Kate Mulgrew on the Work of Waiting, in Acting and in Life

Reflections from the Star of Orange Is the New Black and Star Trek

A Thursday afternoon in the middle of January in a midwestern town is, at best, bleak. The sterile fields, covered with snow, stretch for miles in every direction. Occasionally, a farmer will leave a tractor or a thresher standing in the barnyard, as if in defiance of the laws of nature. These are oversights, however, because the people of Iowa understand that January is essentially a month of hibernation. In January, time stands still. The farmers see to their livestock, but spend most of their time indoors, checking the weather forecast, adjusting the thermostat. The farmers’ wives, otherwise so busy in their vegetable gardens, so prolific with their pies and breads, are forced to share their husbands’ solitude, which creates an atmosphere of tension. While the fields lie fallow, the men and women whose livelihoods depend on them resign themselves to the inevitable, and burrow in for a long winter of waiting.

Waiting, I thought, as I pressed my nose against the tall, frosted window in the dining room, is something I know a lot about. As an actress, I understood the nature of being forced to do nothing for extended periods of time, so I could sympathize with the farmers, but this sympathy was limited because I knew that the farmers, despite the long winter, could anticipate the arrival of spring. For actors, there is no springtime, there is only the telephone. There is only, ever, the job. Between commitments, an actor is rendered helpless by her own uselessness, so she learns very early in her career how to hibernate. She determines a routine from which she dares not deviate, lest anxiety rear its ugly head. Much like the farmers of Iowa, the actresses of New York learn to accept long periods of suspension, during which it is crucial to remain as composed and hidden as possible. They stock up on books, they listen to music, they take yoga classes. They retreat.

Their lovers, if they have them, may or may not be allowed to join them during these periods of imposed exile. It is of little consequence, the devotion of the lover, and can often be unduly annoying. An actress can do little with the lover’s ardent embrace because she is not, in fact, present. She is peering over the lover’s shoulder at the bedside table, upon which sits her mobile phone in its sleek protective jacket, black and silent as a spider. Should it ring in the middle of lovemaking, the actress knows she will disentangle herself from any erotic entwining faster than anyone would think humanly possible. The lover, dazed and disgruntled, will be left to wrangle with a snarl of empty sheets while the actress paces the entire length of her apartment, speaking in loud and often vibrant tones to the person at the other end of the phone. That magical being, capable of usurping a lover in less than a second is, of course, the agent.

This person, much less capable of devotion than the lover, is nonetheless more desirable to the actress than any lover could ever hope to be, and this is because the agent signifies the possible end to what has become an excruciating period of waiting. The agent, like an audible shot of prednisone, instantly restores the actress to a state of strength and vigor. In the time it takes to abandon her lover and retrieve her phone, leaping out of bed with the agility of an acrobat, she has already begun to reclaim her sense of purpose. As her voice fills the apartment with sounds of barely contained excitement, the lover wonders for the zillionth time what in hell he is doing in this woman’s bed, and why he always returns to it. But that is neither here nor there, because the lover’s period of agonized waiting does not concern the actress. What is important is that the actress’s period of waiting has come to an end.

As I climbed the stairs bearing a tray on which rested a glass of ice, a washcloth, and a can of Ensure, I realized that my father’s imminent death had filled me with a purpose not unlike the two-hour one-woman show I had been performing for more than a year. The process was surprisingly similar: both were physically as well as emotionally challenging, both called on certain unique skills, and both promised a closing. I could address my father’s dying with the same concentration I brought to playing a difficult role, a discipline acquired over many years of practice. Most important, the waiting was ameliorated by the intensity of my daily workload, self-imposed or otherwise. My siblings, while perhaps not understanding this on a conscious level, had nonetheless conspired to give me a principal role in this real-life drama.

Should the phone ring in the middle of lovemaking, the actress knows she will disentangle herself from any erotic entwining faster than anyone would think humanly possible.

I entered my father’s bedroom and, as I crossed to his bedside, emitted a small gasp of surprise when I realized that my sister Laura was sitting quietly in the armchair next to the tall, partially shuttered window on the far side of the room. I had thought I was alone and felt momentarily as if my thoughts had been caught red-handed. Laura had the ability to unsettle me.

She arrived nearly every afternoon around two and, after visiting Mother in the Good Living Room, made her way upstairs to our father’s bedroom. Once inside, she would move to his bedside and stand there for a few minutes, looking down at him. She didn’t touch him, nor did she make any attempt to care for him. She did not smooth the covers, she did not soothe his brow with a cool cloth, she did not bring ice chips to his lips. She stood and observed him. Then, satisfied, she withdrew to a corner of the room and situated herself in my mother’s faded yellow armchair. Often, she sat there for hours, disturbing no one, saying nothing.

Unlike my other siblings, who announced themselves with chronic politeness, Laura felt no such compulsion. She had come, she had taken a seat, she was holding vigil. She felt no need to explain her actions and was, if anything, slightly amused when I turned and said, “Jesus, Laura, you scared the shit out of me!”

“How ya doin’, Bate?” Laura asked, as softly as she could. After years of smoking and drinking, my sister’s voice had become rough and flat, devoid of nuance. Yet there was a gentleness in her manner when she asked me how I was doing, and the fact that she had addressed me as Bate indicated that she was in a forgiving mood. I cannot now remember why each of us had been reduced to the attachment of a nickname beginning with the letter B, an adjustment we found inexplicably hilarious. In stunningly short order, Tom had become Bom, I became Bate, Joe was Bo, and so on down the line, with variations on some names so as to avoid hurt feelings. Laura somehow lacked the desired rhythm as Bora, and so she was soon transformed into Bore or, in happier circumstances, Borley. Tess was Bess, a good, if lateral, move. Only the Smalls, Jenny and Sam, escaped the torturous alliteration and were nicknamed, respectively, Wren and Buck.

Curiously, I could never bring myself to call Laura “Borley” and, on the odd occasion when I attempted to do so, I felt awkward and affected. The others had no such difficulty, and I had grown accustomed to Joe and Tom referring to Laura almost exclusively as Borley. This, I knew, was meant with real affection, and yet I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Ours was a more formal relationship.

“I’m good, Laura. How long have you been sitting there?” I asked, scooping ice chips into a cotton handkerchief.

“Oh, I don’t know. Awhile, I guess,” my sister replied.

It was mid-afternoon, and the sky was gunmetal gray, but I could see my sister clearly from where I stood. Small and whippet-thin, her ash-blond hair curled close to her small head, she wore a pink polyester athletic jacket over black leggings, her narrow feet concealed in ankle-high brown boots. I felt her eyes on me as I attempted to moisten my father’s lips, and was suddenly acutely conscious of my mother’s apron, tied snugly around my waist.

“You’re good to come every day,” I continued, regretting the stiffness of the words as soon as they escaped my lips. Dialogue did not flow easily between Laura and me. I felt self-conscious in her presence, and always had. It was as if she could see something the others could not.

“That’s your explanation? You named her after a song because you liked the lyrics?”

“Well, he is my father, ya know,” she responded with a short, derisive chuckle.

“Did you have a chance to spend any time with him before he got sick?” I asked, looking at her across the room.

“Not really, Bate, because he just got sick, didn’t he?” Laura answered, again laughing drily. I interpreted this as a criticism, although of what I wasn’t entirely sure.

“I mean, did you spend any time with him before?”

Laura relaxed back into the armchair and smiled.

“Jeez, it’s too bad we can’t smoke in here,” she said. “I could really do with a smoke.”

“Go outside,” I suggested. “He’ll be here when you get back.”

“Nah, it’s all right. Stupid habit. I should quit,” my sister said, crossing her legs. “After all, look what it did to him.”

“He liked his drugs,” I quipped, thoughtlessly.

There was a brief silence in the room, during which I wondered if my sister had heard me or not.

“I didn’t know him very well, but I loved him. I sure respected the man, I can tell ya that. But we didn’t have a deep relationship, if that’s what you’re asking,” Laura explained, rising to her feet and approaching the base of the bed.

“Who did?” I asked, rhetorically.

“Well, Bo for sure had a friendship with Dad. And Bom, too. Dad loved the boys, always loved the boys,” she said, as if apprising me of this reality.

I lifted my father’s head gently and readjusted his pillow.

“He never really liked us girls,” Laura continued. “Bess, I guess, he loved her. Yeah, he loved Bess. But he wasn’t a daughter kinda guy, didn’t know how to relate to girls. Well, Jesus, Bate, you know what I’m talkin’ about.”

This was an ample mouthful for Laura, but her expression remained inscrutable. Each sentence was layered, and each had a secret meaning. The key to unlocking the secrets would be impossible to find.

Maybe she doesn’t need to understand everything she says, I thought, again busying myself with the bedclothes. Maybe it’s enough to come and sit with him in the stillness of the afternoon, maybe that’s as close as she wants to get.

My sister had moved to the other side of the bed, so that we were now facing each other. Her large blue-gray eyes were fixed on my father’s face, her fingertips resting gently on top of the duvet. I longed to say something to her, but I had no idea what that might be. Ours was a bond without resilience. We had not fought for a friendship, we had not suffered because of the lack of one. We had taken wildly divergent paths and, in so doing, we had lost each other.

“Why did you name her Laura?” I had asked my father, one night long ago, sitting out under the stars.

My father’s eyes softened, he held his cigarette to one side, and he began to sing. “‘Laura, that face in the misty light. Footsteps that you hear down the hall. The laugh that oats on a summer night . . .’ Hmm. Nice lyrics. Beautiful broad, Gene Tierney.”

“That’s your explanation? You named her after a song because you liked the lyrics?”

“Why not? Your sister was—what? Number four, number five? Your mother was at the hospital, in labor, and I was stationed at my post, waiting for the nurse to call. Killing time.”

“What post would that have been?” I demanded, rolling my eyes.

“My customary post at the tavern located two blocks from Mercy Hospital. The nurse would call the tavern, the bartender would hand me the phone, and bingo! Drinks on the house. Hell, I think that song may have been playing on the jukebox at precisely the moment the phone rang. Laura.”

It was a name in a dream. Undoubtedly, my father would have finished his drink, thrown down some money, and found his way to my mother’s bedside in the maternity ward. Equally unquestionably, my mother would have been asleep. A plump, imperturbable nurse would have directed my father to the nursery, where she would have pointed to a cot wherein lay a tiny figure, swathed in blankets and sporting a pink cotton cap.

“What are ya gonna name this one, T. J.?” the nurse would have inquired, smiling wryly.

My father, lost in the jukebox dream, would have looked at the cot and whispered, “Laura.”

Then, when the nurse had turned and walked away down the hall, my father would have pressed his nose to the glass. He would have stared for a moment at his fifth-born.

“Hiya, sugar,” he would have said. And then, buttoning his coat and flipping the collar up, he would have winked, and sauntered away. Laura’s enigmatic expression, as she stood across from me looking down at our father, had not changed, and it suddenly occurred to me that our father had very likely never shared this story with the daughter who had inspired it. In the intimate ambience of our father’s room, I considered telling my sister how she had come to be named Laura, but at the last minute decided against it.

__________________________________

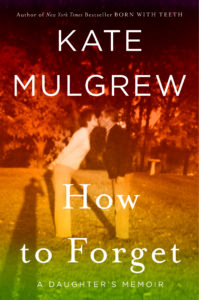

Excerpted from How to Forget: A Daughter’s Memoir. Used with permission of William Morrow. Copyright © 2019 by Kate Mulgrew.

Kate Mulgrew

Kate Mulgrew, a native of Dubuque, Iowa, is an actress and author with an extensive career on stage and screen. From her start as Mary Ryan, the lead role on the popular soap opera Ryan's Hope to the groundbreaking first female starship captain on Star Trek: Voyager to her acclaimed performance as Galina "Red" Reznikov on Netflix's smash hit Orange Is The New Black, Kate brings a formidable presence and deep passion to all her projects. Her 2016 book, Born With Teeth, allowed her to add "New York Times bestselling author" to her resume.