Kristen Radtke: How Do You Turn a Graphic Novel Into a Compelling Audiobook?

The Author of Seek You on Recreating the Intimacy of Images With Voice

In recent years I have grown to love audiobooks; I might love listening to an audiobook just as much—or sometimes even more—than reading a book on the page in front of me. I spend a great deal of time listening to them while I draw my own books, books that will mostly never become audiobooks themselves, because graphic novels usually aren’t something to be read out loud in the way prose novels are. If images are often the propeller of a story, how does one create an audio version without writing an entirely different narrated project? Film and TV often features audio descriptions for blind and visual impaired audiences, introducing an additional narrator, a disembodied voice who describes what’s happening in the scene between character’s dialogue. But an audiobook with a single narrator and no sound effects presents a different set of limitations.

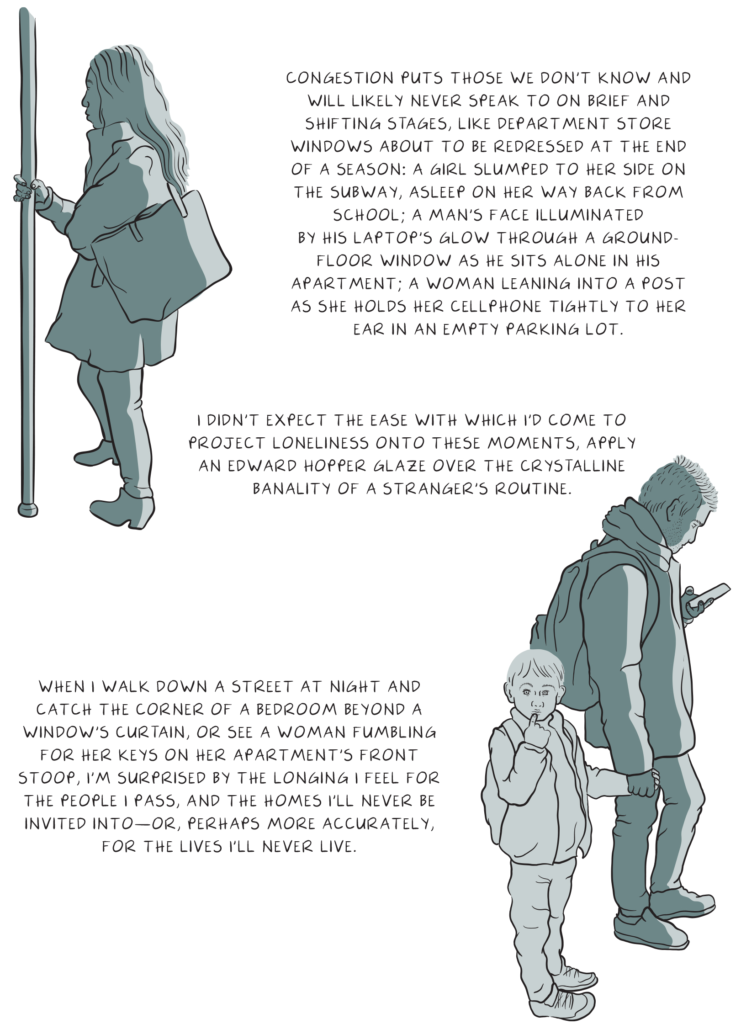

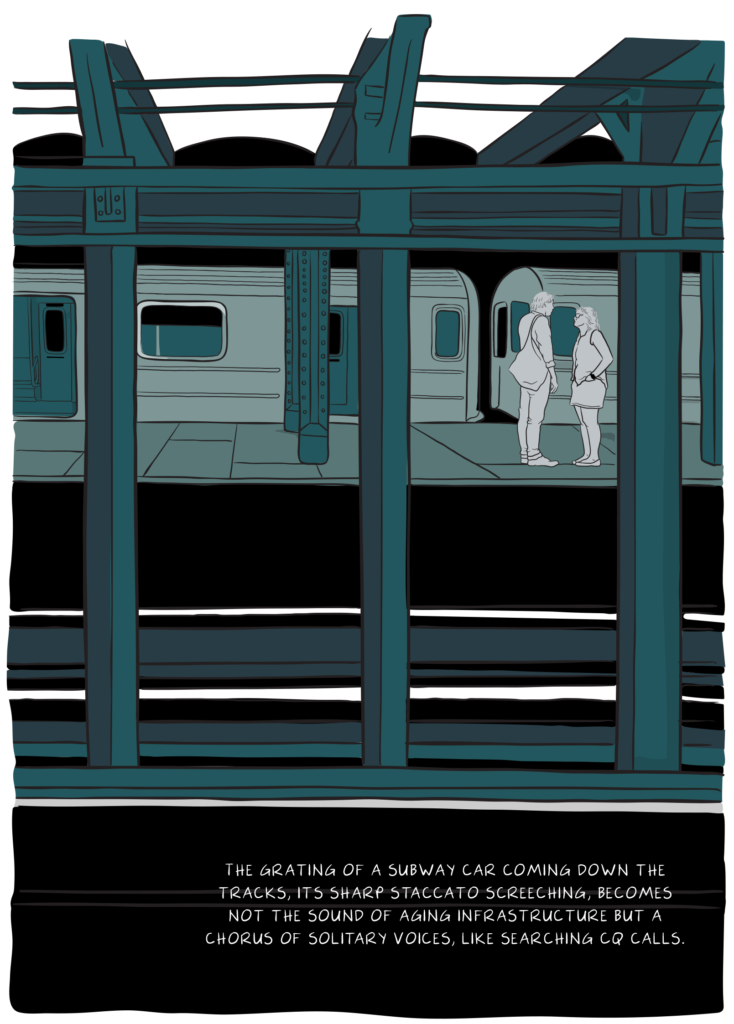

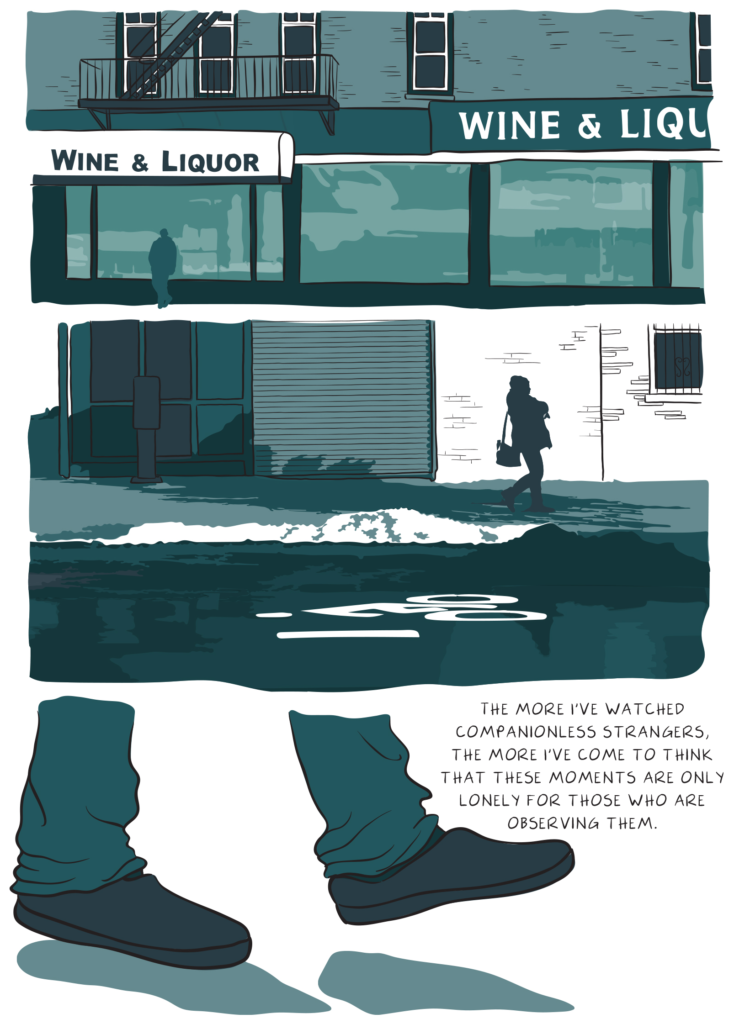

The most standard format for a graphic narrative is sequential art—a book constructed of panels, in which the action of one panel leads into action in the next. Seek You is the first graphic project I’ve completed that exists outside this structure. It began as a book of essays, and morphed over time into something like a book-length essay. It wasn’t built out of character and scene the way a comic might be. I can’t recall how I stumbled into the form I began drawing in, but somehow, Seek You was pulled out of the panels I was used to working in and into something more freeform, where the drawings took up whole pages and morphed into each other, with text winding through them. The images aren’t always a propeller for the story or the argument in the way they are in sequential arts; the images and text are often in conversation with each other, but the text remains the driver.

There was an opportunity, then, to translate this kind of book of drawings and text into audio form. Some things, of course are lost: I couldn’t recreate pages of wordless images with my voice, but the challenge offered an opportunity to think about how information that I depicted visually could be spoken. I have a deep affinity for labelling the parts of a drawing with arrows and asides; I love diagrams and drew many in the book, such as when I identified the parts of a machine that produced fake laughter during early sitcom tapings, or labeled each element of a cage in which scientists observed isolated monkeys. One thing I enjoy most about nonfiction comics is that I can communicate in words without using complete sentences; these diagrammatic drawings operate as a kind of footnote or side commentary.

When I recorded the audiobook, I rewrote some of these as sentences and read them aloud, but others were lost—they offered a secondary notation on the page, but I couldn’t justify them taking up space in a primary narration. This was a constant negotiation, just as deciding what was to be written and what was to be drawn on the page was a negotiation. The standard I’d set for myself with the book was that if I could draw it, I would draw it: I’d only write what I couldn’t say in images. Had Seek You been a plot-driven graphic novel, this would’ve eliminated its opportunity for audio adaptation, but because I was making most of my arguments in prose, the project became only about translating what existed in image, and deciding what I could live without.

I’d been warned by friends that recording one’s audiobook is grueling, and an exercise in humiliation over all the words you suddenly discover you’ve been mispronouncing your whole life. I agreed; it was horrifying to hear the sounds of my own mouth magnified in my ears while two patient producers listened in. But this is also the intimacy of audiobooks: an author is quite literally whispering into your ear for hours. Whenever I meet a writer for the first time whose voice I’ve already listened to, I come armed with the misapplied feeling that we already know each other.

There’s intimacy in drawing, too, in the enormous attention it takes to render a human form or face. I was disappointed to lose that in the audiobook, such as when I recorded the loneliest memories of some of my friends, which I’d lettered around their faces in the print book. The portraits to me felt imbued with the feeling of their stories, and I hated severing the two. But to speak their experiences out loud was also a closeness I couldn’t create on the page.

I don’t know what the experience of listening to this book will be like for readers, or how it will compare to those who page slowly through the drawings. There are so many ways to say something, and every artist must use the tools available to them to speak. If drawing is a form of speaking, then this process of translation reminded me that image is a language all its own. I only hope I captured the heart of it.

*

Excerpt from Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness. Courtesy of Pantheon Books. © Kristen Radtke

Kristen Radtke

Kristen Radtke is the author of the graphic nonfiction book Imagine Wanting Only This. The recipient of a 2019 Whiting Creative Nonfiction Grant, Radtke is the art director and deputy publisher of The Believer. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Marie Claire, The Atlantic, The Guardian, GQ, Vogue, and Oxford American, among many other publications. Seek You, out now, is published by Pantheon Books.