A man.

Standing, watching: the beach, the sea. The sea is calm, flat; season indefinite, moment lingering.

The man stands on a boardwalk over the sand.

He wears dark clothes. His face distinct.

His eyes clear.

He does not move. He watches.

The sea, the beach, a few tidal pools, flat surfaces of water.

Between the man who watches and the sea, far off, all the way at the water’s edge, someone walking. Another man. Wearing dark clothes. From here his face is indistinct. He walks, going, coming, he goes, comes again, his path is rather long, never changing.

Somewhere on the beach, to the right of the one who watches, a movement of light: a pool empties, a spring, a stream, many-mouthed streams, feeding the abyss of salt.

To the left, a woman with closed eyes. Sitting.

The man who walks looks nowhere, looks at nothing, nothing but the sand in front of him. His pace is steady, unceasing, distant.

The triangle is completed by the woman with closed eyes. She is sitting against the wall that separates the beach from the town.

The man who watches is between this woman and the man who walks along the edge of the sea.

Because of the man who walks, constantly, with his slow, even stride, the triangle stretches long, reforms, but never breaks.

This man has the even steps of a prisoner.

Day dwindling.

The sea, the sky, fill the space. Far off, the sea, like the sky, already oxidized by the shadowy light.

Three, three in the shadowy light, a slow-shifting web.

The man is still walking, coming, going, before the sea, the sky, but the man who was watching has moved.

The even sliding of the triangle ceases.

He moves.

He begins to walk.

Someone walks, nearby.

The man who was watching passes between the woman with closed eyes and the other, far away, the one who goes, who comes, a prisoner. You hear the hammering of his steps on the boardwalk. His steps are uneven, hesitant.

The triangle comes undone, reforms. It comes apart. The man passes. You see him, you hear him.

You hear: his pace slacken. The man must be looking at the woman with closed eyes sitting before him.

Yes. The steps stop. He looks at her.

Only the man who walks along the sea continues his movement, his unending prisoner’s pace.

The woman is watched.

She sits with her legs stretched out. She is in the shade, huddled against the wall. Eyes closed.

Unaware of being seen. Not knowing she is being watched.

Facing the sea. Blank expression. Hands half-buried in the sand, still, like her body. Strength sapped, shifted toward absence. Stopped short. Not knowing. Unaware.

The steps resume.

Uneven, hesitant, they resume.

They stop again.

Again resume.

The man who was watching has gone by. His steps fade. He can be seen, he walks toward a sea wall between the woman and the one who walks along the shore. Past this sea wall, another town, and farther still, distant, another town, blue, begins to blink with electric lights. Then other towns, more, more of the same.

He comes to the sea wall. He does not pass it.

He stops. Sits.

He sits on the sand, facing the sea. He ceases to see any of it, the beach, the sea, the man who walks, the woman with closed eyes.

For one moment, no one watches, no one is seen: neither the mad prisoner who is still walking along the shore, nor the woman with closed eyes, nor the seated man.

For a moment, no one listens, no one hears.

And then there is a cry: the man who was watching closes his eyes, seized by a feeling that lifts him, lifts him up, lifts his face up to the sky, his face contorts, and he cries out.

A cry. Someone cried out over by the sea wall.

The cry uttered and heard throughout space, whether occupied or empty. It has torn the shadowy light, the stillness. The steps of the man who walks have not stopped, have not slowed, but she, she lifts her arm slightly, like a child, covers her eyes, stays like this a couple of seconds, and he, the prisoner, this motion, he has seen it: he has turned his head in the direction of the woman.

Her arm lowered now.

The story. It begins. Began before the walk along the edge of the sea, the cry, the gesture, the movement of the sea, the movement of the light.

But now it becomes visible. It is already tracing itself onto the sand, on the sea.

The man who was watching returns.

Again his steps are heard, he is seen returning from the direction of the sea wall. His pace is slow. His gaze distracted.

As he approaches the boardwalk, a rising noise, cries, cries of hunger. Seagulls. They are there, were there, all around the man who walks.

The steps of the man who was watching.

He passes before the woman. He comes within range of her. He stops. He looks at her.

We will call this man the traveler—if there is need—because of the slowness of his stride, the distractedness of his gaze.

She opens her eyes. She sees him, looks at him.

He comes closer to her. He stops. He has reached her.

He asks:

–What are you doing here, night is falling.

She replies, very clearly:

–I’m looking.

She gestures before her, the sea, the beach, the blue town, the white roofs beyond the beach, everything.

He turns: the man who walks along the shore has disappeared.

He takes another step, leans against the wall.

He is there, next to her.

The intensity of the light changes, is changing.

It grows white, changes, is changing. He says:

–The light is changing.

She turns slightly toward him, she speaks. Her voice is clear, so gentle and mild, nearly frightening.

–You heard someone cry out.

Her tone does not invite response. He responds:

–I heard.

She turns back to the sea.

–You arrived this morning.

–Yes.

The pattern of her thought is clear. She gestures around her, the space, she explains:

–This—this is S. Thala, all the way to the river.

She is silent.

The light changes again.

He raises his head, looks in the direction of her gesture: he sees that from the far end of S. Thala, toward the south, the man who walks is returning, making his way through the seagulls, he is returning.

His pace is even.

Like the changing of the light.

Accident.

Again the light: the light. Changes, then suddenly does not change anymore. Brightens, freezes, even, shining. The traveler says:

–The light.

She looks.

The man who walks has reached the point in his walk where he had stopped a moment earlier. He stops. He turns, he sees, he too looks, he waits, he looks again, he starts again, he comes.

He comes.

His footsteps cannot be heard at all.

He arrives. He stops opposite the one who leans against the wall, the traveler. His eyes are blue, piercing, transparent. The emptiness in his gaze is absolute. He speaks with a firm voice, gesturing around him, everywhere. He says:

–What’s happening here?

He adds:

–The light has frozen.

His tone expresses violent hope.

Light frozen, shining.

They look all around them at the flood of light, shining. The traveler speaks first:

–It will shift again.

–You think?

–I think so.

She is silent.

He approaches the traveler leaning against the wall. His eyes fix on him, blue, engulf him. The man gestures with his hand, points beyond the sea wall.

–You’re staying at the hotel over there?

–Yes. I arrived this morning.

She is silent, still watching the frozen light. He takes his eyes off the traveler, notices the stillness of the light.

–Something is bound to happen. This is impossible.

Silence: with the light, sound also has ceased, the sound of the sea.

His blue gaze comes back to focus upon the traveler:

–This isn’t the first time you have come to S. Thala.

The traveler tries to answer, several times he opens his mouth to respond.

–Well—you see—he stops.

His voice has no echo. The stillness in the air equals the stillness of the light.

He tries to answer.

They don’t expect a response.

Unable to respond, the traveler raises his hand and gestures at the space around him. Finally, he manages to come closer to an answer:

–Well—he stops—I remember, yes, I remember–

He stops.

Her luminous voice rises up to him with dazzling clarity, she asks:

–What?

An uncontrollable shudder, from within, overwhelming, leaves him breathless. He whispers:

–All of it. Everything.

He has answered:

the movement of the light resumes, the sounds of the sea resume, the blue gaze of the man who walks recedes.

The man who walks gestures at everything, the sea, the beach, the blue town, the white capital, he says:

–Here, this is S. Thala, until the river.

His movement stops. Then his movement resumes, he gestures again, but more precisely, it seems, at all of it, the sea, the beach, the blue town, the white town, towns beyond, others still: all the same. He adds:

–And after the river, that’s S. Thala as well.

He leaves.

She gets up. She follows him. Her first steps are unsteady, very slow. Then they even out.

She walks. She follows him.

They move away.

They skirt S. Thala, it seems; they do not enter its depths.

Dusk falls.

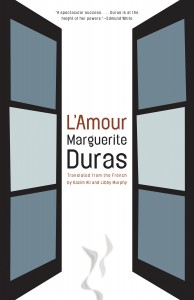

From L’AMOUR. Translated from the French by Kazim Ali & Libby Murphy. Used with the permission of Open Letter Books. Copyright © 1971 by Éditions Gallimard, Paris. Translation copyright © 2013 by Kazim Ali and Libby Murphy.