Katy Simpson Smith on Writing a Southern Woman Louder Than Herself

“Fiction, as it turns out, allowed me to finally speak.”

My fingers quivered a little when I sat down to write a Southern woman protagonist. This would be a novel, I already knew, about insistence and rebellion and even violence, and I—born and gendered in Jackson, Mississippi—had successfully coated my own punk-rock qualities in sweetness. Could I let a fictional woman from my hometown be raw in a way I couldn’t? I was experimenting with one of the transformative promises of fiction: that the page can be even larger than a life. That it might even be able to save you from something.

I was raised in a house where Eudora Welty also happened to live briefly when she was young. I knew that writing could be a career, not just a hobby or a high-minded art, because we would see Miss Welty in the grocery store, and she had to be buying her bananas with some kind of income. We read Welty in high school, along with Margaret Walker and Richard Wright and of course Faulkner and, if our teachers were feeling racy, Tennessee Williams.

The literature that we read and valued—and that was valued by the whole nation, as evidenced by the Pulitzers and National Book Awards—was written by people with Southern accents, who had close relationships with their neighborhood grocery stores and interpreted history through the lens of race. That was me. I was in literature.

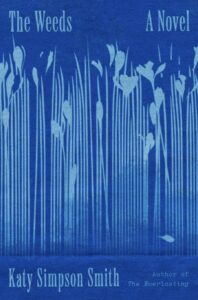

The protagonist of The Weeds, a novel that follows two female botanical assistants cataloging the plants growing in the Roman Colosseum, arrives in the Eternal City from what she considers a backwater: the American South. Her mother died when she was a teenager; she approaches life as an ongoing betrayal, an open wound. She has yet to experience anything that feels like salvation.

Could I let a fictional woman from my hometown be raw in a way I couldn’t?

As a child, I read voraciously. A well-meaning librarian even told me to slow down; if I kept reading so much, she said, I’d run out of books. This filled me with terror. Where would stories come from if I read the last one before I turned ten? She should have told me that stories are endless—not only will I never run out of books, that in fact I will be paralyzed when I look at the ratio of calendar days to my to-be-read stack, but that stories emerge out of thin air every day. That in fact I could write my own.

But did I believe I had something to say? The South is not a historically friendly place for women. We have been both reverenced and raped, but rarely respected. Through insidious codes of chivalry, white women were lured into a “protected” status of second-class citizens. In the nineteenth century, our shaky position on white men’s pedestals meant that not only did we have to conform to certain standards of behavior (chastity, virtue, Christian faith, exemplary motherhood) if we wanted to continue earning that protection, but we were convinced that our status rested on the fact that others were beneath us.

Paradoxically, we were only safe when we needed to be defended; we only needed to be defended when Black men and women were cast as threats, both to the social order and to our sexual purity. Through cowardice, a lack of real power, and, in some cases, pure malice, we became collaborators in racial terror. What were white women’s tools for survival, if not voting ballots or purchasing power or intellectual freedom?

Beauty, and sweetness, and balancing obedience to those above us with oppression for those beneath us. What were Black women’s tools for survival, without even the rights to their own bodies? Patience, quiet subversion, and, when possible, open revolt. But what does all this have to do with literature?

In my parents’ house with its abundant garden, no one forced me to wear dresses; no one treated me differently from my brother—except, of course, that he was the calm one and I was an emotional mess. I played with horses and Hot Wheels. I was told I could be anything. But still—still—I have moved through much of life tentatively. I have wanted badly to do the right thing; to bring joy to others; to not rock the boat. Writing, as a career, is inherently boat-rocking.

The protagonist of The Weeds had little of my childhood stability and, as an adult, has none of my self-policing tendencies. Her rawness is what I often felt on the inside. She rejects sweetness; she embraces fury instead. And why shouldn’t she? In addition to plant species, she catalogs the ways in which men—young and old, reckless and “responsible”—have visited violence upon her. Her Southernness doesn’t stop her from wanting to overturn all the boats in the sea. In this way, she is my fantasy.

I wrote in secret for a long time. First on my parents’ typewriter, later on their boxy early computers. It was a hobby, I told myself, like reading. But reading is also inherently disruptive. What was Madame Bovary doing with all those lovers in the buttoned-up nineteenth century? Why do we feel for Raskolnikov even after he murders an old woman with an axe? What is empathy but a shockingly strong solvent that can dissolve the barriers we humans so busily and vainly construct? In its ceaseless insistence on empathy, literature might even be deemed anti-social, if society is the artificial fences we build. This is perhaps why reading was seen as too dangerous for women for most of literate history.

So imagine a generation of women in the South, one of the most rigidly constructed societies of all, who chose not only to read but to write, and not only write but write imaginatively, broadly, and honestly. I think of Margaret Walker’s Jubilee, which upended the romance of Gone with the Wind and revealed plantation life as a source of horror rather than pageantry. I think of how Eudora Welty’s “Where Is the Voice Coming From?” unpacked the racist rationalizing of Byron de la Beckwith, Medgar Evers’ murderer.

I think of our current generation of Mississippi women: Jesmyn Ward telling the truths of Black girls and women living in a rural poverty that systematically targets Black men. Natasha Trethewey pulling the strands of history back to our original sins: the very conception of caste and color in early America. Angie Thomas writing about the concerns of Jackson teenagers in the voices of Jackson teenagers. None of these stories are safe or comfortable; no one asked these women for these stories. For most of our lives, no one really asks anything from women.

After my junior year, I dropped out of high school, tired of the culture, tired of Mississippi. I enrolled in a women’s college in Massachusetts. Like Welty—who studied in Wisconsin and New York—and Jesmyn Ward—who studied in California and Michigan—I felt the need to leave this state to gain perspective, though at the time I think I was leaving just to leave. And like Welty and Ward, I found the North to be hostile in new and different ways. Not enlightened at all, really, but with its racism buried deeper, its suspicion of strangers more overt. Like Welty and Ward, after a few years, I missed Mississippi intensely.

My unnamed protagonist takes a bit longer to feel this homesickness; she is, after all, in Rome, surrounded by bougainvillea and gelato. But there is a moment when she begins to take her home seriously as a place of possible beauty and not just a site for violence, for stifling gender norms. The ache she feels toward home—and the scorn her advisor heaps on her idea for a Mississippi-set research project—becomes the last trembling border between decorum and rage. As a novelist, as a Southern woman without much anger in her toolkit, I desperately, deliciously pushed her toward rage.

I moved back South for graduate school, this time to North Carolina to pursue a doctorate in history, writing a dissertation about the experiences of motherhood among white, Black, and Indian women in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century South. The more I understood how these long-dead women were using the one realm they were allowed some control over—motherhood—to craft a robust self-worth, and how this concerted and subversive force was coming from the South, the more I began taking my own fiction seriously.

Southern writers are tearing holes in the veils, recasting what’s considered speakable.

I took it so seriously, in fact, with the ghost of Welty grinning like the Devil on my shoulder, that I gave up my history career. Instead of applying for tenure-track university jobs, I applied for MFA programs in creative writing. Suddenly I felt like I was shouting all the things I had ever wanted to say—the stories I’d kept secret for years, that seemed inconsequential because they were written by me, a girl—and then someone wanted to publish them, and I didn’t die of shame and I wasn’t ostracized by my community.

Instead, I experienced what I think Welty must have experienced: a warm glow of acceptance, a little pride, and then a calm return to the work. Being a published writer didn’t, in fact, change my life. It just allowed the bud of my life to fully open. I stopped hiding.

In many ways, the South still prefers to keep certain things hidden. It’s still easier to be a woman if you’re sweet. Easier to be a man if you’re straight. Easier to be a human if you’re cisgender and white. But Southern writers are tearing holes in the veils, recasting what’s considered speakable.

And maybe my writing of this protagonist was a recasting of my own youth. I wish I had cut off my hair and yelled at people. I wish I had snappy comebacks to misogynist slights. I wish I’d known, in my twenties, that I was allowed to be fearless. What my protagonist learns is that courage doesn’t mean no one will hurt you; it means finding yourself whole in spite of the hurt. It means walking big in a world that considers you small. A sense of smallness is how silences are maintained. Fiction, as it turns out, allowed me to finally speak; it rescued me from a culture that took me years to learn how to cherish.

Mississippi women have long been doing what Mississippi writers have spent years imagining. This is our state’s complicated loop: our actions as a people are mythic and heroic and, yes, tragic, all of which lends itself to literature, and our literature, meanwhile, has its ear to the thrumming heart of the people and is never too far removed from the bodies and blood and struggle and fecundity.

This is the lesson I’ve taken from Eudora, from Margaret, from Jesmyn and Natasha. This is what the narratives of Mississippi have revealed. Etching small lives into literature—if it’s done with truth, justice, courage, and humility—can not only touch real people, but save them.

This essay was adapted from a speech given by the author upon accepting the Richard Wright Literary Excellence Award in Natchez, Mississippi.

__________________________________

The Weeds by Katy Simpson Smith is available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Katy Simpson Smith

Katy Simpson Smith was born and raised in Jackson, Mississippi. She is the author of the novels The Story of Land and Sea, a Vogue best book of the year; Free Men; and The Everlasting, a New York Times best historical fiction book of the year. She is also the author of We Have Raised All of You: Motherhood in the South, 1750–1835. Her writing has appeared in The Paris Review, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the Oxford American, Granta, and Literary Hub, among other publications. She received a PhD in history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars. She lives in New Orleans.