John Keene on the Life and Literary Legacy of Essex Hemphill an Early Poetic Chronicler of Black Queer Life

In Praise of an Early Poetic Chronicler of Black Queer Life

Throughout Essex Hemphill’s poetry, what we registered was his attentiveness to craft as well as statement, to the possibilities of performance, of form, of the line, and to the expressive content, which is to say the lives and stories, his life and story, that these lines bore and made visible. He was a lyric poet to his core, and a political poet who knew that the most devastating critique could hinge on many of poetry’s numerous resources, any of which he wielded when needed.

What we also appreciated was how open he was to self-reflection and reassessment, and how much he anticipated and opened up spaces for an array of poetics and poetries to come. I, like so many other writers of my generation and subsequent generations, would not be publishing today if it weren’t for Essex Hemphill’s example, his courage and daring, and his fearlessness and willingness to place his art on the stage and page before audiences and readers.

Rereading and assembling these poems took on a particular poignancy for me, because I had the pleasure, as a young writer, not only of meeting and interviewing Hemphill in 1989, as part of the Dark Room Writing Collective’s reading series, based then in Cambridge, Massachusetts, but of having Hemphill serve as one of my first editors, when he selected and then proceeded to help me refine one of my first published short stories for the anthology Brother to Brother. He was generous but rigorous in his comments, never failing to suggest striking or rewriting passages that I was wedded to, a process which, I realized on rereading, showed me the breadth of his talents as a reader and writer.

Co-editing this collection of poems, I would not deign to change a word, but in studying Hemphill’s poetics, how he drafted, ordered, and revised his poems, I continue to learn invaluable lessons about poetic craft and literary art in general. I also believe his generosity of spirit and intellectual and artistic rigor shine through in these selected poems.

He was a lyric poet to his core, and a political poet who knew that the most devastating critique could hinge on many of poetry’s numerous resources, any of which he wielded when needed.

Reading Hemphill’s work reminds me not only of his remarkable individual talent and many gifts as a poet, but also that he was one of the leading and most accomplished figures in a generation of Black gay, lesbian, transgender, and queer writers and artists who came of age in the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Arts, Gay Liberation and LGBTQ Equality, Women’s Rights, Lesbian Separatist, and Black and Third World Feminism movements. His work, like that of his peers, powerfully reflected, acknowledged, assimilated, and advanced the best lessons of these movements.

Like a number of his Black LGBTQ peers, Hemphill began publishing and performing his work as more spaces—journals, little magazines, anthologies, and small presses, many edited and published by Black LGBTQ writers and artists, along with reading and screening venues, including bookstores, colleges and universities, conferences, and nightclubs, etc.—opened up and welcomed these artists’ visions and voices. For a moment, a flowering of Black LGBTQ literary and artistic production was visible to anyone paying attention. Hemphill even started his own small press, Be Bop Books, in Washington, D.C.

I am also reminded that within a few years, the AIDS pandemic took so many of these talented writers from us, often abruptly and before many could realize the rich promise of the work they had shared with the world; and so this selected volume stands as a tribute to Hemphill’s distinctive poetics, but also should send us back to those many poets, writers, artists, whom we lost prematurely to AIDS and other social, political, and economic depredations, especially as we witness yet more waves of anti-LGBTQ, racist, misogynistic, and classist backlash to the achievements these movements have made.

In conclusion, co-editing this volume was a labor of deep love and gratitude and tribute. It is our sincere hope that readers will return to it regularly and seek out more of Essex Hemphill’s work and that of his LGBTQ contemporaries, who created vital and enduring artistic and activist spaces—fusing the two in ways we might take for granted today—for those who would come after them, making possible the ever-expanding universe of letters in American, African American, and African Diasporic LGBTQ writing that we appreciate today.

–John Keene

*

“Heavy Breathing”

… and the Negro every day lower, more cowardly, more sterile, less profound, more spent beyond himself, more separate from himself, more cunning with himself, less straight to himself,

I accept, I accept it all …

–Aimé Césaire,

Return to My Native Land

At the end of heavy breathing,

very little of my focus intentional,

I cross against the light of Mecca.

I recall few instances of piety

and strict obedience.

Nationalism disillusioned me.

My reflections can be traced

to protest slogans

and enchanted graffiti.

My sentiments—whimsical—

the dreams of a young, yearning bride.

Yes, I possess a mouth such as hers:

red, petulant, brutally pouting;

or at times I’m insatiable—

the vampire in the garden, demented

by the blood of a succulent cock.

I prowl in scant sheaths of latex.

I harbor no shame.

I solicit no pity.

I celebrate my natural tendencies,

photosynthesis, erotic customs.

I allow myself to dream of roses

though I know

the bloody war continues.

I am only sure of this:

I continue to awaken

in a rumpled black suit.

Pockets bulging with tools

and ancestral fossils.

A crusty wool suit

with salt on its collar.

I continue to awaken

shell-shocked, wondering

where I come from

beyond mother’s womb,

father’s sperm.

My past may be lost

beyond the Carolinas

North and South.

I may not recognize

the authenticity

of my Negritude

so slowly I awaken.

Silence continues

dismantling chromosomes.

Tampering with genetic codes.

I am sure of this

as I witness Washington

change its eye color

from brown to blue;

what kind of mutants are we now?

Why is some destruction so beautiful?

Do you think I could walk pleasantly?

and well-suited toward annihilation?

with a scrotal sack full

of primordial loneliness

swinging between my legs

like solid bells?

I am eager to burn

this threadbare masculinity,

this perpetual black suit

I have outgrown.

At the end of heavy breathing,

at the beginning of grief and terror,

on the X2, the bus I call a slave ship.

The majority of its riders Black.

Pressed to journey to Northeast

into voodoo ghettos

festering on the knuckles

of the “Negro Dream.”

The X2 is a risky ride.

A cargo of block boys, urban pirates,

the Colt 45 and gold-neck-chain crew

are all part of this voyage,

like me, rooted to something here.

The women usually sit

at the front.

The unfortunate ones

who must ride in the back

with the fellas

often endure foul remarks;

the fellas are quick to call them

out of name, as if all females

between eight and eighty

are simply pussies with legs.

The timid men, scattered among

the boat crew and crack boys,

the frightened men

pretend invisibility

or fake fraternity

with a wink or nod.

Or they look the other way.

They have a sister on another bus,

a mother on some other train

enduring this same treatment.

There is never any protest.

No peer restraint. No control.

No one hollered STOP!

for Mrs. Fuller,

a Black mother murdered

in an alley near home.

Her rectum viciously raped

with a pipe. Repeatedly

sodomized repeatedly

sodomized before a crowd

that did not holler STOP!

Some of those watching knew her.

Knew her children.

Knew she was a member of the block.

Every participant was Black.

Every witness was Black.

Some were female and Black.

There was no white man nearby shouting

“BLACK MAN, SHOVE IT IN HER ASS

TAKE SOME CRACK! SHOVE IT IN HER ASS,

AND THE REST OF YOU WATCH!”

At the end of heavy breathing

the funerals of my brothers

force me to wear

this scratchy black suit.

I should be naked

seeding their graves.

I go to the place

where the good feelin’ awaits me

self-destruction in my hand,

kneeling over a fucking toilet,

splattering my insides

in a stinking, shit-stained bowl.

I reduce loneliness to cheap green rum,

spicy chicken, glittering vomit.

I go to the place

where danger awaits me,

cake-walking

a precarious curb

on a comer

where the absence of doo-wop

is frightening.

The evidence of war

and extinction surround me.

I wanted to stay warm

at the bar,

play to the mischief,

the danger beneath a mustache.

The drag queen’s perfume

lingers in my sweater

long after she dances

out of the low-rent light,

the cheap shots and catcalls

that demean bravery.

And though the room

is a little cold and shabby,

the music grating,

the drinks a little weak,

we are here

witnessing the popular one

in every boy’s town.

A diva by design.

Giving us silicone titties

and dramatic lip synch.

We’re crotch to ass,

shoulder to shoulder,

buddy to buddy,

squeezed in sleaze.

We want her to work us.

We throw money

at her feet.

We want her to work us,

let us see

the naked ass of truth.

We whistle for it,

applaud, shout vulgarities.

We dance like beasts

near the edge of light,

choking drinks.

Clutching money.

And here I am,

flying high

without ever leaving the ground

three rums firing me up.

The floor swirling.

Music thumping at my temple.

In the morning

I’ll be all right.

I know I’m hooked on the boy

who makes slaves out of men

I’m an oversexed

well-hung

Black Queen

influenced

by phrases like

“the repetition of beauty.”

And you want me to sing

“We Shall Overcome?”

Do you daddy daddy

do you want me to coo

for your approval?

Do you want me

to squeeze my lips together

and suck you in?

Will I be a “brother” then?

I’m an oversexed

well-hung

Black Queen

influenced

by phrases like

“I am the love that dare not speak its name.”

And you want me to sing

“We Shall Overcome”?

Do you daddy daddy

do you want me to coo

for your approval?

Do you want me

to open my hole

and pull you in?

Will I be “visible” then?

I’m an oversexed

well-hung

Black Queen

influenced

by phrases like

“Silence = death.”

Dearly Beloved,

my flesh like all flesh

will be served

at the feast of worms.

I am looking

for signs of God

as I sodomize my prayers.

I move in and out of love

and pursuits of liberty,

spoon-fed on hypocrisy.

I throw up gasoline

and rubber bullets,

an environmental reflex.

Shackled to shimmy and shame,

I jam the freeway

with my vertigo. I return

to the beginning, to the opening of time

and wounds. I dance

in the searchlight

of a police cruiser.

I know I don’t live here anymore

to witness.

I have been in the bathroom weeping

as silently as I could.

I don’t want to alarm

the other young men.

It wasn’t always this way.

I used to grin.

I used to dance.

The streets weren’t always

sick with blood,

sick with drugs.

My life seems to be

marked down

for quick removal

from the shelf.

When I fuck

the salt tastes sweet.

At the end of heavy breathing

for the price of the ticket

we pay dearly, don’t we darling?

Searching for evidence

of things not seen.

I am looking

for Giovanni’s room

in this bathhouse.

I know he’s here.

I cruise a black maze,

my white sail blowing full.

I wind my way through corridors

lined with identical doors

left ajar, slammed shut,

or thrown open to the dark.

Some rooms are lit and empty,

their previous tenant

soon-to-be-wiped-away,

then another will arrive

with towels and sheets.

We buy time here

so we can fuck each other.

Everyone hasn’t gone to the moon.

Some of us are still here,

breathing heavy,

navigating this deadly

sexual turbulence;

perhaps we are

the unlucky ones.

Occasionally I long

for a dead man

I never slept with.

I saw you one night

in a dark room

caught in the bounce of light

from the corridor.

You were intent

on throwing dick

into the depths

of a squirming man

bent to the floor,

blood rushing

to both your heads.

I wanted to give you

my sweet man pussy,

but you grunted me away

and all other Black men

who tried to be near you.

Our beautiful nigga lips and limbs

stirred no desire in you.

Instead you chose blonde,

milk-toned creatures to bed.

But you were still one of us,

dark like us, despised like us.

Occasionally I long

to fuck a dead man

I never slept with.

I pump up my temperature

imagining his touch

as I stroke my wishbone,

wanting to raise him up alive,

wanting my fallen seed

to produce him full-grown

and breathing heavy

when it shoots

across my chest;

wanting him upon me,

alive and aggressive,

intent on his sweet buggery

even if my eyes do

lack a trace of blue

At the end of heavy breathing

the fire quickly diminishes.

Proof dries on my stomach.

I open my eyes, regret

I returned without my companion,

who moments ago held my nipple

bitten between his teeth,

as I thrashed about

on the mercy of his hand

whimpering in tongues.

At the end of heavy breathing

does it come to this?

Filtering language of necessity?

Stripping it of honesty?

Burning it with fissures

that have nothing to do with God?

The absolute evidence of place.

A common roof, discarded

rubbers, umbrellas,

the scratchy disc of memory.

The fatal glass slipper.

The sublimations

that make our erections falter.

At the end of heavy breathing

who will be responsible

for the destruction of human love?

Who are the heartless

sons of bitches

sucking blood from dreams

as they are born?

Who has the guts

to come forward

and testify?

Who will save

our sweet world?

We were promised

this would be a nigga fantasy

on the scale of Oz.

Instead we’re humiliated,

disenchanted, suspicious.

I ask the scandal-infested leadership

“What is your malfunction? Tell us

how your automatic weapons

differ from the rest.”

They respond with hand jive,

hoodoo hollering,

excuses to powder the nose,

or they simply disappear

like large sums of money.

And you want me to give you

a mandatory vote

because we are both Black

and descendants of oppression?

What will I get in return?

Hush money from the recreation fund?

A kilo of cocaine?

A boy for my bed

and a bimbo for my arm?

A tax break on my new home

west of the ghetto?

You promised

this would be a nigga fantasy

on the scale of Oz.

Instead, it’s “Birth of a Nation”

and the only difference

is the white men

are played in Blackface.

At the end of heavy breathing

as the pickaninny frenzy escalates,

the home crew is illin’

on freak drugs

and afflicted racial pride.

The toll beyond counting,

the shimmering carcasses

all smell the same.

No matter which way

the wind blows

I lose a god

or a friend.

My grieving is too common

to arouse the glance of angels.

My shame is too easy to pick up

like a freak from the park

and go.

Urged to honor paranoia,

trained to trust a dream,

a reverend, hocus-pocus

handshakes; I risk becoming schizoid

shuffling between Black English

and assimilation.

My dreamscape is littered

with effigies of my heroes.

I journey across

my field of vision

raiding the tundra

of my imagination.

Three African rooftops

are aflame in my hand.

Compelled by desperation,

I plunder every bit of love

in my possession.

I am looking for an answer

to drugs and corruption.

I enter the diminishing

circumstance of prayer.

Inside a homemade Baptist church

perched on the edge

of the voodoo ghetto,

the murmurs of believers

rise and fall, exhaled

from a single spotted lung.

The congregation sings

to an out-of-tune piano

while death is rioting,

splashing blood about

like gasoline,

offering pieces of rock

in exchange

for throw-away dreams.

The lines of takers are too long.

Now is the time

to be an undertaker

in the ghetto,

a black dress seamstress.

Now is not the time

to be a Black mother

in the ghetto,

the father of sons,

the daughters of any of them.

At the end of heavy breathing

I engage in arguments

with my ancestral memories.

I’m not content

with nationalist propaganda.

I’m not content

loving my Black life

without question.

The answers of Negritude

are not absolute.

The dream of King

is incomplete.

I probe beneath skin surface.

I argue with my nappy hair,

my thick lips so difficult

to assimilate.

Up and down the block we battle,

cussing, kicking, screaming,

threatening to kill

with bare hands.

At the end of heavy breathing

the dream deferred

is in a museum

under glass and guard.

It costs five dollars

to see it on display.

We spend the day

viewing artifacts,

breathing heavy

on the glass

to see—

the skeletal remains

of black panthers,

pictures of bushes,

canisters of tears.

__________________________________

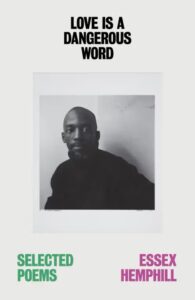

From Love Is a Dangerous Word: Selected Poems by Essex Hemphill, edited by John Keene and Robert F. Reid-Pharr. Copyright © 2025. Available from New Directions.

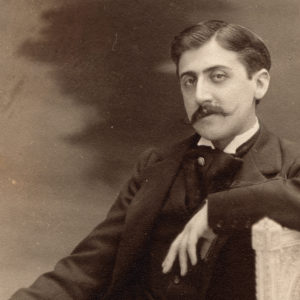

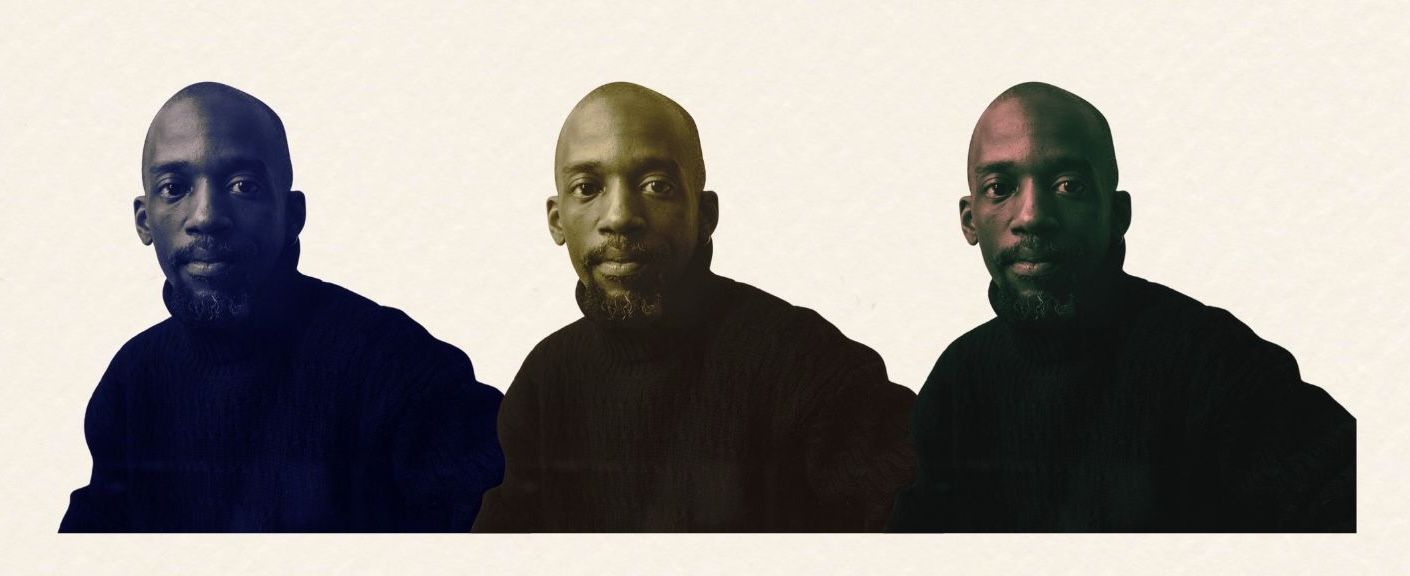

Essex Hemphill

Essex Hemphill (1957–1995) was born in Chicago and raised in Washington, D.C. He was a member of the poetry collective Cinque, a frequent collaborator with the Emmy award-winning filmmaker Marlon Riggs, and the editor of the Lambda Literary Award-winning anthology Brother to Brother: New Writings by Black Gay Men (1991). His collection Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry (1992) won the National Library Association’s Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual New Author Award.