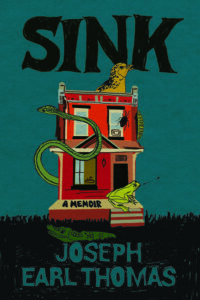

Joseph Earl Thomas on Finding Safety and Comfort in the Hospital

“He lay there all night with a broken half smile on his face, waiting for something to go wrong.”

Back in 1996, when it used to snow still, Joey built an ice fortress to defend against his many enemies. Mika helped. A little, or as best she could, since she was still so little herself. Right up against the Post Office wall on the 4400 block of Paul Street was constructed a monument against humanity. There seemed to be no rush, as the snow fell all day and night forever, and in such a way that it was never exhausted by Joey’s need to use it up.

First, he shoveled as much of it as he could up against the orange-red bricks that shielded the Post Office. Mika followed behind him with snow cuffed in her hands, adding kid-sized lumps on top of the structure. A bulldozer came—courtesy of the state—and moved the rest of the powder up against the wall, but only on Post Office grounds. This was fine. It meant that, from here, Joey needed only to give form to the whiteness that was quickly becoming packed ice. He poked holes in it. He dug tunnels all through the mound and shaped sharp edges on the outside with a skull in the center, like a replica of Castle Grayskull. Mika got stuck inside some of the tunnels and had to be pulled out by one leg, and despite her near popsiclization, she kept laughing every time.

“This is serious,” Joey said.

The view from the top of the fort expanded Joey’s world. With fewer children willing to stay out in the cold for that long, the whole neighborhood became like a polar climate special on Animal Planet, all bare earth masked in cold, white powder, creatures beneath it wanting and waiting and growling and cuddling and warm, or completely unknowable. Joey considered then that he might stumble into a polar bear or maybe capture an arctic fox to love and to have and hold as a trained assassin, a rabies-laden guardian always tense around strangers but exceedingly loving toward him. He could domesticate and breed them even. Their tails would curl up like dogs and they’d want to snuggle all the time. He could name them Eevee, Vaporeon, and Flareon, respectively and in that order.

Or a narwhal might pop up from a snow mound cracking open concrete and exposing the water beneath a dry ass city of trash and sewage and scum. There was definitely water if you went deep enough, somewhere down there. But there was also security in the blanket of white powder over everything. He couldn’t even see the busted cars in the lot across the street or tell that the fence had barbed wire on it, everything uniform and in its right place and silent instead. The streets were full of rage, but felt empty. Snow would not stop falling.

“This is the best fort in human history,” he told his little sister.

Mika, wearing checker-patterned oven mitts to keep warm and one of those big puffy jackets that make little kids look like marshmallows, stared up at him like he was insane. She looked bored tucking her cookware-covered hands in her jacket pockets and trying not to slide down off the top of the fort.

Joey went on. “This fort,” he said, “is gonna protect us from bears and yetis.” By which he really meant Ray and Darren and other neighborhood boys but also Popop and the adults in the house who he wished were actually just bears and yetis.

“Joey,” Mika said, “I’m cold.”

Joey had never seen a black person so blue. She looked almost like a Smurf and could hardly quit trembling enough to speak.

“You should go inside by the oven,” Joey said. “Or else you gonna die.”

And off his sister went, tumbling down the fort and waddling inside to warm up by the oven, leaving Joey alone outside, staring through the blizzard, dreaming to himself and unable to feel his hands or feet in the slightest. He could almost forget he had a body.

Joey woke up in the hospital. He wasn’t sure it was a hospital at first since it was the first time he’d been placed in such a bed, but from the immediate cleanliness and warmth, he knew it was definitely not home. Outside the window he could hardly locate himself with all the snow, except for a single sign, “Max’s,” the cheesesteak place at Broad and Erie where he’d been dragged along by various adults so they could get drugs, believing that he, as a child, was unaware of the process.

These were memories that, despite Joey’s later-in-life vomiting of blue liquid and oiled animal on that corner after eating two feet of cow-bathed bread, fake cheese, and onions, smothered in salt pepper ketchup mayonnaise across the street from a gentleman’s club after one angry black boy shot another angry black boy, he could never forget as a kind of origin story. Alone in his new room, he thought about the fort.

He figured that being in a clean, warm place like the hospital room would eventually mean he’d owe someone something, whereas the fort was all his. With any luck, it would stand strong the whole time and wait patiently for his return. It turned out his asthma was acting up, and nurses, one with blond hair who looked like Winry from Fullmetal Alchemist, came in to give him breathing treatments several times a day. He hated holding the machine to his mouth because the smoke felt dangerous, but he’d never gotten so much food and attention before.

Three hot meals a day—none of which included Oodles and Noodles—was a certain kind of paradise. Joey spotted nary a roach during his stay, which also felt like a privilege he didn’t deserve. He could sleep soundly, on his back even, with his eyes closed like he saw white kids fall asleep in movies after their mommies and daddies read them bedtime stories. Everything felt so unreal. And it made him guilty, so he lay there all night with a broken half smile on his face, waiting for something to go wrong.

Pneumonia. It didn’t hurt. All he understood then was something about lungs and breathing. But when asked if he’d ever had trouble breathing like this before, at home, he kept lying and saying no. Pneumonia wasn’t a real physical ailment to the boy, just a new word to keep him warm and clean and fed. He spelled it like “Namonia” for years, which also looked on paper more like a virus with a mind of its own that would talk to you and plot world domination rather than the dumb bacterium that caused Joey’s lungs to swell but not burst. Joey thought a lot in the hospital about how none of the fictional characters he loved ever got sick, and neither did Popop.

Perhaps because they didn’t have time to inside the story they were telling themselves. Food distracted. Joey ate sausage and eggs for breakfast, beef stroganoff for lunch, and lasagna for dinner. His bed was lumpy, with thin white sheets, but the room was warmer than the inside of that fort or the apartment on Paul Street. Everything was clean and white. To the right of his bed was a spotless window where he watched the snow crush Erie Avenue all day and night.

When he wasn’t looking outside or eating, Joey watched TV in the hospital room despite his suspicions that The Cosby Show was set up to convince him of something deeply nefarious, an alternate reality that hurt but was too hard to express. Winry and her friends kept checking on him, but they never complained about the shows he wanted to watch: Toonami mostly, Cowboy Bebop and Outlaw Star, Zoids and Mobile Suit Gundam. They’d come back with a new friend each time, though, giggling and saying that he was cute but just so shy. Why is he so afraid, they said. The boy refused to answer most of their questions and was stuck on yes and no and asking for more food or to change the channel.

They discussed getting a social worker to talk to him, but there was only one for the whole hospital and she was busy with the more serious cases. There were other children, Joey imagined, who’d been quite obviously beaten bloody or shot by their parents or legal guardians, of whom he knew there were plenty, and in this, he felt grateful that he didn’t get punched in the face or shot at home, and equally grateful that he did not, in this particular moment, have to be home or talk to any social workers.

The nurses went on. He’s so cute, they said. Every hour at the door, trying not to disturb him. Every hour.

If there were people living who wanted nothing in return…where were all of these people outside of the hospital?After a while, Joey was weirded out by them. They were too carefree, and smiled a lot. They flashed all their teeth too much, and Joey knew that for other animals this was a threat, a promise. They’re like cartoon princesses, he thought, who might bite if provoked. The boy wondered why they were being so nice to him. It was like they had a plan to bite eventually, just not right now. They would tenderize him into complacency first. Or maybe they wanted something from him. They would never say this up front, because the villain always waits until you have no means of escape to offer false choices.

After they’d taken care of him, of course, they would suggest what he owed, what he needed to do, to pay. They might say he had to let them touch his winkey, maybe even all at once, because fair was fair, and they’d fed him for free. And he’d better use his winkey the right way or else they would just cook and eat him. He was doomed either way because even if he could do it right, he would get in trouble for touching white girls, and if he said no, they would hurt him or just be really mean and he would no longer have any food or a place to stay. He knew, deep down, that he would have to lick their coochies, and do it right, or they would get mad and threaten him. He didn’t know which route to take and so he got quieter and quieter, which only made the nurses check up on him more.

But nothing ever happened. No one ever asked him for anything except to take his temperature. Why then, the boy thought, are they being so nice to me? If there were people living who wanted nothing in return, who bore no grudge against him for being a child, where were all of these people outside of the hospital? It made him more afraid to go back home.

The nurses, he then found, treated him like Steve Irwin finding a little lizard in the desert, doting over his completely regular body with infinite affection and pet names. What a beaut! they might as well have been saying. Look at that pretty little boy there! But then it occurred to Joey that there were parents who generally treated their children this way, and the contradiction just made him angry. He wanted to be an animal, wondered what it would be like to be a bat, a wolf, a snake, and for no one else’s sake but his own, with pure and easy evolutionary drives that bred family only toward the intensification of survival.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Sink: A Memoir by Joseph Earl Thomas. Copyright © 2023. Available from Grand Central, a division of Hachette Book Group.