Karen Solt on Being Gay in the Navy

In Conversation with V.V. Ganeshananthan and Matt Gallagher on Fiction/Non/Fiction

In this Pride Month episode, Navy veteran and author Karen Solt joins co-host V.V. Ganeshananthan and guest co-host Matt Gallagher to talk about her experience of being gay while serving in the military. Solt, who retired as a senior chief petty officer in 2006 and served both before and during “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” talks about the Clinton-era policy that prohibited the harassment of gay service members while requiring that they stay closeted. Solt explains the impossible position gay military members were in before and during DADT, as they faced questioning from investigators, the threat of losing their jobs if found out, and being separated from their partners rather than being moved together as their straight counterparts often were. Solt reads from her book, Hiding for My Life: Being Gay in the Navy.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Matt Gallagher: You joined the military in 1984, and when you did that, you didn’t yet know you were gay. Could you say a little bit more about the circumstances under which you enlisted, and how your Navy career took off from there?

Karen Solt: Back in those days, gay visibility was minimal, especially in a small, conservative hometown like mine. I was a young kid who struggled quite a bit, and I didn’t really know why. I didn’t know it was because I’m gay, because I didn’t know that I was gay. I was barely graduating from high school when the Navy recruiter came and contacted a few of us who had no plans after high school, and I had no desire to go into the military. Six months later, he contacted me again. I was working at a gas station—really living the dream—and he said, “Why don’t we go down to Phoenix and talk to some people?” And where he took me was down to the MEPS station, which is where they take people to enlist. I was 18 and pretty naive, and I didn’t really have a sense of agency.

By the end of that day, I had raised my right hand with everybody else in that facility without really understanding what I was doing, but there I was. Today, young kids would probably know that they could have gotten out of it, but back in those days, I just thought, “Okay, I signed my name on the dotted line. I’m government property. And so, that’s really how I ended up in the Navy.”

V.V. Ganeshananthan I found the story, honestly, a little terrifying, because it seems to me like it could totally happen to kids today. I was thinking of Michael Moore filming, talking to people in Flint, and it’s a very different enlistment story than some others I have heard— someone thinks, “I’m going to change my life, or they have a parent or a family member who’s been in the military.” And they go in with a lot of decisiveness. I read this and was like, “Oh my goodness.”

Very early on in your service, you made a friend, Tammy, who was lesbian, and who told you that she was gay, which is an incredible moment in the book. She invites you over to her home and to meet her partner, and there, in the company of their friends who became your friends, you figure out that you are gay. The presence of gay communities within the Navy, like the one you form with Tammy and her partner, that’s a big part of your book—the sort of warmth and welcome of that community.

At one point you’re working in a Navy office in which half the women who have the same role as you do are gay, and so you write a lot about hiding information. I found myself also really interested in how information was shared, given the constraints that you were operating under, because you all managed to form these incredible communities around an identity that you were forbidden to talk about. Can you say a little bit about how that happened?

KS: Pretty quickly, I learned that there would be two aspects of myself. There would be the lesbian who was free with her gay underground community. Because that’s really what we were—this subculture within a larger culture that we really couldn’t exist in without getting punished or kicked out. Who we were was actually considered to be a criminal. So we learned how to protect each other. We learned how to speak a certain language. We changed pronouns. We watched out for each other when we were at work. We learned. I learned pretty quickly how to survive within the system.

After work, we had a great time, and it was this really loving, beautiful community. It was the first time that I really felt like I was comfortable in my own skin. It was like I found my family. I found a family within the military, and I also found my family outside of the military as well, within my gay community. It was really special.

VVG: In relation to that, I’m just thinking about that moment of disclosure, and it’s so intensely vulnerable because you are potentially disclosing your identity. You’re hoping you’re right, but if you’re wrong, potentially someone is going to report you. So fraught.

KS: Back in those days, we were being hunted by NCIS, which is not a TV show that’s accurate. We were truly being hunted by NCIS. They were trying to catch us, and so one of the things that NCIS would do back in those days was—we didn’t go to gay bars, I think I’ve been to gay bars two or three times in my life—they would plant people at gay bars. You might see somebody from the ship, and then you’re like, “Huh, is that person actually gay? Or is that person here because of NCIS?”

You really didn’t know who to trust and who not to trust. So for her to disclose her sexuality to me was a huge risk for her. She was a much bigger rebel than I was at the time. I was a huge rebel, but Tammy took that to a whole other level. I think from the moment that she met me, she knew I was gay, but I hadn’t figured it out yet, so we just became buds. I could have definitely been somebody that was a plant, and she could have been gone the very next day just by telling me that.

MG: Even by the standards of the military, having NCIS agents planted at gay bars seems like a tremendous waste of taxpayer money.

KS: Yeah, it was crazy. To me, it felt like this silent enemy was always hunting us. It became kind of embedded into my nervous system. I knew that NCIS was a threat. I knew that homophobic people were a threat. I knew that there were certain commanders or people in leadership that I had to be really careful of, but definitely NCIS before Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, they were the biggest threat.

MG: You end up staying in the Navy, both because you find your service fulfilling, but also for the camaraderie you share with your friends, such as Tammy. But she eventually becomes unbearably unhappy with her job, and she turns herself in as a way to get kicked out of the service. This effectively ends your friendship, because contacting her afterward would be too much of a risk for you. Women in relationships also struggle to stay together on different naval assignments because they don’t get assigned to the same duty stations the way straight couples are, under something called colocation. What other paths in your naval career over your 22 years of service were closed to you because of your orientation?

KS: I had a partner. We were together for a couple decades, and we met on active duty. About two and a half years into our relationship, she got transferred away with the promise that she would go somewhere for a year, and then we’d be reassigned together. That didn’t happen, and we were apart for three and a half years. So, I learned that three and a half years was challenging. Probably most of what I write about in the book encompasses that period.

We both ended up back in San Diego, which is a huge Navy community. She got transferred back, and I found orders back to San Diego. We were back in the same location, but neither one of us was willing to take assignments out of San Diego again, because we knew that if we got separated again, the chances of coming back together were really limited, especially when she made senior chief and I made senior chief. The billets that are available at that level are minimal.

Both of us sacrificed our careers at that point, and neither one of us made master chief. I believe that if we were a straight married couple, that both of us would have made master chief, because we could have taken challenging billets anywhere, and we would have stayed together. We made the decision that was best for us, and I wouldn’t change that, but it had a huge impact on my career.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Mikayla Vo.

*

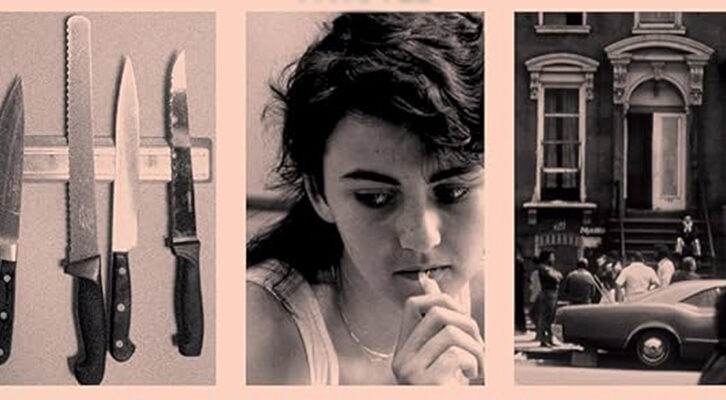

Hiding for My Life: Being Gay in the Navy

Others:

Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 7, Episode 30: “Tracie McMillan on the Myth of Colorblindness” • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 2, Episode 21: “Elliot Ackerman and Anuradha Bhagwati on the Role of the Military in American Politics” • The Lieutenant by Andrew Dubus • Roger & Me • A Former Marine Looks Back on Her Life in a Male-Dominated Military, by V.V. Ganeshananthan, The New York Times | April 17, 2024