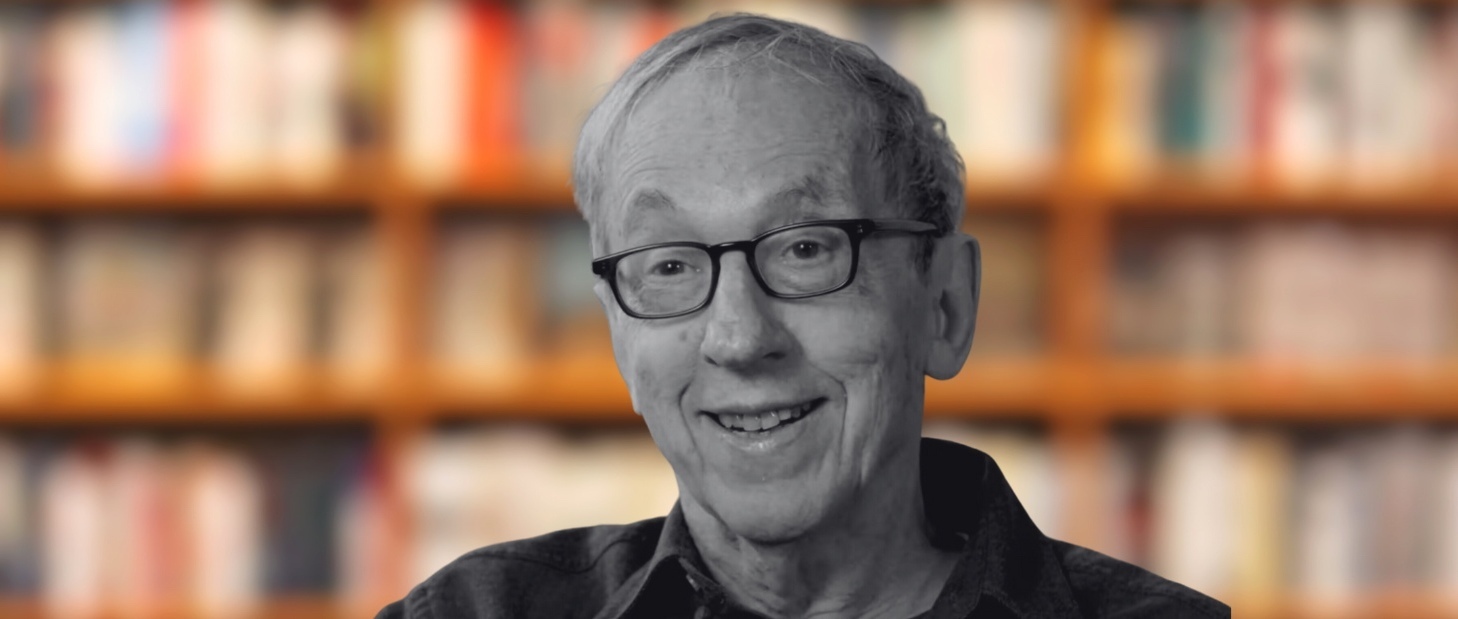

Jonathan Galassi Remembers His Friend, the Great Robert Gottlieb

“The last and arguably the most successful of the editor-publishers.”

Robert Gottlieb, the great American editor who died last month at the age of ninety-two, often said that there were two ways of being a publisher: to follow, i.e., give the people what they knew they wanted; or lead: show them what you knew they ought to want. Bob was brilliant at both. He was the last and arguably the most successful of the editor-publishers, those larger-than-life characters whose taste and personality shaped the houses that they made synonymous with themselves. (Today’s conglomerates tend to eschew these showboats in favor of stability, not to say predictability.)

Starting in 1968, Bob set the agenda at Alfred A. Knopf, the most storied white glove publisher of an earlier era (Willa Cather, Thomas Mann, Albert Camus), which had grown quiescent in its founder’s golden years. Soon, he had melded his own brand of big-tent panache, energy, and discernment with Knopf’s cachet.

Bob had made his mark at Simon & Schuster editing pathbreaking books like Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything, The American Way of Death by Jessica Mitford, and, most famously, Joseph Heller’s absurdist masterpiece Catch-22. Its original title had been Catch-18 but, learning that Leon Uris’s Mila 18 was about to come out, Gottlieb suggested “Catch-22” because, as he rightly said, it was funnier. At Knopf he made equally adventurous choices, and excelled in the ways books were presented and marketed. He’d learned at S&S that publishing was in large part merchandising and relished every aspect of the process. He was the king of maximalist flap copy and the doyen of book advertising; Knopf’s stark declarative ads (back when there still were newspaper ads) were the envy of the industry. The sales and marketing departments adored him because his predictions were so often right.

In many ways Gottlieb was the avatar of what used to be known as the “best of breed” publisher. He called himself “kind of a word whore” who would “read anything from Racine to a nurse romance, if it’s a good nurse romance.” He was as enthusiastic and incisive about Michael Crichton, Len Deighton, Thomas Tryon, and Miss Piggy as he was about Robert Caro, Cynthia Ozick, John le Carré, Doris Lessing, and John Cheever. Having studied at Cambridge, he had a long list of stellar British authors from Julian Barnes to Antonia Fraser and any number of her writing daughters and was deeply read in world literature (he boasted of single-handedly keeping Tanizaki’s The Makioka Sisters in print for years); but the primary focus of his publishing was deeply American.

In many ways Gottlieb was the avatar of what used to be known as the “best of breed” publisher.

Gottlieb didn’t believe in big advances, and book auctions didn’t really become standard procedure until he left the business. Agents made deals with him because their authors wanted to be published by Knopf. He was famous for reading a writer’s book overnight. “Why wait?” he asked, a bit disingenuously, as if doing anything else was just wasting time. Anyone who wants to understand his editing techniques should read his 1994 Paris Review interview, which in fact is an interview of many of his most renowned authors, talking about his chameleon ways of getting them to give him the best of themselves. As his longtime friend the agent Lyn Nesbit observed: “Bob takes [his] enormous ego and lends it to the writer, thereby reinforcing the writer’s ego. Bob is very generous with his ego.”

There was nothing physically prepossessing about Gottlieb’s glamour. He was the original nerdy bookworm, who looked like Woody Allen’s scruffier brother. Recently I found myself examining a picture of Bob with his great friend Toni Morrison. What was so arresting about it—was it Morrison’s gimlet eye as she stared up at a jocular Bob? No; it was that Bob was wearing a suit!—albeit without a tie. I’d never seen that before. He often went around the office in his socks, in the same clothes he’d worn as a Columbia student. And he disdained the rituals of the trade, like the time-honored editor’s lunch with author or agent. “I don’t have to have lunch,” he told me once. “But you do.”

Bob’s aura enhaloed him in the Knopf offices, which some felt had the atmosphere of a cult. The company amour propre had begun with Alfred and Blanche, but it exfoliated bigly in the Gottlieb era and many of its denizens basked in its We Happy Few specialness. Normalsville, an intricate HO-scale model world on a ping-pong table in an unused office, embodied the boredom of Elsewhere.

Bob’s experience of psychoanalysis no doubt informed his ways with his authors. He made no secret of his difficulties with his own father, and his relations with other males could be fraught. John Cheever’s daughter Susan says that he and Bob were never really friends. Robert Caro, storied biographer of Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson, asserts that Gottlieb was very, very chary with compliments. In Turn Every Page, Bob’s daughter Lizzie’s brilliant 2022 film about the life-long Caro-Gottlieb relationship, we see two spiky old men still irritating each other, still arguing over punctuation, across fifty years of collaboration, waiting to see who will be the first to go.

In Turn Every Page, Bob’s daughter Lizzie’s brilliant 2022 film about the life-long Caro-Gottlieb relationship, we see two spiky old men still irritating each other, still arguing over punctuation, across fifty years of collaboration, waiting to see who will be the first to go.

His mother, on the other hand, thought Bob walked on water, and his life was rich in friendships with older women–not to mention the gifted, largely female staff at Knopf, some of whom remain at the house today—-or did, until the Great Housecleaning at Random House this month wiped away much of the old Knopf culture, and lots beside. Many of Bob’s great editorial triumphs involved women writers—and stars—from Morrison to Mitford to Barbara Tuchman to Nora Ephron, Brooke Hayward, “Betty” Bacall, and Katharine Hepburn. His long, companionable marriage to the actress Maria Tucci was itself a work of art inspired by mutual respect, toleration, and affection.

At the moment, I’m working with Susan Cheever on her astute reconsideration of her father’s short fiction. In it, she recounts how Bob persuaded a reluctant Cheever to collect sixty-one of his admired but more or less forgotten stories, written over four decades, in one magisterial volume. The Stories of John Cheever, in its iconic red jacket, was an enormous publishing event and a phenomenal bestseller when it appeared in 1978, not long after his last novel, Falconer. It won Cheever a Pulitzer Prize and ushered in the upward revaluation of his work that crowned his final years. As Susan shows, it was Gottlieb’s deep understanding and love of the work, his persistent coddling and coaxing of a diffident author, and his instinct for how best to present him, that changed Cheever’s fortunes, and American letters.

It’s hard to believe he was there for only twenty years. In my imagination and for many others, I’d hazard, he remains the tentpole of so much of what our business has been at its best. But in 1987 he surprised everyone by leaving Knopf, entrusting it to his London colleague Sonny Mehta, whom Bob correctly judged had the commercial finesse and literary chops to carry the house forward. Bob moved, at the behest of S. I. Newhouse, who owned both Random House and The New Yorker, to succeed its editor William Shawn, another storied grandee past his sell-by date. Gottlieb’s tenure at the magazine, which he described as “curatorial,” reflected the long-established tastes of the magazine, many of which dovetailed by then with his own. Which meant that his editorial outlook was no longer as cutting edge as it had been. In 1992 he was replaced by Tina Brown, whose whirlwind tenure lasted until 1998, when David Remnick stepped in to combine currency and quality in a formula that has set the tone for a generation.

Gottlieb returned to editing at Knopf, where he kept on having great editorial successes, including memoirs by Bill Clinton and Katharine Graham, and wrote for the New York Times Book Review, The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, and elsewhere. And he wrote books, most notably his brash and infectious memoir, Avid Reader, published to wide acclaim by FSG in 2016. (A new imprint at his alma mater S&S, named in honor of his book, and him, was inaugurated in 2018.)

Bob had another passion: dance, and here, too, he was all in. He published most of the major dance books of his era and served on the board of New York City Ballet in the 1970s and 1980s, where he programmed performances, never shying from wading into controversy. Later, he was closely involved in the fortunes of the Miami City Ballet.

My Swedish sister-in-law fell under Bob’s spell when she helped him gather photos and other materials for his last book, an over-the-top study of the most mysterious and unknowable of stars, Greta Garbo. A couple of months before he died, he and Kerstin shared a four-hour lunch at his favorite coffee shop, after which he insisted on walking her, with great effort, to the subway. When I told Maria this, she responded that he’d never been all that good at walking. True, perhaps; but his passionate engagement, his chivalry and grit, were all on display that afternoon. His loving grasp on life never left him, and it added immeasurably to our world.

_________________________

The featured image is adapted from a still from Turn Every Page: The Adventures of Robert Caro and Robert Gottlieb, a documentary by Lizzie Gottlieb.

Jonathan Galassi

Jonathan Galassi is chairman and executive editor of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, which published many of Bob Gottlieb’s books.