Joshua Bennett on the Fullness of Black Life in a Time of Siege

The Author of Owed Talks to Jesse McCarthy About BLM, Black Comedy, Teaching and More

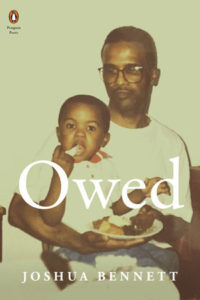

Poet, performer, and scholar Joshua Bennett is the author of three books of poetry and criticism: The Sobbing School (Penguin, 2016)—winner of the National Poetry Series and a finalist for an NAACP Image Award—Being Property Once Myself (Harvard University Press, 2020) and Owed (Penguin, 2020).

Dr. Bennett is the Mellon Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing at Dartmouth. His writing has been published in Best American Poetry, The New York Times, The Paris Review, Poetry and elsewhere. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Ford Foundation, MIT, and the Society of Fellows at Harvard University. His first work of narrative nonfiction, Spoken Word: A Cultural History, is forthcoming from Knopf.

In the following conversation, Jesse McCarthy speaks to Dr. Bennett about Owed, his latest release.

*

Jesse McCarthy: Your first book of poetry, The Sobbing School, came out in 2016 and you wrote a lot of that book in 2014-2015 as protests over police violence in Ferguson and around the country were coalescing behind the Black Lives Matter movement. Your new book, Owed, lands this month in the middle of a wave of protests against repeated police violence and a pandemic that is disproportionately taking Black lives.

I’m going to begin by asking a hard and probably unfair question that I think a lot of people are nevertheless asking themselves: is it possible, or for that matter desirable, to make art without being overwhelmed by the pressures of political and social emergency?

Joshua Bennett: At this point, it’s hard for me to imagine writing from a vantage that isn’t in some way largely informed by the material conditions which, in some sense, are the overt object of the current protests: anti-Blackness as a structural logic of the modern world system. The cities and towns where the killings take place change. The litany of names lengthens. But the larger symbolic order—in which these public ritual killings serve a specific, semiotic purpose—remains more or less intact.

Owed differs from The Sobbing School in that I think it explicitly, at every turn, asserts an emphasis on Black sociality, Black celebration, in the midst of this ongoing, state-sanctioned terror, what you have so aptly described here as an unceasing emergency. I wouldn’t say that I ever feel overwhelmed, exactly. I consider it a great privilege to make a living putting words on the page and teaching young people about the Black aesthetic tradition that helped make my life possible.

But I am doing my best these days to think more critically about the sounds and images I interact with online. I still remember, quite clearly, sitting in a classroom in Harlem toward the end of graduate school, watching Christina Sharpe give a presentation on what would eventually become In The Wake. To open, she said something along the lines of “I don’t show images of dead Black people.”

That felt to me then like a certain kind of revelation. And so, part of what I’m after in this book is a dogged emphasis on life itself. Black life itself, in its fullness.

JM: This new book is deeply concerned with form. You are already punning on it in your title; the poem “Owed To The High, as if to remind us that they are still there—still troubled and -Top Fade” is, among other things, a magnificent typographical pun. But you’re also concerned with the form of everyday life in Black communities whose characters and voices resonate throughout this book.

The flip side of that pun is, of course, an allusion to reparations. Are you implying that poetry makes demands on us—and on you—that connect aesthetic or formal concerns with ethical ones?

JB: In my own practice, the aesthetic and ethical concerns are largely inextricable. My ongoing attempt to reflect a certain kind of beauty on the page is rooted in the fact that I come from a people who are systematically denied certain forms of beauty, critical attention, loving study, in their everyday lives.

Owed is, fundamentally, a book about repair. About reparations not only as a kind of monetary exchange or redistribution of material resources, but a larger social and psychic shift through which we can amend our relationship to Black spaces, Black vernacular, Black objects and performance and ways of knowing.

“What is lost in pursuit of a dominant vision of the good life and all that it offers, all that it costs?”The specific poem you invoked here, for example, is largely about my own relationship to my hair; the various ways that even as a small boy I was taught to think of it as something to be tamed, shorn, hidden from view. Unlearning that relationship to one’s body in an anti-Black world has long been a central concern of Black poetry in the Americas. My aim is to make a meaningful contribution to that larger assemblage of voices.

JM: You have a poem about Lebron James in this collection that refers at one point to “the chosen / few of us” and one of the recurring voices in these poems is that of “Token” who shows up at the beginning of each section troubling the lyric waters around them. Would it be fair to say that this collection is concerned in different ways with what is sometimes called “Black excellence,” an expression that can be aspirational and inspiring, but also inevitably isolating and even merciless?

JB: I haven’t ever really used “Black excellence” in print or casual conversation but am interested in it to the extent that it might describe a certain set of everyday practices that would otherwise fly underneath the radar (my older sister singing lead alto in the teen choir, the girls on the block playing double-dutch, the good brother on the summertime corner selling cherry, coconut and mango icee’s out of the tubs in his silver cart).

Part of what I’m working through in those “Token” poems is what it means to be a Black person that is raised in the midst of this sort of everyday beauty and brilliance, but spends the majority of his young adulthood and adult life studying and working in spaces where institutional belonging, elite status, is established over and against these very ways of being-together, these varied forms of daily sustenance and delight.

What is lost in pursuit of a dominant vision of the good life and all that it offers, all that it costs? The Token character is wrestling with those sorts of questions throughout the book, without ever coming to any sort of easy conclusions.

JM: One of my favorite lines from this collection is: “Now, I hear / the word America & think first of my father’s loneliness.” There are extended meditations on kinship throughout your poetry, on its meaning and qualities, sometimes on its own terms, but often under duress. Do you think Black kinship and Black poetry share a special bond—a traditional dialogue that you are, in a sense, extending?

JB: I hope so. I often say that the first poets I ever saw were preachers, but it’s equally true that a number of the first truly excellent teachers, writers, musicians and orators I encountered were family members. It was my big sister who first introduced me to the art of storytelling. My mother who ran the Vacation Bible School at our home church and was also a kind of pedagogical model beyond the boundaries of that building in all sorts of other ways.

Outside of those relationships, I’ve long been interested in the unique spaces Black poetry has historically created for intergenerational sharing of all kinds (I’m currently in the process of working on an essay centered around June Jordan’s early 1970s poetry workshop at the Church of the Open Door in Brooklyn, the Voice of the Children, for example) and have done my best to develop that interest into various forms of public programming over the years.

Poems are just one of the many forms—and our people truly have no shortage of methods on this front—that we use to articulate the abiding love that makes the present world livable.

JM: We’re living in serious, some would say damn-near apocalyptic times, but one aspect that people (who don’t already know your work) might not anticipate about these poems is how much humor plays a part in them. We often turn to the comedian and to the comic, from Bert Williams to Moms Mabley or Dave Chapelle, as a way to get through the worst times. Zora Neale Hurston’s wit and sly signifying are important to your last book. Does humor come naturally into a poem for you, do you think of it as having a special function?

JB: Comedy was such an important part of my watching and listening practices as a young person (The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Martin, Moesha, Family Matters, The Jamie Foxx Show, you name it) and I did my best in this collection to let that aspect of my informal training loose a bit more. In my performances, as well as on the page, humor is a way in. It opens a door in us. Stage banter is its own art form, and is often my favorite part of giving a reading.

“It’s truly astonishing, and heartening, to see the sheer breadth of work that poets online are sharing every single day.”All my favorite writers (you mention Hurston here, but Lucille Clifton, William Matthews, Nikki Giovanni and others come to mind on this front) all have this extra gear in their work, where they can immediately pivot from the most heartbreaking details of a given story to making you laugh aloud moments later. That breadth, that irreducibly human depth, is something I’m always working to hone in my own writing.

JM: There’s so much going on in the poetry world these days. What do you think is the biggest difference or the biggest change you’ve seen in the last five to ten years, going back to when you first started out performing?

JB: Almost certainly the increased importance of social media. My work has reached places I never would have imagined through the internet and allowed me to be in conversation with folks whose work and ideas have transformed the landscape of my life. There are also clearly all sorts of pitfalls that come along with these platforms, but given the mood I’m in right now, sitting here with my dog, Apollo, what immediately comes to mind are the moments where someone I don’t know at all has written me and said they read one of my books, or even a single poem, and that it connected with their own experiences in an impactful way.

It’s difficult to describe how much that means to me. In no small part because the support of those people, those thousands of strangers, has been an integral part of me being able to live a life I never dared to imagine, even as a college student. I didn’t know to dream of it. And now I get to write and read and teach and imagine new worlds alongside my friends for a living.

JM: One aspect of lockdown has been the opportunity to attend readings online that are happening all over the country and all over the world. And I feel like people are more eager than ever to find good books to read and share. What have you been reading lately? And do you have any recommendations for ways folks can follow or learn more about what’s happening in poetry circles near and far?

JB: I just finished reading Bob Kaufman’s Collected Poems on my birthday. Now I’m working through C.L.R. James’s beautiful book on Herman Melville, Mariners, Renegades and Castaways, Jonathan Rosa’s Looking Like a Language, Sounding Like A Race, Sharon Olds’s The Unswept Room, and Trina Greene Brown’s Parenting for Liberation: A Guide to Raising Black Children.

The best advice I can give as far as keeping up with contemporary poetry is to find some of your favorite poets online, then check out what they are reading and who they are reading with. It’s truly astonishing, and heartening, to see the sheer breadth of work that poets online are sharing every single day.

JM: Finally, I know there’s a lot going on—but what are you most looking forward to right now, in your writing and teaching, but also just life in general?

JB: I’m teaching a new course this fall, “Modern Black American Literature: Education, Abolition, Exodus!” that I’m excited about. I also just finished a new book over the summer—one that’s a bit more experimental at the level of genre than my earlier work—and am looking forward to sharing it with folks who know me best in other, more familiar registers.

More than anything else, though, I’m excited to welcome my son into the world in the coming weeks. My wife and I are in the final stages of preparing the house for his arrival, and it’s difficult to explain the sort of joy, and sense of expectation, that have characterized my days as of late. A fair amount of what I’m feeling truly defies description. And for the first time in years, I’m fine with that.

__________________________________

Joshua Bennett’s poetry collection Owed is available now.

Previous Article

When Hunter S. ThompsonRan for Sheriff