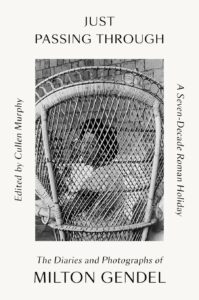

Milton Gendel’s long life—he died in 2018, two months shy of his 100th birthday—is hard to categorize. Gendel was born in New York City, the son of immigrants, but after age 30 lived primarily in Rome (and always thought of himself as a New Yorker who was “just passing through” the Eternal City). He was a critic (mainly for ArtNews) and photographer (though he was in his sixth decade before he exhibited his work) as well as a prolific diarist whose typewritten record totals some 10 million words.

Though Gendel himself was quiet, content to remain in the background, in Rome he was the quiet nucleus of a vibrant international set that included artists, writers, and actors; journalists and industrialists; glittering denizens of high society; and a multicultural assortment of aristocrats and royalty, some of them rather faded and others very much still in the public eye.

He created, as his daughter, Anna Gendel Mathias, once wrote, “his own cultural microclimate.” In his diaries, Gendel was discerning, trenchant, and funny; in his photographs, observant and yet strikingly unobtrusive. Taken together, Gendel’s words and pictures provide a window on a mid-20th-century world that seems to come alive once more.

I was a friend of Gendel’s and have collected selections from the diaries and photographs into a new book Just Passing Through—A Seven-Decade Roman Holiday.

In the excerpts presented here, Gendel describes a cabaret evening with Josephine Baker; an improbable moment in the life of Gore Vidal; the equally improbable path to marriage of the wealthy collector Mimi Pecci-Blunt; some reflections on her childhood offered by the biographer and historian Iris Origo; and the experience of attending church at Windsor with Princess Margaret.

*

Rome. Saturday, September 20, 1969

Met Josephine and Gosina in the bar of Piazza della Pigna and we drove to Via Veneto. At the Sistina Theater, a very mixed crowd—no familiar faces except that of Anna Magnani. Theatrical, TV, movie people, it seemed. And all ages. Years ago in Rome, only the old and the middle- aged had money for tickets, and there were very few young to be seen. Now it graded from sixteen up. Lots of modern gear. Girls who seemed to have forgotten their underclothes. Youths with long hair and velvet pants—purple and black and gold—with flapping bottoms. Lacey shirts. One youth in silver lamé, sort of chain mail.

A one-night stand of Josephine Baker, whom I had never seen. Expected an evening of nostalgia—“J’ai deux amours” and “C’est lui.” The banana queen of the Folies Bergère of 1925. First half of program unendurable. No Josephine Baker. Just mediocre bands and guitarists and comics.

Josephine Baker had the entire second half of the program to herself. A magnificent, flawless performer, from her first appearance on the stage in a voluminous dress with white feather collar, arms aloft, and a great open-faced toothy grin. A charge ran through the theater. Nostalgia was not the note; she is up-to-date in sound, rhythm, and words. Teasing about her age. “N’ayez pas peur” [Don’t be afraid], she said, making a move to unbutton. She is sixty-three. Then suddenly she took the whorehouse-madame’s coat off, and underneath she was in black slacks with glittering bell-bottoms. Very trim & lithe. Dancing, singing, walking into the audience trailing her wire. Entirely American, with seductive, fluent French with a heavy accent.

Rome. Thursday, December 17, 1970

Hugh Honour and John Fleming came to lunch at the Isola. Fleming, a former lawyer from Berwick, is white-haired and purse-mouthed. Honour is the younger mate, the odd-looking one, who does most of the talking. They are handling no less than six series for Penguin.

John asked me whether I knew Gore Vidal. “Well, he and his ‘secretary’ (you could hear the quotation marks as he underscored Howard’s role, with pleasure) were going around to see Vernon Bartlett’s house near us, with a view to buying it. Vernon and his wife invited them to lunch and were horrified to see them lugging a large, heavy suitcase when they got out of the car. Vernon said, My God, they have come to spend the night. They must have misunderstood. But Vidal explained when they got to the doorstep. His dog had stamped off the balcony at the Excelsior, in Florence, where he had been staying, and had killed itself. They had the body in the suitcase and wanted to know whether they could bury it somewhere in one of the fields.”

Rome. Saturday, February 20, 1971

Mimì and I dined off a card table in the salone, as usual. She said she had been working very hard at her papers—meaning that she had been putting her diaries and old correspondence in order. I urged her to start writing, and she said, Well, for one thing, it was just writing for posterity, as she would never publish now. Because she was just plain afraid of what her old friends would do to her.

The timid lioness.

Later, she was very amusing, telling again the story of her seventeen attempts at matrimony. “You know that Cecil was the eighteenth, and I almost lost him too before I finally got him. But the other seventeen—it’s a long story. To tell the truth, three of them asked me to marry them and I refused. Of these, one was a fat Bavarian who had cooled off anyway after looking in the bank and seeing that I had no money (che io non avevo denari); he went back to Germany—he had been in the embassy here—and married Big Bertha—yes, it was Krupp. Another was a grandee of Spain who was very much encouraged by my aunt in Madrid. I was all over Europe, looking for a husband. Switzerland, France, Spain, even Poland and Russia—but I’ll tell you about that later.

“I was only eighteen, and this Duca di Medinaceli asked me to marry him, but said that he had to explain something to me. He had a lover with whom he had lived for years, and he intended to keep her after we were married. At eighteen I was very proud—who knows if this had happened when I was twenty, I’d have known better—but I drew myself up and said, E mai, a poi mai [Never, and then never again]. My aunt was furious and in fact wouldn’t speak to me for years until she finally wrote—after I married Cecil—and invited me to Madrid again. I wrote her back saying, Grazie tante ma ora non ho più bisogno di te [Thanks a lot, but I don’t need you anymore].

“Well, then there was the trip to Poland. You see I had met this Princess Radziwill, who took a fancy to me and decided that I should marry a cousin of hers. So she invited me to their estate in Poland for the shooting. Yes, I shot, but not very well, and when I got there, I found that the cousin had a big beard and was not very thrilling. I don’t think he liked me very much, either, but the one who did like me was the son, and we came to an understanding during the visit. To cover my poor shooting he would help me out, and when I shot a wolf, the poor beast turned out to have four holes in it instead of one. I still have the head—at Marlia—you know, where you go upstairs to Dino’s rooms.

“But the mother was furbissima [very clever]. She did not want this marriage, because I had no dowry, so she came hastily to Rome and she told my mother she had something terrible but important to communicate to her. E quella furba ha raccontato a mia madre che suo figlio era sifilitico. Figurati! E mia madre, grata, con le lacrime agli occhi viene a dirmi che buon’anima che persona generosa—quella che era pronta a dire che il figlio era ammalato. [And that wily woman told my mother that her son had syphilis. Can you imagine! And my grateful mother, her eyes full of tears, told me what a good, generous person she was to admit her son was sick.]

“Oh, and then there was a very important match—but I had nothing to do with it—it was arranged by the Vatican. My great-uncle, Leo XIII, had started trattative [negotiations] for me to be given to the Duke of Norfolk . . . but nothing came of that.

“All the others I wanted to marry—fourteen of them, and I was always turned down in the end for lack of money. When finally I wrote to Papa [about Cecil], he couldn’t take my letter seriously. He put it away in a drawer until Miss Kemp—you remember—came fresh from Paris and assured him that it was true that finally I was engaged to be married. Then he took the letter out of the drawer and wrote to me. But I almost lost Cecil, too. His mother really wanted him to marry a French girl. She herself en secondes noces [on second wedding] was married to the Duc de Montmorency. She sent Cecil away to Nice to forget me.

“But I promised a hundred francs to San Antonio if I would get back what I lost, and soon I was invited to dinner by a woman who took an interest in me and had a young man for me to meet. And by chance Cecil had come back from Nice that day, so she asked him, too, and I had them on either side. Ma io non ho mai avuto peli sulla lingua [But I never minced words]. So I said to Cecil, Listen, your mother doesn’t want you to marry me. All right. But we can still be friends, can’t we? This stung him, and he said he could marry anyone he pleased, and the very next day he went out and bought me an engagement ring at Cartier’s. To this day I couldn’t tell you whether I said what I did out of furbizia [cunning] or because it was just an impulse. So we got married—my eighteenth prospect.”

Rome. Wednesday, May 30, 1973

Went to the Dunns’ and enjoyed myself thoroughly. I had a long conversation with Iris Origo, whom I haven’t seen in a very long time. Anna she had seen more recently, when Anna was spending the night with her granddaughter. They had come in in their nightgowns and sat on her bed.

“Oh, I liked the bedtime scene,” I said. She agreed and went on to praise Anna for her mind and her looks.

We had a rattling conversation, which included some nostalgic bits. I remembered the ball she gave for Benedetta, the romantic night with the blue-velvet sky and the cypresses. Palewski that evening said to her, she remembered, “Pour une femme qui dit qu’elle n’est pas mondaine ce n’est pas mal du tout” [Not bad at all for a woman who says she’s not a socialite]. She also remembered the ball as exceptional. And did I remember going with her to the Pincio to look for a site for the Byron statue? We couldn’t have chosen very well—under those tall pine trees it looked so miserable and dwarfed. We as the site committee might have put it among flowers, where it would have had a chance to look imposing, instead of overshadowed by those umbrella pines. I made a joke about training ivy over it.

She spoke about her shyness, how she always felt out of things when she was a girl, especially as she had to change among three different cultures, American, Italian, and English. Bernard Berenson dismayed her once, when she was seventeen, and he hurled a challenging question at her across his salotto, which was full of people. She mustered her courage and answered—something about what she wanted out of life. That’s what I mean, he said with disdain, addressing the others—that is conventional thinking. She spoke about his diaries and his self-dissatisfaction. I said that it was a pity he had been born too soon; he was a generation or two out of line. Nowadays there would be very little conflict over his commercial operations and his scholarship. He didn’t have enough balance to see that he had gotten out of life the most that he was capable of. He was a worldling with dreams of monastic cloistered scholarship.

London. Sunday, November 9, 1980

PM asked tentatively if I wanted to come to church—at St. George’s Chapel. “I don’t know . . . if you’re bored, the architecture and the details are worth studying, and sometimes the music is good.” I said I’d go. Another aspect of tourism.

PM and Anna dressed for church in the drawing room, watching the royal family laying a wreath at the Cenotaph. Lutyens, the polymathic imperial and country-house architect had done the design after WWI. It was meant to have smoke or an eternal flame spurting from the top. “Le phallus de l’état en jouissance” [the phallus of the state in ecstasy], as that clunk Marcellin would put it. We were all soberly dressed, in front of the TV set and on the screen. Picking out people we knew. PM of course knew the most. The great bulk of Christopher Soames.

The three of us, attended by Wellbeloved and Geoffrey in their semi-military bum-freezer livery (medals on chest), got into the little blue car and were driven to Windsor by the detective. The usual small crowd of tourists aimed cameras at PM. The governor of the castle, a military bigwig, was there to shake hands. And then the priest in charge of the chapel. A worldly fellow with an easy phrase and convinced handshake. He escorted PM to the upper row of choir stalls. She indicated that Anna and I should go in first.

Hymns and kneelings and sittings and the service under splendid fan vaults, sitting in the stalls of the Knights of the Garter. Their arms surmount the Gothic pinnacles of the stalls. Headdresses in cloth, one with a pair of arms extended, another with a turban, a helmet, and so on. In the flat apse a great stained glass window celebrating Prince Albert. Gilbert Scott.

Wonderful choir. A Schubert number toward the end of the service sounded like an opera aria, carried on a high soprano boy’s voice. It made one feel like getting up and waltzing. Princess Margaret met my eye and we had to restrain ourselves from laughing.

At communion time, the entire congregation, except for me and an old woman opposite, who also had not been kneeling, went to the altar rail. Two priests distributed wafers and wine. I noticed that an elderly priest with white hair carefully wiped the chalice after each sip of wine. The other, who was much younger, did not. I thought that he must be closer to the generation of communal joints passed from mouth to mouth—along with hepatitis. PM and Anna went up and communed.

At the end of the service, the priest in charge escorted PM back to her car. Handshakes and goodbyes. Laughing in the car over the lace-collared and scarlet-surpliced choirboy who had taken off in such a spectacular way.

Queen Elizabeth [the Queen Mother] was back from London. PM was giving her an account of my reactions to the Remembrance Day ceremonies at the Albert Hall as seen on TV. I gathered that PM had been carrying on a long campaign against the form of this ceremony, as she had said, “There’s nothing to be done with the Queen. I don’t know if she loves it, but she doesn’t see anything wrong in that mixture of the religious and all those numbers.” And I thought, the Queen has the common touch and knows what she’s doing. Queen Elizabeth had a patient look on her face as she listened to PM. “Milton agrees that a simple mass prayer would do instead of that procession with the bishop. After all, there is the Cenotaph the next day, when it is appropriate.”

She was interrupted by the arrival of Bryan Forbes, who came as if bounding in, with his wife Nanette Newman and his daughter Emma, a pretty sixteen-year-old who wants to be a ballerina.

Bryan talked all the way through lunch almost nonstop. Reminiscences, anecdotes, appeals to Nanette to confirm what he was saying. A tireless routine. Amiable enough and aiming to please. But it reminded me of the Peppers at their most striving, when they batted the ball back and forth and the ball was always some triumph of the Peppers or their children or, it must be said, their friends. Smearing success magic over everything.

Most of his anecdotes were of course about the theater, with some minor asides for Nanette’s books. “I don’t know how she manages to do everything, including writing books.” (I do—the books are children’s books and rather simpleminded.) His best was about Peter O’Toole in Macbeth and how he had decided to drench everything in stage blood, including his leading lady. (That Macbeth went down in theatrical history as the worst ever put on.)

Queen Elizabeth was radiating her melting charm in all directions, turning to me occasionally after Bryan had had the floor nonstop for a little too long and putting in a comment or a question. Somehow the war and the Germans came up. It was in connection with the Dutch paintings that had not been sent from Buckingham Palace and Windsor to the salt mines in Wales. She had them with her in the air raid shelter and got to know them intimately. This I suppose in connection with her polite interest in our visit yesterday to Windsor—and there she told how George VI had found Gainsborough’s letters on the royal portraits and rehung them according to his plan. Anyway, her conclusion concerning the war and its threats was to raise her glass of wine and then lower it below the level of the table as she ducked down playfully, saying “Down with the Germans!” Princess Margaret looked amazed and disapproving. “Mummy! Really, you know that’s wrong. I’ve always taught my children not to say things like that. It should be ‘Down with the Nazis.’” Queen Elizabeth looked charmingly devilish, lowered her glass again below the table, and said, “Down with the Germans.”

If things didn’t work out for Anna at Romana’s—Romana was sometimes odd, she was so scatty in Scotland you know—said PM, she must come to Kensington Palace. No, it wouldn’t be any trouble. She could use it like a hotel. Like you, said PM roguishly.

_______________________________

From Just Passing Through—A Seven-Decade Roman Holiday: The Diaries and Photographs of Milton Gendel. Edited by Cullen Murphy. Used with permission of the publisher, FSG.