Julie Schumacher on Thirty Years of Correspondence With Her Late Friend, Melissa Bank

"If I were writing to her now, which I suppose I am, I would tell her that I will remember her."

On the first anniversary of her death I am thinking, as I often do, of Melissa Bank, author of The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing and The Wonder Spot. She and I met in graduate school in 1985, while pursuing MFAs in fiction. When we weren’t struggling over our writing, we read and critiqued each other’s work: Why wasn’t it smarter/funnier/lovelier/subtler/clearer? Would anyone other than our classmates ever read it? What would we do when we finished our degrees?

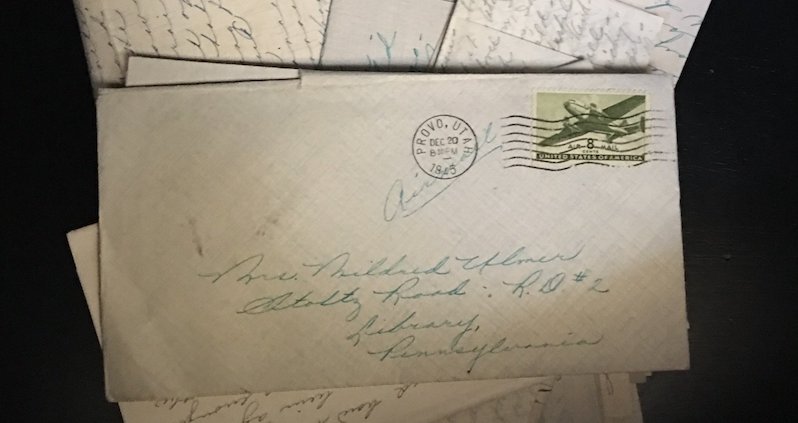

Here’s what we did: I moved to Minnesota with my spouse and taught part-time and had two kids; Melissa moved by herself to New York and worked full-time and got a dog. And because we were both still struggling to write, we kept in touch and sent letters. When Melissa died last summer, I opened the drawer in my desk where I had stored her correspondence, and I lined up thirty years’ worth of her letters, chronologically, on the floor.

Only a few of the letters were typed. The rest were handwritten, on greenish notebook paper with a torn row of fringe going down the left side. Melissa’s penmanship—a mix of printing and cursive—bristled with dashes and parentheses; it was legible but not neat, an immediately recognizable scrawl. We rarely emailed, our unspoken understanding being that the phone and computer were for logistics—for arranging a time to meet at the airport or the train. Our letters, on the other hand, were for conversation. Melissa’s fringed pages meandered companionably from subject to subject and seemed to overflow with her thoughts. By the way, she wrote in 2013, I just looked up biweekly in the dictionary and do you know it means every other week or twice weekly?

Writing and receiving letters, I think, helped sustain us.I loved those letters. One of the best things about our decades-long correspondence: it was leisurely and incremental, enriched by delay. Typically, a month or more elapsed before one of us answered the other. We wrote back when the epistolary impulse struck.

Though we often wrote about our efforts to create, our letters were creations unto themselves. Melissa doodled in the margins of her handwritten pages (Sorry, this page got sweaty), and we sometimes made and sent cards. I wish we could just spend all of our time making cards, eating candy & going to the movies, she wrote. (And, on the back of one of her envelopes, next to a return-address sticker bearing her name, she drew an arrow: Some charity gave me a page of these, hoping I’d donate. I didn’t.)

Our plan was to write to each other forever. So glad to hear you’re an Old Person, she wrote, when we were in our early forties, as I’m an Old Person too. We loved the anachronism of letter-writing. In 2008, Melissa promised that, if I visited her in New York, we could do anything you want—or nothing—just sit around & eat prunes & talk about how the internet is destroying the hearts & minds of today’s young people. And, eleven years later: I loved your letter, by the way; I love all your letters. I love that we’ll be writing them until the end of our days, growing crankier about the newfangled every year.

For half of her life—Melissa died at 61—we kept up a correspondence. Though we visited when we could (she once flew to Minnesota in the company of a large black dog named Maybelline), our friendship existed, primarily, on the page. Here on my floor was the postcard she made, with a 3-D watercolor image of one of my books. Here was the letter that included news of her mother’s death, here the drawing of a drawer full of eyeballs, and here the description of Melissa’s battle with depression (corrosive self-hatred, utter despair). And here, always, was our ongoing dialogue about books. He’s such a dick, Melissa wrote, about a novelist whose work we were both reading; what business does he have writing like a god? In another letter, she asked, Did you ever read The Magic Mountain & if so does ANYTHING happen? I just put it down after 200 pages—I began to feel that if I didn’t, I’d be on my way to a sanitarium myself. Pls let me know if I should pick it up again or not.

Over time, we both published and were more successful than we had hoped we might be. Melissa’s Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing was an international best-seller. But after a cancer diagnosis and a bicycle accident in Manhattan, she struggled to put words on the page. (I can get anxious about writing a to-do list for the cleaning person, she wrote).

Writing and receiving letters, I think, helped sustain us. I’ve been thinking about you so much—not worrying exactly but very conscious of you, she wrote in 2011, when I was recovering from surgery. I care about and love you and want you to be well. Suggesting that I should cut myself some slack, she proposed a “week of experimental self-love.” Why do we ride ourselves so hard? she asked. I remember getting angry at myself during chemotherapy for not using the time to figure out a better way to make a living & also why wasn’t I writing?

We were always writing, or thinking about writing, or sharing our strategies for getting some writing done. Have you noticed that I’m writing on a typewriter? Melissa asked. It’s an IBM Selectric II in an olive-ish green; I got it years ago on ebay but almost immediately it went down to the storage locker in the basement of my building because it took up about ¼ of my apartment. Now I have it at the cabin, where it belongs. I can’t tell you how much I love it—how much more comfortable than a computer it feels.… I took it to a typewriter repairman in the Flatiron district, a real chatterbox, who namedropped his clients, Sam Shepherd among other notable typists, whose names I can’t remember, because instead of listening I was thinking, Are you ever going to begin repairing my typewriter? Otherwise, I might have written a little Talk of the Town or Shouts and Murmurs piece about the experience—can’t you see the two or three columns with a little scribble of a typewriter? What I mean is, if I’d listened, I might’ve spent days on end coming up with a draft, revised it a hundred times, finally sent it to the NYer and had it rejected.

Have I mentioned how much I loved those letters? I loved everything about them. And I loved the act of letter-writing itself: the selection and the folding of paper, the scritch of the pen, the envelope and stamp, the walk to the mailbox, and the anticipation of a reply.

I learned that Melissa’s cancer had recurred not by letter but by phone, when one of her friends in New York called to tell me the news. (Bad news, in my experience, never comes by letter; it comes by phone.) I wrote to Melissa and told her that I would fly to New York and try to make myself useful, but then Covid hit, and her compromised immune system made a visit unwise.

I sent her more letters. I sent her badly-made collages and cards. You’ve been about the best friend a girl could ask for, she wrote in July of 2020. I am sitting at my desk with your recent letters and postcards spread out in front of me—& then there is the gorgeous sketchbook and the pen so fluid it appears to write by itself.

In addition to losing a beloved friend, I lost a beloved correspondent.She wrote less often; but when she wrote, the sound of her voice suffused every page. She described lazy afternoons spent with her long-term partner (Have I told you how much I love him?) and about her dogs—she adored her dogs—and her affection for the eastern shore. I’m writing to you from the beach—it’s the end of the day but so beautiful people are still swimming (dogs too) and the light is very soft and the ocean not calm but predictable—big swells—perfect, I mean just perfect, & I wish I could give you the peace & contentment I feel.

In the spring of 2022, I wrote several letters without expecting a response. (Melissa’s last letter to me had come months before: I’m sort of wiped out but have wanted to write to you for so long.) I told her that my daughter in New York was pregnant; I would soon have a grandchild. How astonishing was that? I had been pregnant with that daughter when Melissa and I were in grad school, almost thirty-four years before.

In July of 2022 I flew to New York to meet the new grandchild, writing to Melissa to tell her that I hoped to be visiting often, and also hoped—now that Covid was easing—that I could see her in Manhattan soon. While the new grandchild was sleeping, I got a phone call and was told that Melissa had died.

In addition to losing a beloved friend, I lost a beloved correspondent. I feel the impulse to write to her when I see the coil of postage stamps on my desk, or when I read a book that I wish she could read, or when I remember something she said to me almost forty years ago in the kitchen of my student apartment, papers strewn across the table and a seashell between us as an ashtray, the two of us talking and arguing and laughing, before her cancer or the bicycle accident that nearly killed her, before I moved away and had children, before we needed to send each other letters, because we saw each other almost every day.

So many of Melissa’s letters begin with an apology for not writing sooner (sorry sorry sorry) and end with postscripts (PPS I miss you! PPPS Write back soon!) as if she was reluctant for the writing to end.

I can’t tell you how much I love getting your letters, she wrote; I felt the same.

If I were writing to her now, which I suppose I am, I would tell her that I will remember her—remember you—among the things in life you loved best: your dogs, a stack of good books, a notebook and pen, and one of those perfect oceanside afternoons with your partner, which you described so clearly in one of your letters I felt I could see it:

…a gorgeous day, cloudless—and then we went to the bay for the sunset. The fish were jumping out of the water—high & whole schools of them. It felt like seeing a sky full of shooting stars.

__________________________________

The English Experience by Julie Schumacher is available August 15th from Doubleday Books.