John James Audubon Had More Than a Little Help With Those Bird Paintings

Kenn Kaufman on the Processes of Artistic Collaboration and Imitation

They’re everywhere, those Audubons. Most people in the United States (and many all over the world) have seen Audubon art reproductions, whether they realize it or not. The prints are framed on the walls of waiting rooms and dining rooms and office hallways. They adorn the walls in the backgrounds of movie sets. They’re copied on tea towels and T-shirts and place mats. In the public domain for more than a century, the more popular ones have been reproduced and sold countless times.

Most people, even if they have stopped to look closely at these prints, aren’t aware of one essential point about them: these are not exact copies of the originals. When Audubon was launching his Birds of America, no technology existed for making a direct reproduction of a painting. Every method available involved some intermediate step to produce something that could be printed.

Even where Audubon’s original was complete, Havell sometimes made improvements.

Copper-plate engraving was the option considered state-of-the-art at that time. A skilled engraver would copy the details of the painting onto a thin sheet of copper, cutting fine lines and tiny pits into the metal. Ink applied to the copper plate would settle in the engraved spots, and that design in ink could be transferred to a sheet of paper. The resulting print, black lines and dots on white paper, could then be colored in by hand to approximate the look of the original.

Alexander Wilson, preparing his American Ornithology, had experimented with engraving his own copper plates in 1805. After assessing his less-than-stellar results, though, he had opted for having the work done by a professional: another Scottish immigrant, Alexander Lawson, Philadelphia’s leading engraver during that period. Audubon apparently never even considered doing his own engraving. He had his hands full with trying to find as many bird species as possible and with producing hundreds of paintings; the essential task of engraving could be left to a specialist in that craft.

Mountain Plover by John James Audubon. In this composition, Audubon painted only the bird, and the entire background was supplied by his engraver, Robert Havell Jr. This was true for many of the plates in The Birds of America, especially toward the latter stages of the project, as Audubon came to rely more and more on Havell’s artistic skills.

Mountain Plover by John James Audubon. In this composition, Audubon painted only the bird, and the entire background was supplied by his engraver, Robert Havell Jr. This was true for many of the plates in The Birds of America, especially toward the latter stages of the project, as Audubon came to rely more and more on Havell’s artistic skills.

When Lawson and other engravers turned him down in the United States, it seemed a setback. But being forced to travel to England turned out to be a stroke of great luck. Audubon’s rough clothing and mannerisms had marked him as a country rube in Philadelphia. In England they were even more out of place, but they made him interesting, an exotic character. He took advantage of it, leaning into the persona of the American Woodsman, turning himself into a selling point for his drawings. (He would become a master of public relations. In later years, when he headed off to a remote area like Labrador or the Missouri River, he would arrange for friends to send letters about his exploits to the newspapers to keep him in the public eye—essentially sending out press releases.)

Going overseas also gave him a reset as a bird expert. Friends and fans of Wilson in America were already suspicious of Audubon’s claims, but British naturalists, dazzled by his artwork, saw no reason to doubt him. He was soon accepted and honored by scientific societies there, making it possible eventually for him to gain such honors in America as well.

Most important, though, in England he wound up working with Robert Havell Jr. of London, one of the most highly skilled engravers in the world at that time. Havell was a brilliant artist in his own right, and his masterful engravings added to the quality of the published plates.

Once they established their working relationship, Audubon often relied on Havell to finish details of the compositions—or more than details. His original watercolor of the Mountain Plover showed just the bird on plain paper, with a trace of shadow under its feet. Havell added an entire mountainous landscape behind it. Similar collaborations, with Havell providing everything but the birds, produced several of the other color plates. Often these were of western birds that Audubon had never seen in life, drawn based on specimens provided by others, such as the California Quail, Black Oystercatcher, Steller’s Eider, and Marbled Murrelet—as if he were less personally invested in these.

Even where Audubon’s original was complete, Havell sometimes made improvements. His treatments of water in the background, such as reflections and details of waves, are often much better than in the originals.

I’m inclined to think that Audubon, if he had been placed in the same situation, would have done the same thing.

However, even when the engraving hews closely to every original detail, differences in the resulting prints will be visible. Almost all the original watercolors for The Birds of America have been preserved: the New-York Historical Society bought them from the artist’s widow in 1863. Images from the collection can be viewed on the Society’s website, and they have been reproduced directly in book form in a couple of different editions. It’s possible now for anyone to make comparisons between the works as they came from the artist’s own hand and the much-better-known prints based on Havell’s engravings.

Viewed closely enough, differences are apparent. In the prints, but not in the originals, narrow black outlines around objects usually can be seen. In the prints, subtle shading from light to dark is accomplished in a variety of ways, and with considerable skill, because Havell was a master of the technique called aquatint as well as regular engraving, etching, and drypoint; but even the smoothest gradation may show a mottled or stippled effect that differs from the appearance of the original watercolor. Large areas of plain color, such as blue skies or open waters, often look more even and smooth in the prints than in the originals.

When I first began working on my own pseudo-Audubons, trying to imagine how John James would have painted the birds he missed, I had to confront a decision: Should I seek to emulate the style of his originals, or of his universally known prints? The question would make only a small difference in the early stages of each drawing, but a bigger difference in how I finalized them.

In the end, I opted for a sort of compromise, a hybrid approach. I figured it gave me something of a hedge against criticism. If someone looked closely and said that my narrow dark outlines around objects were unrealistic, I could respond that such outlines were features of the engraved prints. If someone complained that part of a background was incomplete, I could claim that this was the way it was done in the original watercolors, and the engraver’s colorists would fill it in. It was a cop-out—and I’m inclined to think that Audubon, if he had been placed in the same situation, would have done the same thing.

__________________________________

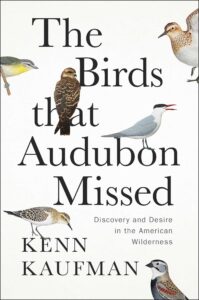

From The Birds That Audubon Missed: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness by Kenn Kaufman. Copyright © 2024. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Kenn Kaufman

An avid naturalist since the age of six, Kenn Kaufman burst onto the national birding scene as a teenager in the 1970s, hitchhiking all over North America in pursuit of all the bird species he could find—an adventure chronicled in his cult-classic book Kingbird Highway. After several years as a professional tour leader, taking birding groups to all seven continents, he transitioned to a career as a writer, illustrator, and editor. He is among the youngest persons ever to receive the highest honor of the American Birding Association—and the only person to receive it twice. He has authored or coauthored thirteen books about birds and nature, including his own series of Kaufman Field Guides. Since the 1980s, he has been an editor and consultant on birds for the National Audubon Society, and he’s been a Fellow of the American Ornithological Society since 2013. Kenn lives in Oak Harbor, Ohio, with his wife, Kimberly Kaufman, who is also a dedicated naturalist and the director of a local bird observatory.