Kamala Harris: Berkeley's Black and South Asian Communities Taught Me the Meaning of Family

"I could begin to imagine what my future might hold for me."

My mother was barely five foot one, but I felt like she was six foot two. She was smart and tough and fierce and protective. She was generous, loyal, and funny. She had only two goals in life: to raise her two daughters and to end breast cancer. She pushed us hard and with high expectations as she nurtured us. And all the while, she made Maya and me feel special, like we could do anything we wanted to if we put in the work.

My mother had been raised in a household where political activism and civic leadership came naturally. Her mother, my grandmother, Rajam Gopalan, had never attended high school, but she was a skilled community organizer. She would take in women who were being abused by their husbands, and then she’d call the husbands and tell them they’d better shape up or she would take care of them. She used to gather village women together, educating them about contraception. My grandfather P. V. Gopalan had been part of the movement to win India’s independence. Eventually, as a senior diplomat in the Indian government, he and my grandmother had spent time living in Zambia after it gained independence, helping to settle refugees. He used to joke that my grandmother’s activism would get him in trouble one day. But he knew that was never going to stop her. From them, my mother learned that it was service to others that gave life purpose and meaning. And from my mother, Maya and I learned the same.

My mother inherited my grandmother’s strength and courage. People who knew them knew not to mess with either. And from both of my grandparents, my mother developed a keen political consciousness. She was conscious of history, conscious of struggle, conscious of inequities. She was born with a sense of justice imprinted on her soul. My parents often brought me in a stroller with them to civil rights marches. I have young memories of a sea of legs moving about, of the energy and shouts and chants. Social justice was a central part of family discussions. My mother would laugh telling a story she loved about the time when I was fussing as a toddler. “What do you want?” she asked, trying to soothe me. “Fweedom!” I yelled back.

My mother surrounded herself with close friends who were really more like sisters. My godmother, a fellow Berkeley student whom I knew as “Aunt Mary,” was one of them. They met through the civil rights movement that was taking shape in the early 1960s and was being debated and defended from the streets of Oakland to the soapboxes in Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza. As black students spoke out against injustice, a group of passionate, keenly intelligent, politically engaged young men and women found one another—my mother and Aunt Mary among them.

They went to peaceful protests where they were attacked by police with hoses. They marched against the Vietnam War and for civil rights and voting rights. They went together to see Martin Luther King Jr. speak at Berkeley, and my mother had a chance to meet him. She told me that at one anti-war protest, the marchers were confronted by the Hell’s Angels. She told me that at another, she and her friends were forced to run for safety, with me in a stroller, after violence broke out against the protesters.

But my parents and their friends were more than just protesters. They were big thinkers, pushing big ideas, organizing their community. Aunt Mary, her brother (my “Uncle Freddy”), my mother and father, and about a dozen other students organized a study group to read the black writers that the university was ignoring. They met on Sundays at Aunt Mary and Uncle Freddy’s Harmon Street home, where they devoured Ralph Ellison, discussed Carter G. Woodson, debated W. E. B. Du Bois. They talked about apartheid, about African decolonization, about liberation movements in the developing world, and about the history of racism in America. But it wasn’t just talking. There was an urgency to their fight. They received prominent guests, too, including civil rights and intellectual leaders from LeRoi Jones to Fannie Lou Hamer.

My mother, grandparents, aunts, and uncle instilled us with pride in our South Asian roots. Our classical Indian names harked back to our heritage.

After Berkeley, Aunt Mary took a job teaching at San Francisco State University, where she continued to celebrate and elevate the black experience. SFSU had a student-run Experimental College, and in 1966, another of my mother’s dear friends, whom I knew as Uncle Aubrey, taught the college’s first-ever class in black studies. The campus was a proving ground for redefining the meaning and substance of higher education.

These were my mother’s people. In a country where she had no family, they were her family—and she was theirs. From almost the moment she arrived from India, she chose and was welcomed to and enveloped in the black community. It was the foundation of her new American life.

Along with Aunt Mary, Aunt Lenore was my mother’s closest confidante. I also cherish the memory of one of my mother’s mentors, Howard, a brilliant endocrinologist who had taken her under his wing. When I was a girl, he gave me a pearl necklace that he’d brought back from a trip to Japan. (Pearls have been one of my favorite forms of jewelry ever since!)

I was also very close to my mother’s brother, Balu, and her two sisters, Sarala and Chinni (whom I called Chitti, which means “younger mother”). They lived many thousands of miles away, and we rarely saw one another. Still, through many long-distance calls, our periodic trips to India, and letters and cards written back and forth, our sense of family—of closeness and comfort and trust—was able to penetrate the distance. It’s how I first really learned that you can have very close relationships with people, even if it’s not on a daily basis. We were always there for one another, regardless of what form that would take.

My mother, grandparents, aunts, and uncle instilled us with pride in our South Asian roots. Our classical Indian names harked back to our heritage, and we were raised with a strong awareness of and appreciation for Indian culture. All of my mother’s words of affection or frustration came out in her mother tongue—which seems fitting to me, since the purity of those emotions is what I associate with my mother most of all.

My mother understood very well that she was raising two black daughters. She knew that her adopted homeland would see Maya and me as black girls, and she was determined to make sure we would grow into confident, proud black women.

About a year after my parents separated, we moved into the top floor of a duplex on Bancroft Way, in a part of Berkeley known as the flatlands. It was a close-knit neighborhood of working families who were focused on doing a good job, paying the bills, and being there for one another. It was a community that was invested in its children, a place where people believed in the most basic tenet of the American Dream: that if you work hard and do right by the world, your kids will be better off than you were. We weren’t rich in financial terms, but the values we internalized provided a different kind of wealth.

My mom would get Maya and me ready every morning before heading to work at her research lab. Usually she’d mix up a cup of Carnation Instant Breakfast. We could choose chocolate, strawberry, or vanilla. On special occasions, we got Pop-Tarts. From her perspective, breakfast was not the time to fuss around.

She would kiss me goodbye and I would walk to the corner and get on the bus to Thousand Oaks Elementary School. I only learned later that we were part of a national experiment in desegregation, with working-class black children from the flatlands being bused in one direction and wealthier white children from the Berkeley hills bused in the other. At the time, all I knew was that the big yellow bus was the way I got to school.

Looking at the photo of my first-grade class reminds me of how wonderful it was to grow up in such a diverse environment. Because the students came from all over the area, we were a varied bunch; some grew up in public housing and others were the children of professors. I remember celebrating varied cultural holidays at school and learning to count to ten in several languages. I remember parents, including my mom, volunteering in the classroom to lead science and art projects with the kids. Mrs. Frances Wilson, my first-grade teacher, was deeply committed to her students. In fact, when I graduated from the University of California Hastings College of the Law, there was Mrs. Wilson sitting in the audience, cheering me on.

When Maya and I finished school, our mother would often still be at work, so we would head two houses down to the Sheltons’, whom my mother knew through Uncle Aubrey, and with whom we shared a long-standing relationship of love, care, and connection.

Regina Shelton, originally from Louisiana, was Aubrey’s aunt; she and her husband, Arthur, an Arkansas transplant, owned and ran a nursery school—first located in the basement of their own home, and later underneath our apartment. The Sheltons were devoted to getting the children in our neighborhood off to the best possible start in life. Their day care center was small but welcoming, with posters of leaders such as Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman on the wall. The first George Washington Maya and I learned about when we were young was George Washington Carver. We still laugh about the first time Maya heard a classroom teacher talk about President George Washington and she thought to herself proudly, “I know him! He’s the one who worked with peanuts!”

The Sheltons also ran an after-school program in their home, and that’s where Maya and I would spend our afternoons. We simply called it going to “the house.” There were always children running around at the house; lots of laughter and joyful play. Maya and I grew incredibly close to Mrs. Shelton’s daughter and foster children; we’d pretend that we were all going to marry the Jackson Five—Maya with Michael and me with Tito. (Love you, Tito!)

Mrs. Shelton would quickly become a second mother to Maya and me. Elegant and warm in equal measure, she brought traditional southern style to her grace and hospitality—not to mention to her pound cake and flaky biscuits, which I adored. She was also deeply thoughtful in both senses of the term—exceptionally smart and uncommonly generous.

I’ll never forget the time I made lemon bars to share. I had spent one afternoon making a lemon bar recipe that I’d found in one of my mother’s cookbooks. They had turned out beautifully, and I was excited to show them off. I put them on a plate, covered them with Saran wrap, and walked over to Mrs. Shelton’s house, where she was sitting at the kitchen table, sipping tea and laughing with her sister, Aunt Bea, and my mother. I proudly showed off my creation to them, and Mrs. Shelton took a big bite. It turned out I had used salt instead of sugar, but, not having tasted them myself, I didn’t know.

“Mmmm, honey,” Mrs. Shelton responded in her graceful southern accent, her lips slightly puckered from the taste. “That’s delicious . . . maybe a little too much salt . . . but really delicious.” I didn’t walk away thinking I was a failure. I walked away thinking I had done a great job, and just made one small mistake. It was little moments like those that helped me build a natural sense of confidence. I believed I was capable of anything.

Mrs. Shelton taught me so much. She was always reaching out to mothers who needed counseling or support or even just a hug, because that’s what you do. She took in more foster children than I can remember and adopted a girl named Sandy who would become my best friend. She always saw the potential in people. I loved that about her, too. She invested in neighborhood kids who had fallen through the cracks, and she did it with the expectation that these struggling boys and girls could be great. And yet she never talked about it or dwelled on it. To her, these deeds were not extraordinary; they were simply an extension of her values.

When I would come home from the Sheltons’, I’d usually find my mother reading or working on her notes or preparing to make us dinner. Breakfast aside, she loved to cook, and I loved to sit with her in the kitchen and watch and smell and eat. She had a giant Chinese-style cleaver that she chopped with, and a cupboard full of spices. I loved that okra could be soul food or Indian food, depending on what spices you chose; she would add dried shrimp and sausage to make it like gumbo, or fry it up with turmeric and mustard seeds.

My mother cooked like a scientist. She was always experimenting—an oyster beef stir-fry one night, potato latkes on another. Even my lunch became a lab for her creations: On the bus, my friends, with their bologna sandwiches and PB&Js, would ask excitedly, “Kamala, what you got?” I’d open the brown paper bag, which my mother always decorated with a smiley face or a doodle: “Cream cheese and olives on dark rye!” I’ll admit, not every experiment was successful—at least not for my grade school palate. But no matter what, it was different, and that made it special, just like my mother.

While she cooked, she would often put Aretha Franklin on the record player and I would dance and sing in the living room as though it were my stage. We listened to her version of “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” all the time, an anthem of black pride first performed by Nina Simone.

Most of our conversations took place in the kitchen. Cooking and eating were among the things our family most often did together.

When Maya and I were kids, our mother sometimes used to serve us what she called “smorgasbord.” She’d use a cookie cutter to make shapes in pieces of bread, then lay them out on a tray with mustard, mayonnaise, pickles, and fancy toothpicks. In between the bread slices, we’d put whatever was left in the refrigerator from the previous nights of cooking. It took me years to clue in to the fact that “smorgasbord” was really just “leftovers.” My mother had a way of making even the ordinary seem exciting.

There was a lot of laughter, too. My mother was very fond of a puppet show called “Punch and Judy,” where Judy would chase Punch around with a rolling pin. She would laugh so hard when she pretended to chase us around the kitchen with hers.

But it wasn’t all laughs, of course. Saturday was “chores day,” and each of us had our assignments. And my mother could be tough. She had little patience for self-indulgence. My sister and I rarely earned praise for behavior or achievements that were expected. “Why would I applaud you for something you were supposed to do?” she would admonish if I tried to fish for compliments. And if I came home to report the latest drama in search of a sympathetic ear, my mother would have none of it. Her first reaction would be “Well, what did you do?” In retrospect, I see that she was trying to teach me that I had power and agency. Fair enough, but it still drove me crazy.

The Bay Area was home to so many extraordinary black leaders and was bursting with black pride in some places.

But that toughness was always accompanied by unwavering love and loyalty and support. If Maya or I was having a bad day, or if the weather had been gray and depressing for too long, she would throw what she liked to call an “unbirthday party,” with unbirthday cake and unbirthday presents. Other times, she’d make some of our favorite things—chocolate chip pancakes or her “Special K” cereal cookies (“K” for Kamala). And often, she would get out the sewing machine and make clothes for us or for our Barbies. She even let Maya and me pick out the color of the family car, a Dodge Dart that she drove everywhere. We chose yellow—our favorite color at the time—and if she regretted having empowered us with the decision, she never let on. (On the plus side, it was always easy to find our car in a parking lot.)

Three times a week, I would go up the street to Mrs. Jones’s house. She was a classically trained pianist, but there weren’t many options in the field for a black woman, so she became a piano teacher. And she was strict and serious. Every time I looked over at the clock to see how much time was left in the lesson, she would rap my knuckles with a ruler. Other nights, I would go over to Aunt Mary’s house, and Uncle Sherman and I would play chess. He was a great player, and he loved to talk to me about the bigger implications of the game: the idea of being strategic, of having a plan, of thinking things through multiple steps ahead, of predicting your opponent’s actions and adjusting yours to outmaneuver them. Every once in a while, he would let me win.

On Sundays, our mother would send us off to the 23rd Avenue Church of God, piled with the other kids in the back of Mrs. Shelton’s station wagon. My earliest memories of the teachings of the Bible were of a loving God, a God who asked us to “speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves” and to “defend the rights of the poor and needy.” This is where I learned that “faith” is a verb; I believe we must live our faith and show faith in action.

Maya and I sang in the children’s choir, where my favorite hymn was “Fill My Cup, Lord.” I remember one Mother’s Day, we recited an ode to moms. Each of us posed as one of the letters in the word “mother.” I was cast as the letter T, and I stood there proudly, arms stretched out to both sides. “T is for the time she cares for me and loves me in every way.”

My favorite night of the week was Thursday. On Thursdays, you could always find us in an unassuming beige building at the corner of what was then Grove Street and Derby. Once a mortuary, the building I knew was bursting with life, home to a pioneering black cultural center: Rainbow Sign.

Rainbow Sign was a performance space, cinema, art gallery, dance studio, and more. It had a restaurant with a big kitchen, and somebody was always cooking up something delicious—smothered chicken, meatballs in gravy, candied yams, corn bread, peach cobbler. By day, you could take classes in dance and foreign languages, or workshops in theater and art. At night, there were screenings, lectures, and performances from some of the most prominent black thinkers and leaders of the day—musicians, painters, poets, writers, filmmakers, scholars, dancers, and politicians—men and women at the vanguard of American culture and critical thought.

Rainbow Sign was the brainchild of visionary concert promoter Mary Ann Pollar, who started the center with ten other black women in September 1971. Its name was inspired by a verse from the black spiritual “Mary Don’t You Weep”; the lyric “God gave Noah the rainbow sign; no more water, the fire next time . . .” was printed on the membership brochure. James Baldwin, of course, had memorably used this same verse for his book The Fire Next Time. Baldwin was a close friend of Pollar’s and a regular guest at the club.

My mother, Maya, and I went to Rainbow Sign often. Everyone in the neighborhood knew us as “Shyamala and the girls.” We were a unit. A team. And when we’d show up, we were always greeted with big smiles and warm hugs. Rainbow Sign had a communal orientation and an inclusive vibe. It was a place designed to spread knowledge, awareness, and power. Its informal motto was “For the love of people.” Families with children were especially welcome at Rainbow Sign—an approach that reflected both the values and the vision of the women at its helm.

Pollar once told a journalist, “Hidden under everything we do, the best entertainment we put on, there is always a message: Look about you. Think about this.” The center hosted a program specifically for kids through high school age, which included not only arts education but also a parallel version of the adult programming, in which young people could meet and interact directly with the center’s guest speakers and performers.

The Bay Area was home to so many extraordinary black leaders and was bursting with black pride in some places. People had migrated there from all over the country. This meant that kids like me who spent time at Rainbow Sign were exposed to dozens of extraordinary men and women who showed us what we could become. In 1971, Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm paid a visit while she was exploring a run for president. Talk about strength! “Unbought and Unbossed,” just as her campaign slogan promised. Alice Walker, who went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for The Color Purple, did a reading at Rainbow Sign. So did Maya Angelou, the first black female bestselling author, thanks to her autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Nina Simone performed at Rainbow Sign when I was seven years old. I would later learn that Warren Widener, Berkeley’s first black mayor, proclaimed March 31, 1972, Nina Simone Day to commemorate her two-day appearance.

I loved the electric atmosphere at Rainbow Sign—the laughter, the food, the energy. I loved the powerful orations from the stage and the witty, sometimes unruly audience banter. It was where I learned that artistic expression, ambition, and intelligence were cool. It was where I came to understand that there is no better way to feed someone’s brain than by bringing together food, poetry, politics, music, dance, and art.

It was also where I saw the logical extension of my mother’s daily lessons, where I could begin to imagine what my future might hold for me. My mother was raising us to believe that “It’s too hard!” was never an acceptable excuse; that being a good person meant standing for something larger than yourself; that success is measured in part by what you help others achieve and accomplish. She would tell us, “Fight systems in a way that causes them to be fairer, and don’t be limited by what has always been.” At Rainbow Sign, I’d see those values in action, those principles personified. It was a citizen’s upbringing, the only kind I knew, and one I assumed everyone else was experiencing, too.

__________________________________

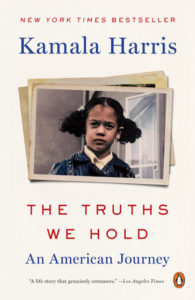

From The Truths We Hold by Kamala Harris. Used with the permission of Penguin Books.

Kamala Harris

Kamala Harris (kamalaharris.org) serves as a U.S. senator from California. Before becoming a senator, she worked in the Alameda County district attorney’s office, and was later elected district attorney of San Francisco and then Attorney General of California. The second African American woman and the first person of Indian descent ever elected to the U.S. Senate, and the third woman, first African American, and first person of Indian descent ever to run for vice president, she works hard to make sure all people have equal rights, especially kids. You can follow Kamala Harris on Facebook at Facebook.com/KamalaHarris or on Twitter @KamalaHarris.