music.

As for theoretical pro-Communist leanings, The Great Dictator didn’t receive a showing in Russia until March of 1989, when Raisa Gorbachev hosted a screening. By that time, Charlie Chaplin had been in his grave for twelve years.

__________________________________

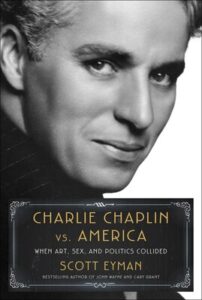

Excerpted from Charlie Chaplin vs. America: When Art, Sex, and Politics Collided by Scott Eyman. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Previous Article

Now is a Time to Speak:An Open Letter to the 92nd Street Y