Kalpana Raina on Translating Her Uncle Hari Krishna Kaul’s Stories of Kashmir

“There are no grand themes in Kaul’s work, but an exploration and ultimately an acceptance of human limitations.”

Growing up I was aware that my uncle, Hari Krishna Kaul, was a short story writer, a playwright, and somewhat of a celebrity in his hometown of Srinagar. That was enough for me and I never attempted to actually read anything he had written. I lived abroad and could not read Kashmiri, the language in which he wrote, although I spoke it quite fluently.

It was only in 2009, after Kaul’s passing and after I had spent more time in India, that I started to get a sense of his literary achievements. I heard him described, more than once, as one of the best modern short story writers in Kashmiri. I finally persuaded my father to read some of the stories out aloud to me. I knew Kashmiri well enough to immediately understand that Kaul had an impressive eye for detail, a superb command and ease with the language, and a biting wit that both mocked and conveyed empathy for his characters and their situations.

Through his work, he examined the minutest details of a very circumscribed Kashmiri Hindu way of life in the last few decades of the twentieth century in old-town Srinagar. This was the world he had grown up in and his ambivalent relationship with it is quite clear in the forewords to his four collections of short stories. There are no grand themes in Kaul’s work, but an exploration and ultimately an acceptance of human limitations. He used his personal experiences to explore universal themes of isolation, individual and collective alienation, and the shifting circumstances of a community that went on to experience a significant loss of homeland, culture, and ultimately language.

Never overtly dogmatic or biased, the simmering political and social conflicts that have dogged Kashmir lurk below the surface of these stories.Hari Krishna Kaul was born in 1934 in Srinagar. He spent his youth and most of his adulthood there, teaching at various academic institutions and leaving only in 1990 in the now well-documented exodus of Hindus from the city. Srinagar and the lives of its citizens are both the focus and the backdrop of Kaul’s works, particularly the short stories that span over forty years.

The first two collections, Pata Laraan Parbat (1972) and Haalas Chhu Rotul (1985) include some of his best known and popular works. The last two collections, Yeth Raazdanay (1996) and Zool Apaerim (2001) were published after Kaul left the Kashmir Valley. The selection of stories in the present Archipelago compilation represents a broad range of both popular and critically acclaimed works from these volumes. The minute observations of a beloved city, the detailed unfolding of ordinary lives lived there, uneasy accommodations between neighbors and communities that eventually end in departures and tenuous adjustments to a new life that was in no way desired; all is catalogued and dissected.

Never overtly dogmatic or biased, the simmering political and social conflicts that have dogged Kashmir lurk below the surface of these stories. Kaul’s characters, Hindu and Muslim, navigate a common landscape and language but warily, always conscious of the divisions that class and religious identity create.

His characters experience a slow dissolution of personhood as their circumstances, personal and professional, are peeled apart and reveal the void in their lives and the world they inhabit. Time and again, the bulwarks provided by family, jobs, social standing and religion crumble and the individual is left on their own. All this against a backdrop of a festering political and social instability in Kashmir which represents the here and now for these characters.

Through humor, compromise and conciliation, they negotiate their ordinary lives in a Kashmir rendered extraordinary by political compulsions. The world outside of Kashmir is alien, rarely named and always represented as “out there” in both a physical and an emotional sense. Mirroring Kaul’s own life, the numerous journeys back and forth between these two worlds ultimately end in exile.

In the first story of this collection, “Sunshine,” we witness this with the feisty Poshkuj, Kaul’s only significant female protagonist. Like the unnamed narrators of many of the later stories, Poshkuj’s unravelling of identity and the discomposure this leads to happen subtly. Through bursts of self-reflection peppered with comic descriptions and rendered in biting colloquial prose, we see her brash façade crumble as she struggles to find relevance in her new surroundings. Even on the first reading it becomes obvious why this remains one of Kaul’s most iconic stories.

The loss of community and the search for meaning that is hinted at in the earlier stories becomes a more direct quest later. Each story builds on this to culminate in “To Rage Or To Endure,” the last story in this collection. This is a work of astonishingly deft and spare language relying strongly on myth and metaphorical allusions. Here the narrator, unnamed again, stops mining his memories of Kashmir to make that final leap to an existence in exile where relationships and the past are extinguished in order to survive.

After leaving Kashmir in 1990, Kaul was acutely conscious that he had lost his Kashmiri-speaking audience for his television serials and plays. He took refuge in his stories, the stories that in the foreword to Pata Laraan Parbat he had called “the children that brought meaning to my meaningless life.” He produced two more volumes of stories in Kashmiri but also wrote extensively in Hindi in this period as he tried to carve out a new identity for himself and his writing. His only novel, Vyath Vyatha, was published in Hindi in 2005.

The stories drew me in and, inspired by the voice recordings, I succumbed to the temptation to translate.It was not initially my intent to translate any of the stories myself. My hope was to bring renewed attention to Kaul’s work through fresh contemporary translations and have a new and younger audience engage with them. To that end I enlisted the help of three young scholars and writers who collaborated extensively with me. We encountered significant roadblocks that I had not contemplated. Kaul’s own manuscripts and papers were not with his family.

Having left Kashmir practically overnight in difficult circumstances these “offspring” were abandoned in the old family home. The magazines in which Kaul published and his books were mostly out of print and any digital archives were inaccessible. The radio and television plays are still unavailable but one of my collaborators was able to locate all four collections of the short stories in the library of Kashmir University.

The physical state of these texts was less than ideal. They were in need of preservation. The ink of some pages had faded and entire sentences were sometimes erased, an undesired result of lithographic printing of the earlier volumes. But we managed to have them photocopied. These photocopies were circulated to a small group of Kaul’s contemporaries who, along with a handful of younger students and writers, helped us select stories from all four collections.

The three other translators on this project who could read Kashmiri in the Nastaliq script worked from these manuscripts. I had all the selected stories recorded in an attempt to engage members of my family and the extended diaspora who, like me, could not read the script Kaul wrote in. As we were going through our selections, I listened to these stories incessantly. They had a strong dramatic quality, and Kaul’s fluid use of the language made them perfect for the audio medium. This was not surprising given the author’s copious output of radio and television plays. The stories drew me in and, inspired by the voice recordings, I succumbed to the temptation to translate.

The journey toward an English-language translation was accomplished with multiple translators, all native Kashmiri speakers, but representing a diversity of gender, age, experiences, and religious identity. My knowledge of Kaul, his particular milieu, and the various backstories was enhanced by my collaborators’ familiarity with Kashmir, its literary history and landscape, and Kaul’s place in it.

For all four of us, this was our first experience reading and hearing Kaul and we collectively marveled at his command of the language, his wit and pungent humor, and the complexity of the characters he created. Though fully capable of reading the Nastaliq script, the other translators immersed themselves in the recorded stories as well. Like me, they used the recordings to help capture the orality of Kaul’s voice in their translations.

Despite our initial obstacles, the significant disruptions from recent political events in Kashmir and the global pandemic, this project found its way to completion. All these translations are ultimately the result of a collaborative and detailed engagement on the part of the four translators. We allowed each other to work on our separate drafts, but then, over two years of in-person and virtual meetings, interrogated initial assumptions and suggested alternatives that were sometimes accepted and sometimes discarded.

This was truly a collective undertaking. We listened, debated, and challenged each other’s understanding of the works. We took the process of translation a few levels deeper to bridge and create meaning for ourselves and for a culture and a language that still struggle to find their place in the world.

__________________________________

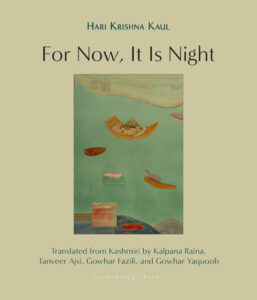

From For Now, It Is Night by Hari Krishna Kaul, translated by Kalpana Raina, Tanveer Ajsi, Gowhar Fazili, and Gowhar Yaquoob. Copyright © 2024. Available from Archipelago Books.