Kelly McMasters on Starting a Bookstore to Save Her Marriage

“And so, I kept pumping the bellows, trying to keep the fire between us burning.”

The first time I sliced open a box of books in my new bookshop, I breathed in deeply. The pulpy starch of the paper caught in the back of my throat, while the faint chemical sting of the new ink burned high in my nostrils. I imagined a world where this smell was a constant in my life and smiled to myself.

When you live in the countryside, “new book” smell is scarce. In rural Pennsylvania, used books abound in antique and thrift shops, library and church sales. Our house reeked of them; my bookshelves were full of old books soaked with the funk of other people’s sweat and smoke, speckled with grey mold, full of crumbs and marginalia.

New books are an expensive novelty; Amazon and e-readers are the closest you can get. In the city, I took for granted that in most places I lived I had a neighborhood bookstore, and I never had to walk more than a few blocks to get my fix.

At various times I’d been a regular at Housing Works, the Strand, McNally Jackson (when it was McNally Robinson), Book Culture (when it was Labyrinth), BookCourt (before it closed). I traveled to get to other favorites like 192 Books and Greenlight, but never more than one or two chapter-lengths on a subway train. Years out from living in the city, I hadn’t realized how much I missed that smell. I didn’t understand how much I’d taken bookshops for granted. And suddenly, now, I was standing in my own.

This shop—this was a fresh start, something we could plan and build together, with intention.

My younger son, almost a year old, shifted on the green chaise lounge in the corner. He was napping while I set up the store, a few days before opening. I’d kangarooed him in the baby carrier as I readied the room until he fell asleep, and then I laid him out to rest on the chaise, unhooking the carrier from my waist and shrugging my shoulders out without waking him. He lay there now, brow furrowed, lips pursing as he nursed from a phantom breast in his dream, chin jutting out in defiant pleasure. I calculated the length of his typical nap and held this against the work that still needed to be done, mentally building a list of things I would be able to do while holding him and things I needed to do while untethered.

As I calculated, the winter light filtered in softly through the old window panes. The shelves stood empty, waiting to be filled. Folded paper trees lined one table, waiting to be hung, an offering from R., homemade holiday decorations. Aside from the tall counter borrowed from the shop’s landlords, the furniture was mostly pulled from our barn: two display tables, a high stool behind the counter, the weird green velvet chaise we’d bought years ago from a friend in Williamsburg who’d lost her job as a fashion publicist and was selling some things to make rent. It astounded me that all we needed to make a bookshop was some furniture, some books, and a room in which to put them.

*

In the year before we opened the shop, I’d stopped wearing makeup or coloring my hair, allowed R. to cut it instead of going all the way to town to the hairdresser. I wore only clothes that had elastic at the waist and shirts that could be easily pulled down or lifted for nursing. I stopped reading.

I hadn’t made many friends yet and wasn’t certain how to go about fostering relationships out here. I tried to make plans with the wife of our real estate lawyer; she was a kindergarten teacher with two children similar ages to mine and she’d seemed friendly enough when we chatted at the farmer’s market on the weekends. I dialed her number and asked if she might want to get together for a coffee one day and I felt her voice tighten before she even spoke. “I take a twenty-minute walk with the double carriage every morning at seven o’clock sharp,” she snipped. “You’re welcome to join me any day of the week.” I thanked her and told her I’d get back to her, knowing I’d never be able to ready myself and my children early enough to make the forty-minute drive to her house just outside town—not that she really wanted me to, anyway.

I didn’t miss the city, but I missed who I’d been there on those bright streets, bag heavy with books slung over my shoulder, sure-footed and full of direction and purpose. My days had become a blur of softness; blending soft bananas and avocados into baby food, folding soft cotton burp towels over my shoulder, hands kneading soft toddler thighs or running through soft baby hair, my own body plump and unrecognizable without its intention and tautness.

Even my movements became a slow churn, repeated each day. Baby’s room, toddler’s room, kitchen. Bathroom, living room, kitchen. Baby’s room, toddler’s room, bathroom. Kitchen, living room, porch. I lived in three-hour spurts, marked by naps and feeding schedules. I took long walks down the driveway with my older son as he practiced walking. We threw rocks into the little stream, went mushroom hunting after rain, all with the baby strapped to my chest, nursing, sleeping, nursing, sleeping. That whole year felt like one very long day. We sang songs, held hands, held buttercups under one another’s chins. But still there was an unquantifiable ache that ran beneath even the sweetest moments.

It had only recently occurred to me that our ecosystem was only made up of three when there should have been four. Every so often, from our perches in the kitchen or snuggled on the couch, we would hear the painting studio’s screen door strain open and then slam, followed a few moments later by a clomp of boots coming up the steps of the porch. Our heads would swing to the front door, like dogs. Tense. Waiting.

I hadn’t grown up wanting children, hadn’t dreamed of being a mother or a wife or having a family. When my children were born, a love flamed inside me that I hadn’t known was possible. Still, I would never be a natural caretaker. An only child, I was not comfortable in the company of small children, but now they were my only companions. We became a secret constellation, moving together as one. I was not a cook, but I cooked. I was not a mother, but I mothered. I was not a wife, but I wifed. I felt like a broken compass needle, spinning and searching for purchase.

I could stand a failed business; I didn’t think I’d survive a failed marriage.

Meanwhile, R. had turned away from us. It was natural after children, some friends told me. But if I were honest, it wasn’t that he turned away, really. He just hadn’t turned toward us. In pregnancy and then with motherhood, my life was uprooted, unrecognizable. R.’s stayed mostly the same. He was frustrated that I had less time to spend on him, but he still spent most of his time painting, and his body remained his own, as did his clothes, his sleep schedule. When he worked, I watched the children. When I had to work, he reasoned that I should get a babysitter.

I made my own baby food, taught our toddler sign language, read up on preschool options and vaccinations. When I would talk about these things, or about my students, or about the way my writing was starting to feel like something I used to do, his eyes would find the clock or his feet would move restlessly under the table. Mostly, it felt like he was passing the time until he could get back to his easel. This wasn’t a new feeling, but I’d never needed his partnership the way I needed it now.

In the weeks before we opened the bookshop, I could feel R.’s interest spark. He paid attention during our conversations, stayed at the dinner table longer. He was not very interested in learning how to build an e-commerce site or keep accounting records, but he liked the idea of selling prints, of hosting art openings. He had no interest in building a gallery or showing anyone else’s work—just his. But he had the energy he’s always gotten right before a big opening, the energy of possibility, of hope.

Of course, I knew too well that the elation of opening night was always followed by a cliff dive of emotion. No matter the crowd or sales, it never measured up to his hopes, or what he thought his work deserved. These were simple equations; even my toddler grasped that what went up must come down. Still, I ignored that portion of the pattern, even though part of me must have known it would come; it had been so long since I’d seen that kind of fire in him, and I wanted to help sustain it.

It was clear to me through my midnight calculations and YouTube-trained business plan drafting that this venture would not make us much, if any, money. We wouldn’t be able to take salaries for at least three years, every dollar pouring back into the store. But, like Bill and Paul, and Jim and Laura, and so many of our friends in the country, we’d become masters of improvisation, juggling multiple side hustles that we would continue while we shared the shop hours, chose the books together, hung the prints together, maintained the website together. There would be sacrifices, but we would make them as a team.

At each step of our relationship, we’d seemed to get thrown off-course. We’d been in New York the day of the World Trade Center attacks and that morning had grafted us to one another. Early in our relationship, he’d had two heart attacks, one shortly before our wedding and another a few months after, just as we bought the farmhouse. We’d had to adjust our expectations and plans. We put off the honeymoon, the house renovations, travel. Then the kids came. The past ten years seemed to just happen to us. But this shop—this was a fresh start, something we could plan and build together, with intention.

Even though every atom in my body told me opening a shop would be an economic failure, I’d hoped it would save us. I could stand a failed business; I didn’t think I’d survive a failed marriage. And so, I kept pumping the bellows, trying to keep the fire between us burning.

__________________________________

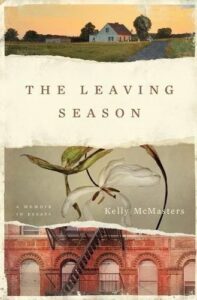

Excerpted from The Leaving Season: A Memoir in Essays by Kelly McMasters. Copyright © 2023. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Kelly McMasters

Kelly McMasters is the author of The Leaving Season and Welcome to Shirley, an Orion Book Award finalist, and coeditor of the anthologies Wanting: Women Writing About Desire and This Is the Place: Women Writing About Home, a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. Her essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, the Atlantic, the Washington Post Magazine, and the Paris Review Daily. A former bookshop owner, she teaches at Hofstra University and lives in New York.